The goal of greater representation in film is not always to make us more conscious of racial inequalities, but sometimes, to relieve us of the need of thinking about them at all. Netflix’s Malcolm & Marie might be such a film where the race of the characters was besides the point, except that it brings up the topic itself. Malcolm (John David Washington) is a director returning to his Malibu home after the premiere of his first film that’s gotten warmly received, yet he can’t enjoy the moment because he’s fixated on how white critics will drape a racial narrative over his story of a drug addict trying to get clean. He’s frustrated that this is a reality for Black filmmakers. Even if he wanted to just “go make a Lego movie,” it would be interpreted as a metaphor for the failures of Reconstruction.

Malcolm & Marie is about the furthest thing from a Lego movie, and the fact that it features two people having an argument between 1 and 4 a.m. might not even be the biggest difference. Sam Levinson’s film is shot in black and white, no Lego colour bursts anywhere to be seen. It’s an artistic choice that may have no greater raison d’etre than the beautiful cinematography of Marcell Rev, but Levinson’s film virtually dares us to read a racial undertone into the colour palette, or lack thereof. Over the course of 100+ minutes, though, the film tries to parse out how even matters of black vs. white are not black and white, plus many other things not related to race at all.

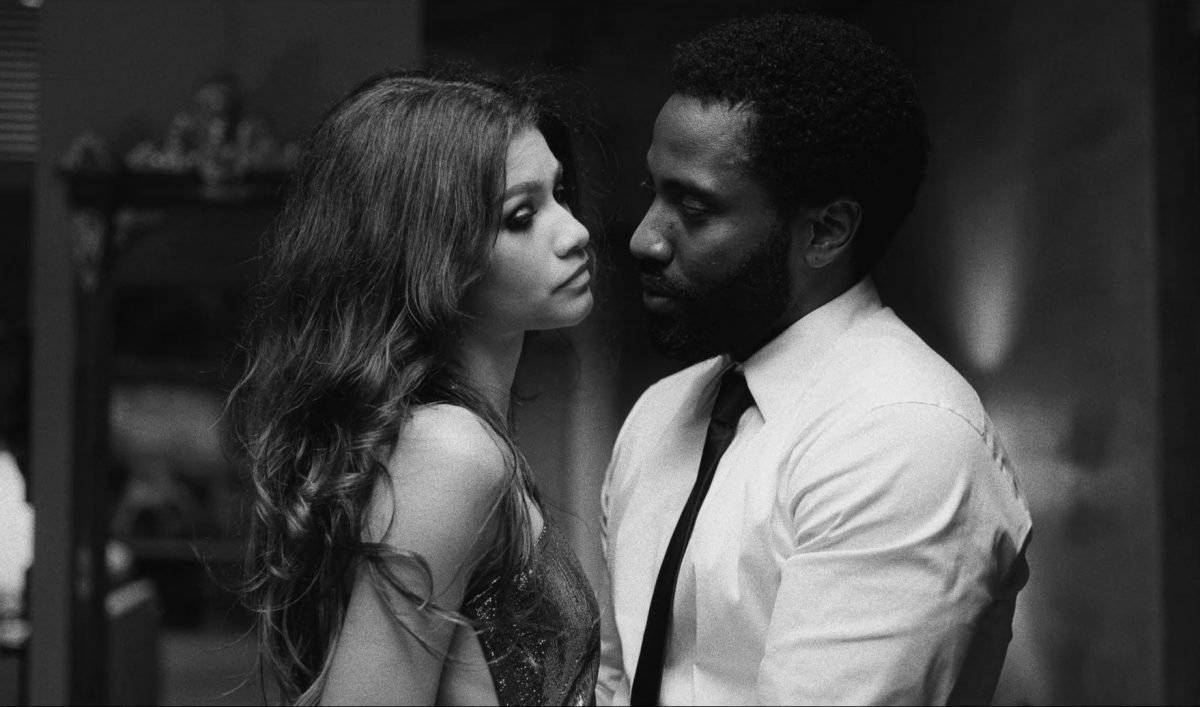

Malcolm’s sparring partner for this extended fracas is, you guessed it, Marie, his girlfriend, played by Zendaya. She’s said and done all the right things at Malcolm’s premiere – and certainly looked the part in a tight-fitting dress – but secretly she’s been simmering all night. You see, Malcolm forgot to mention her among the “112 people” he thanked in the speech he gave before the movie, even though they’ve been together five years, she’s read countless drafts of his script, and she’s contributed things to the film that aren’t revealed until the night gets deeper and darker. He immediately realised the omission and continued apologising throughout the movie. She accepted the apologies to keep the peace, but now that they’re home, the gloves are coming off.

If Malcolm had just kept the post-party smile on his face, or if he’d been sated by the pot of macaroni and cheese she makes him, or even if they’d just gone to bed, Marie’s simmering might have gone unnoticed. But he starts off on a harangue about the Los Angeles Times critic who spoke to him afterward and called him the next “Spike Lee, Barry Jenkins or John Singleton” – three successful Black directors. Malcolm wonders why she couldn’t have compared him to William Wyler, the director of such classics as Roman Holiday and Ben-Hur, and when Malcolm gets a good rant going, there’s no stopping him. At this elevated intensity level, he finally starts asking about Marie’s monosyllabic responses, and this is when the evening turns fractious.

Malcom & Marie dares critics to be offended by what Malcolm thinks of them, but that would be a shallow reaction. This is not Chef, the movie Jon Favreau made when he was angry over the reviews for Cowboys & Aliens, which turned the movie into a nakedly artistic outlet for his axe to grind. For one, there’s every reason to believe we’re supposed to take a lot of what Malcolm says as bullshit. Although he hits on a dozen valid points in any of his several rants, particularly the ways white critics perform wokeness for their reading audience, his words are tainted by his own self-aggrandisement, not to mention a terminal blindness in the way he misuses Marie. (Though as we find out, she’s no mere victim either.)

Then there’s also the issue that Malcolm & Marie may not actually be an example of the thing it is purportedly talking about, a Black film twisting critics into knots to fit it into a larger sociopolitical context. Its stars may be African-American, but its writer-director is white. At a time of peak interest in the notion of who gets to tell whose story, Malcolm & Marie dives right into controversy by putting a white-written script in Black characters’ mouths. It’s as though Levinson is simultaneously fanning the flames and trying to douse them with the film’s own internal arguments, which also get at the collaborative nature of film, and who is actually the storyteller of any given story. I suppose he’s damned if he does or if he doesn’t, as the film is significantly more familiar, less interesting and less contemporary if it were just a two-hander between privileged white people. There can’t help but seem something flagrant, though, about his disregard for the way his words could be interpreted as a sort of cultural appropriation.

The kind of discussions Malcom & Marie engenders are probably good ones, and the way the performers command them verge on great. Tenet’s complicated mechanics may have squelched some of Washington’s natural charisma, but it comes storming back here. Denzel’s son continues to resemble his dad in his capacity to perform verbal theatrics, and he’s got ample opportunity to strut his stuff here. He can also tone it down to add enormous depth to pregnant silences and can push single tears down cheeks in a way his previous work may not have demonstrated. Zendaya has much more of a low-register history, and especially fulfils that role next to Washington’s histrionics. But she’s capable of mixing it up in ways probably not seen on film, though she did just earn an Emmy for her TV work in Euphoria, where she has also worked with Levinson. She’s powerful here.

Fortunately, this is not just a movie about Black directors in a white world. The bulk of their drawn-out tete-a-tete delves into their histories, together and apart, the times they supported each other and the times they failed to do so, their strengths and their major character flaws. Eighty to 90 minutes of this might have played a bit more strongly than 106, as the discussion inevitably has to become more peaceful and playful just to ease the tension and to give us a little break, before veering back into more dangerous emotional territory with little fresh provocation.

This format, though, does have a distinguished history on the silver screen, a fact that matters to a film so interested in that history. It’s reminiscent of the the epic drunken sparring between Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, even though there were technically two other characters present in that one. That the parts are essayed here by two actors of colour, at the top of their games, is certainly progress, no matter who is delivering it and with what legitimate authority.