Miles to go.

One way to avoid the cradle-to-grave trappings of the typical biopic is to pretend your subject is not actually dead. Just before the end credits of Miles Ahead, a graphic comes on screen showing Miles Davis’ birth date (May 26, 1926), a dash … and then no death date. The words September 28, 1991 should have followed that dash, but Don Cheadle’s film asks us to think of the jazz great as immortal, still with us in spirit and musical legacy if not in body. While that’s a nice sentiment, it doesn’t fully excuse the shabby, shambling 100 minutes that have preceded it. The film tries to glean emotional honesty from a dishonesty of fact that’s more harmful than a simple omission of a death date, and it only succeeds in fits.

It’s fair game to play with the truth a bit in a biopic, for any number of reasons – maybe you need to combine two characters to streamline the narrative, or speculate what happened in a conversation where no witnesses were present. But what Cheadle has done in Miles Ahead crosses over to an irresponsible level of fiction. The film’s entire present tense is an imagined (i.e. fake) interlude in which Davis (Cheadle) is being hounded by the Rolling Stone reporter (Ewan McGregor) who wants to write the story of his comeback after five years of self-imposed isolation. Davis conscripts “Dave Braden” (not a real person) into helping him score cocaine and try to recover the tape of the stolen studio sessions that are key to the proposed comeback. These things did not actually happen, but they comprise a good 60 percent of the film’s running time. It may not be irresponsible to Davis’ legacy, as his family signed off on Cheadle’s vision for the movie, but it feels irresponsible to those who want to know about real things the real Davis really did.

Oh, those are there in the flashbacks, which are intercut with these flights of fancy and contain more readily verifiable information. These scenes are as regrettably familiar to us as the other scenes, by their artificial nature, are necessarily unfamiliar. Cheadle lays Davis’ spiral into drug use and creative despondency at the feet of a lost love, as many of these flashbacks involve him pining for the dancer ( Emayatzy Corinealdi) he married and then abused. Such cause-and-effect suppositions, accurate though they may be, have a tendency to over-simplify the psychology of the person in question. As they are a real crutch in biopics, their inclusion here just reminds us how little Cheadle’s film is actually overcoming the limitations of his genre.

So Cheadle can’t really win here. When he’s doing something outlandish, it’s too much, but when he’s doing something safer, it’s too conventional. Where he should be rewarded is his attempt to give us a glimpse of Miles Davis at all. As jazz is an increasingly less known form among today’s young people, one of its all-time legends also remains a mystery to them. While Miles Ahead keeps a lot of that shroud in place – which is exactly as the man, who cherished his privacy, would have wanted it – it does find some emotional truth in among all the “lies.” And that can be credited to Cheadle, who has been working on this as a passion project for some time, and didn’t even originally intend to play the role himself. One never doubts his commitment to delivering something Davis would have felt fairly represented him, as the text frequently references his intense feelings of ownership over his own creative output. He didn’t fully succeed in distilling Davis, as the scenes showing the germ of his genius feel obligatory and rushed. But a personality does emerge, so we come to understand the why if not entirely the how.

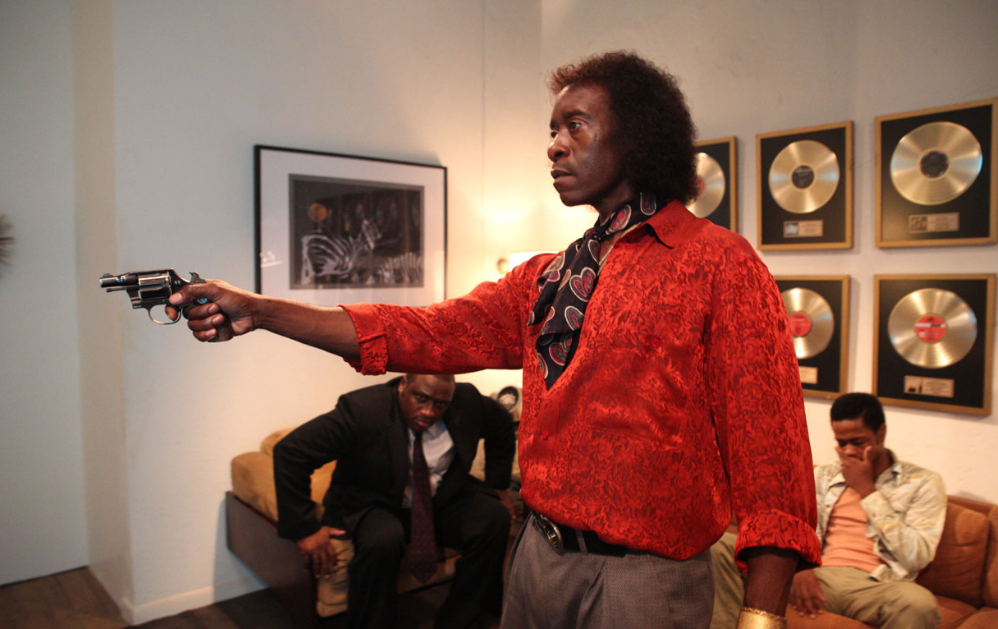

The present tense stuff – occurring around 1980, it would seem – might have worked better as well if it weren’t so fixated on entertaining us. The movie takes on the dimensions of a buddy comedy, with Cheadle and McGregor driving around New York and cracking wise while stumbling into hijinks involving pistols. The cracked out genius wielding a gun made its appearance as recently as 2014 in the James Brown biopic Get on Up, so that particular bit feels especially reheated. Then Miles Ahead sometimes even resembles an action movie, as there are – yes – car chases and shootouts. Given that everyone involved basically worships Davis, even those the screenplay designates as adversaries, it seems unlikely that any of them would risk shooting him.

Technically the film is hit and miss. In his first effort as director, Cheadle is definitely interested in flashing some clever camera tricks, smash cuts, cutting on form, and other film school visual flourishes. Some of them mark him as more of a novice than if he had just taken a more straightforward approach, but others are suitably lively and do make the movie more watchable. The overall look is a bit grainy and faded, perhaps a byproduct of the film’s budgetary limitations (Miles Ahead actually received some crowd funding through Indiegogo).

It’s ultimately unclear whether those young kids ignorant of jazz will actually be served by this movie. In the end, it lacks the grandeur that someone of Davis’ stature deserves, and therefore fails at elevating him to timeless status. Or maybe it’s just that it takes a cinematic genius to truly convey the genius of another artist. For all the things he does well, Cheadle isn’t there yet, and may never get there. Not everyone can be a genius, you know.

5/10

For more Reviews, click here. If you’re digging ReelGood, sign up to our mailing list for exclusive content, early reviews and chances to win big!