How long must a movie run to convey the full depths of its characters’ regret? For director Ryusuke Hamaguchi, it must run three hours. One minute short of that, if you’re splitting hairs. While that may seem like a daunting task for anyone considering Drive My Car, it helps to know that the depiction of regret becomes increasingly profound and moving, in a way only spending time with those characters can accomplish. That’s especially the case given that the movie isn’t even obviously about regret for much of those three hours.

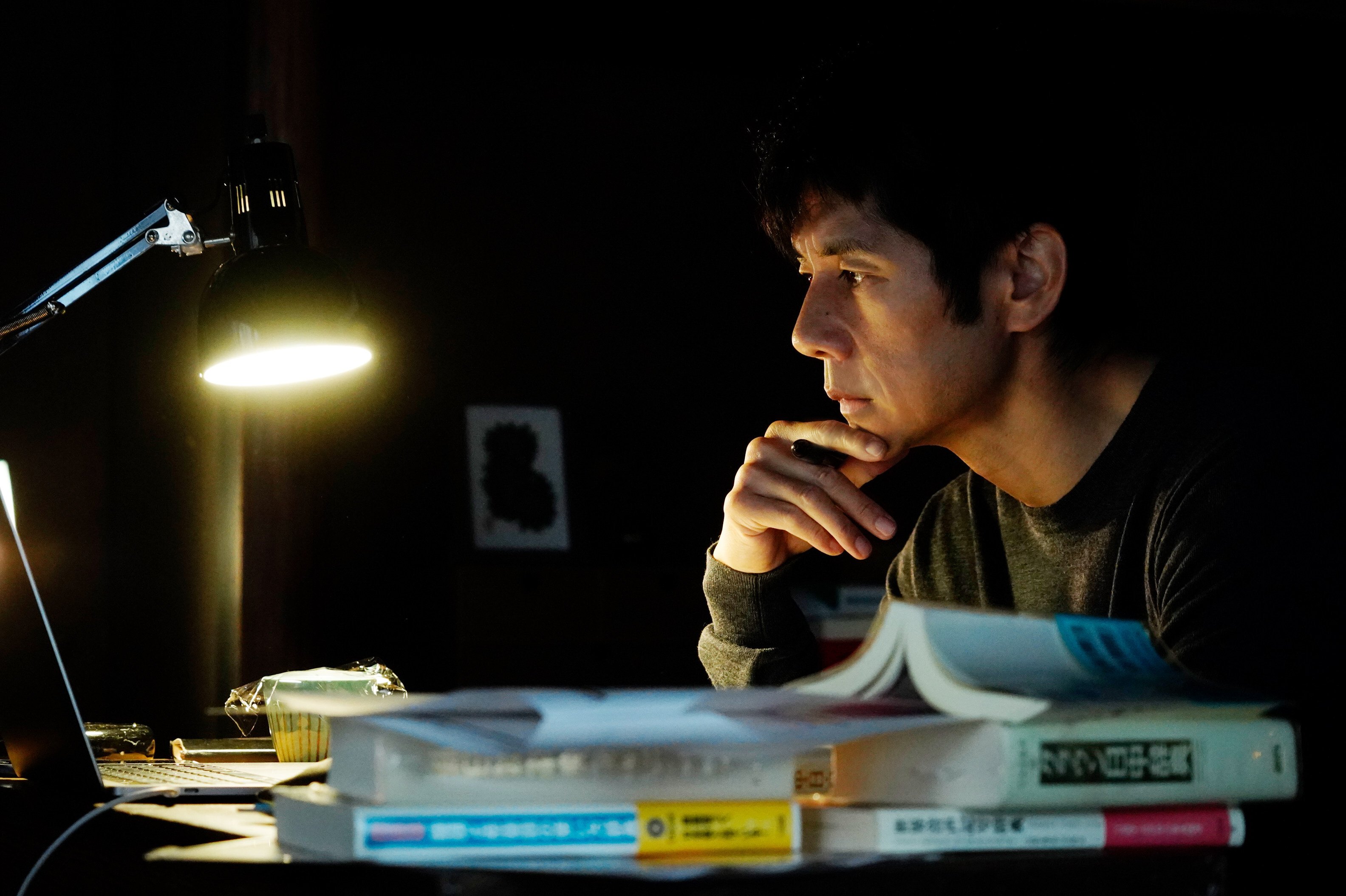

Hamaguchi’s adaptation of the Haruki Murakami short story opens on a scene of two lovers – a husband and a wife, we will soon learn – in bed, languishing in post-coital repose. Instead of the soft words of infatuation of new lovers, or maybe the logistics-laden small talk of a married couple, the woman (Reika Kirishima) tells the man (Hidetoshi Nishijima) a story.

It’s a story she appears to be making up on the spot about a teenage girl who sneaks into the bedroom of her crush when he’s not there. She both takes and leaves small tokens – whose absence or presence he would probably not detect – to mark that she’s been there. It’s clear Yusuke Kafuku is invited to add on to his wife Oto’s story, as though they are involved in a form of mutual improvisation. That’s a natural sort of collaboration given their two careers, she a screenwriter and he an actor/director, both of which involve understanding the motivations of human beings and the intuitive narrative offshoots of their behaviour.

They are also sort of talking in a code. Neither will admit there could be any autobiographical component to this story, which is easy to avoid since it’s heavily shrouded in metaphor. But it’s there unspoken in their words, even though their words are not the least big antagonistic; in fact, quite the contrary. It’s just one of a handful of conversations in this film with a rich subtext the speakers don’t need to explicate.

Where the story goes after this memorable opening is worth preserving as a secret, because there are narrative “surprises” that come both early and late. One such surprise, which indicates exactly what kind of film you’re watching, is that the opening credits don’t roll until the 45-minute mark. Instead of inclining viewers to make that into a joke about how long the movie is, the late credits serve as a line of demarcation between the film’s first third and its final two-thirds. At this point focus shifts to Kafuku’s work adapting and directing Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya, using a cast of different actors from around Asia speaking their own languages, including sign language. A screen above the stage will translate for the audience.

You don’t have to be conversant in any of the languages spoken in Drive My Car, just the language of cinema. That phrase “language of cinema” is not to be taken cheaply, as in camera or editing tricks designed to show off the technical mastery of the one performing the tricks. The cinematic language in question is the one that pays the audience the ultimate compliment of understanding what’s really going on in a scene without one character having to explain it. At any point where a lesser screenwriter might drop in a line of dialogue to clear up the ambiguity, Hamaguchi lives in the ambiguity. He knows that a pregnant pause, a meaningful look from one of his exceptional actors, speaks volumes.

Communication is a core element of this story, though characters are rarely communicating the way one might expect – or sometimes communicating at all, until the flood gates open as the narrative progresses. Kafuku’s driver, to whom the film’s titular command is implicitly spoken, is an example of the latter. A tough young adult whose job is to drive the director from his hotel to the Uncle Vanya rehearsal space, Misaki (Toko Miura) initially seems like an impenetrable shield that will neither emit inner light, nor permit outer light to get in. She isn’t going to stay this quiet the whole movie, though.

The theme of communication is further explored through the staging of the play itself. Those more familiar with Uncle Vanya than this critic might get even more out of that theme, but it rings loudly for the uninitiated as well. It is indeed an experimental method by which Kafuku casts his plays with actors who don’t speak the same language – we see another example in his staging of Waiting for Godot – and the explanation could be as simple as not wanting to exclude the best performers based solely on the inconvenience of their native tongue. One wouldn’t do such a thing, though, if it weren’t to examine the notion that all art is a way of breaking down barriers to communication between people with incompatible backgrounds. It’s certainly an acknowledgement by Hamaguchi that his film will and should be seen by an international audience, prepared to find universal truths within the specific context he’s presenting.

And what an international reception it’s gotten. Just this week, Drive My Car made it not only to the final five Oscar nominees for best international film, but the five nominees for best director, and the ten nominees for best picture – rarefied air for any foreign language film, particularly films originating in Asia. Just two years ago, Parasite became only the first foreign language film ever to take down the best picture award, and it too hails from Asia. Maybe, when you also factor in the success of Netflix’s Squid Game, audiences are no longer viewing subtitles as a detriment to their possible enjoyment.

Kafuku knew they would work for his Uncle Vanya audience, and Hamaguchi made a similar gamble. Not specifically with his language, maybe – no one would expect you to make a film in any other language than your native one – but definitely with his running time. When the observations about the human condition run this deep, no amount of them feels like too much.

Drive My Car opens today in cinemas.