Run.

Can a film be judged within the context of the series to which it belongs, or should it be solely judged on its own merits? Surely the very nature of a sequel invites comparison? Indeed, comparison is an asset to an episodic saga because it delineates progression. Colin Trevorrow’s Jurassic World is part of the greater Jurassic Park cinematic world, conceived for the screen by Steven Spielberg over twenty years ago; the original film an adaptation of the Michael Crichton novel of the same name. As a custodian of the ‘Jurassic’ title, Treverrow’s film unquestionably warrants scrutiny regarding its benefit to that saga.

The benefit is little; perhaps even none. The original Jurassic Park was Spielberg’s answer to the imprint that Cooper and Schoedsack left on the world in 1933 when RKO released their film King Kong. From enormous, tribal gates to colossal monsters to the concept of man pushing their actions beyond their means to the sheer impossibility of the visual spectacle, Spielberg’s film, wittingly or not, shares an enormous kinship with Cooper and Schoedsack’s. There was such a sense of wonder and excitement to Jurassic Park, as there must have been when King Kong was released. In this latest instalment, by comparison, things happen. And then other things happen. And so on and so forth.

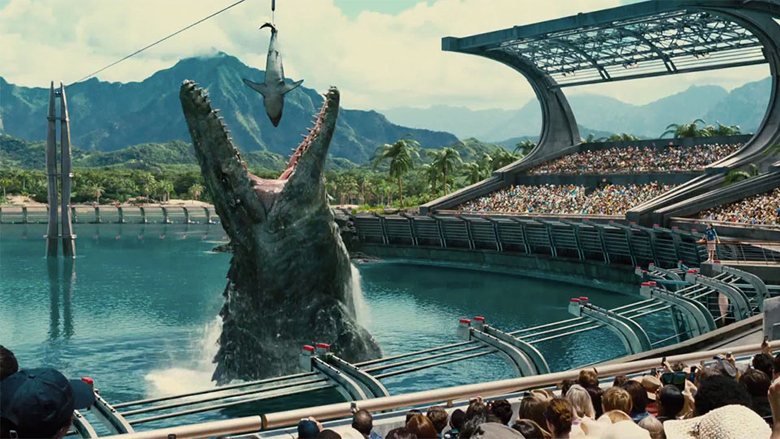

Dinosaurs were amazing in 1993, but they’re not anymore. That’s a concern voiced by Claire Dearing (Bryce Dallas Howard). She’s talking about the dwindling attendance of Jurassic World, the culmination of John Hammond’s dreams – a theme park where everyone can witness his miracle of forced evolution. Unbeknownst to Dearing, she’s struck a concerning chord regarding the nature of the very film that she inhabits. Dinosaurs were amazing in 1993, but they’re not anymore. In 1993, computer generated images weren’t the crutch they are in filmmaking today. Notable instances of the tool before Jurassic Park was released, including The Abyss, Young Indiana Jones and Terminator 2, are so as a result of their rarity.

Spielberg was the first filmmaker to employ CGI on such an enormous scale. His hesitance with the means forced him to use it wisely and, crucially, creatively. The consequence has had a paralysing influence on imagination in large-scale film production. Dinosaurs aren’t amazing anymore. They’re not real, and we know it. The irony seems to have been lost on Trevorrow, who answers the dilemma of wonder by flooding his film with excessive computer imagery in place of thoughtful visual construction and fabricating a dinosaur in place of the series’ staple threats. Narrative, characters and thoughtful filmmaking perhaps ought to have been his concern instead.

Jurassic World is fully operational and under the supervision of Dearing, who is the park operations manager. Fuelled by anxiety that the appeal of the park has lost its modernity, Dearing and her supervisors authorise the creation of the world’s first genetically conceived dinosaur, the ominously titled Indominus Rex. There’s also Owen (Chris Pratt), a former Navy SEAL with ambiguous skills that enable him to train velociraptors. Not train, he corrects us. It’s a relationship of mutual respect. The way in which Jurassic World handles the velociraptors, previously one of the series’ most compelling villains, is a particularly uninspiring development amidst a whirlwind of creative depression, and entirely negates the predatory aura surrounding the species that Spielberg cultivated so well. Last and probably least, Vic Hoskins (Vincent D’Onofrio) is the head of InGen (the company that funds the operation) security and has motivations of particularly ambiguous nefariousness. He seems pleased when people start to die and offers vague suggestions regarding using dinosaurs for military warfare. With scripts like these, who needs enemies?

Treverrow’s inadequacies regarding narrative pacing, establishing atmosphere and hitting character beats are all the more glaring because his work here draws those inevitable comparisons to Spielberg at almost the height of his talent. There’s been a trend of excessive Spielberg exaltation amongst prominent Hollywood filmmakers of late, from J.J. Abrams’ Super 8 to Brad Bird’s Tomorrowland and now Treverrow’s Jurassic World. Embracing Spielberg’s work is one thing but emulating his style is counterproductive.

There’s a moment towards the conclusion of the film in which two of the series’ more popular species share a moment that wouldn’t be out of place in a Lethal Weapon or Die Hard film, which is just as odd as it sounds. “I’m too old for this shit,” the raptor might as well quip. Jurassic Park never needed a sequel. Let’s hope it doesn’t get a fourth. “Yeah, yeah, but your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn’t stop to think if they should.” It’s a bit like that, isn’t it.

1/10

Side note – Does anyone reading this review have their aunt’s contact details in their phone under “Aunt *name*”?

For more Reviews, click here. If you’re digging ReelGood, sign up to our mailing list for exclusive content, early reviews and chances to win big!