Battlefield Earth.

The most baffling component of faith may be the disunion that belief can have with the beliefs of others. Is one religion more valid than another? Is religion less valid than atheism? The actions of the subjects of Alex Gibney’s Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief may appear bewildering to the uninitiated but it’s worth considering just how confronting it can be to try to comprehend convictions that differ from one’s own.

There isn’t much that’s particularly revelatory in Going Clear regarding the ideology of Scientology. Gibney’s film, based on Lawrence Wright’s book of the same name, is more clarifying overview than damning investigation. From an outside perspective, regarding Scientology as exceptionally outlandish isn’t a stretch. It’s no secret that Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard once commented that starting a religion would have enormous financial benefits or that the fundamentals of the Scientology philosophies share a striking kinship with Hubbard’s early science fiction literature. Other information, such as scandals regarding prolific Scientology members or abuse of power within the system, are hardly new but it’s certainly illuminating within the context of all the rest of it.

The insight that Gibney offers into Hubbard is fascinating and even if half of what Going Clear presents about the man is true then many of Hubbard’s actions and convictions were questionable. But for all of Hubbard’s calculation and deceit – and he is presented by Gibney as a particularly unappealing shyster – it’s David Miscavige, the current Chairman of the Board, that comes across as the figure who has been monumental in steering Scientology toward the position it maintains in the world today.

The key interviewees are the most compelling elements of Going Clear, particularly Mike Rinder, Marty Rathbun and Tom De Vocht; ex-members of the Church of Scientology who effectively comprised much of Miscavige’s inner circle before defecting towards the end of last decade. They share damning stories about the man himself, his astonishing abuse of power and his callous manipulation of devout Scientologists in the name of financial and institutional longevity. It’s one thing to hear stories about Scientology through rumour. It’s another to hear them directly from precisely the personalities who would know the truth.

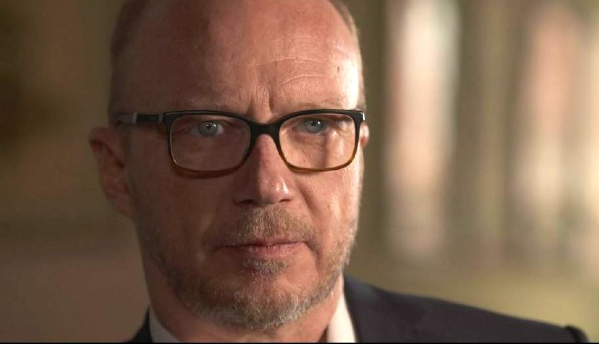

What sort of personality type joins an organisation such as Scientology, if indeed there are prevailing traits? Early on in the film, Wright explains that the intention of his book was to explore how Scientology draws minds in and retains their devotion. Gibney’s film touches on this but not enough to comprehensively convey how someone like screenwriter Paul Haggis, now so vehemently opposed to the organisation in which he involved himself for over thirty years, could have such a change of heart or why he was so drawn to Scientology in the first place. There’s some detail about the way in which Miscavige encourages intimidation and blackmail, among other methods, to foster membership but there’s a rational disconnection between some of the interviewees with their former behaviour.

There’s nothing transparent about Gibney’s regard for Scientology. Going Clear presents the organisation as a cult and the head figures as morally corrupt and abusively manipulative. The effect is chilling but there’s an opportunity missed to rationalise the appeal in Scientology, or indeed faith on a broader scale. Khalil Gibran once suggested, “Faith is an oasis in the heart which will never be reached by the caravan of thinking.” There may be no explanation or rationale.

8/10

For more Reviews, click here. If you’re digging ReelGood, sign up to our mailing list for exclusive content, early reviews and chances to win big!