The spirit of Jazz.

“Humans are imperfect. That’s one of the reasons that classical and jazz are in trouble. We’re on the quest for the perfect performance and every note has to be right. Man, every note is not right in life.” – Branford Marsalis

There’s a dinner scene, around halfway through Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash, in which the central character’s pursuit of distinction in drumming is unreasonably, and also unwittingly, dismissed by his family. They feign support, and probably genuinely believe that they are being supportive, but their obvious enthusiasm for the achievements of other family members – including a teacher of the year, a head of the model U.N. and a first string on the football team – exposes the underlining prejudice in the room against art as anything other than amusement.

One character offers the maddening suggestion that art and music appreciation is subjective, which to artists can sound the same as suggesting that their vocation is essentially meaningless. The protagonist objects and he is absolutely right to do so. There is, without question, an element of subjectivity in the appraisal of a work of art. , For anybody with a reasonable comprehension of an art form, however, objectivity is not some arrogant and philosophically groundless conceit but rather the fundamental tool for appreciating that art form. There are good and bad paintings, there are good and bad films and, of course, there are good and bad musicians.

Chazelle’s film doesn’t explore the difference between good and bad, but rather the difference between good and great. It is a film that understands the sacrifice of greatness and the potential for effort and pain to add up to nothing. There’s an element of suffering to every passion and an awareness in any person at the top of their game that suffering must either be overcome or accepted. Ironically, Whiplash deals with the pleasure being drained from music, a part of life that is ostensibly driven wholly by the pursuit of pleasure. There are no doubt thousands of wonderful musicians who gain nothing but joy from playing, but there are also those who suffer for their art. Whiplash reminds us of the incident in which renowned drummer Jo Jones threw a cymbal at Charlie Parker’s head, in contempt of the saxophonist messing up in a jam session.

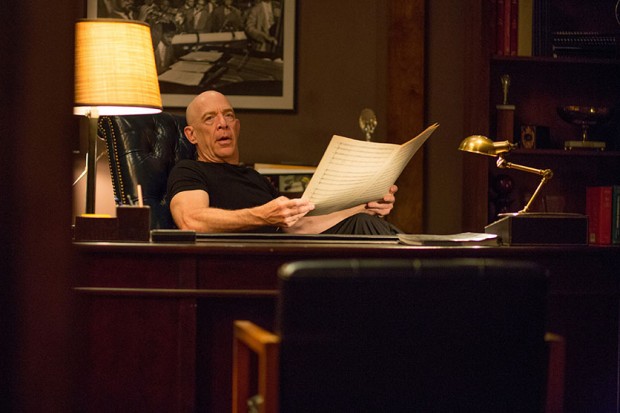

Andrew (Miles Teller) is a young drummer with talent enrolled at the prestigious, and fictional, Schaffer Music Academy in New York. During an afternoon of solitary practice, Andrew is discovered by Terence Fletcher (J.K. Simmons), the band leader of Schaffer’s most esteemed ensemble. Taken aback by the man’s dismissive demeanour, Andrew is surprised when he is eventually offered a seat in Fletcher’s band. On his first day, however, Andrew discovers that his new bandleader’s obsession with perfection is brutal and aggressively maniacal. Fletcher is the kind of man who implies condescension at his most pleasant and employs violence at his least.

Some of the best cinematic villains have an uncanny way of garnering audience understanding despite their deplorable conduct. Whiplash doesn’t condone Fletcher’s methods but it doesn’t entirely condemn them either. He is a villain, perhaps to the point of caricature, but Fletcher is not without a coherent objective. He is a man driven by passion but, without the self-awareness to grasp the consequences of his behaviour, his passion manifests itself awfully. It’s Fletcher’s devotion that Andrew recognises and connects with despite being horribly mistreated by the man. Simmons’ command of the character is such that when he eventually justifies his behaviour (“the next Charlie Parker would never be discouraged”), there’s no empathy, but there is understanding.

Director Damien Chazelle balances the pressured blend of passion, obsession and extremity with cunning, clearly recognising the natural wonder of a virtuosic performance. Flashes of brilliance by Andrew offset Fletcher’s brutality, so much so that if Fletcher were just slightly more forgiving then his behaviour might have been vindicated. Ultimately, however, Fletcher is peddling mistrust and resentment, destroying passion for everyone around him in his blind pursuit of musical legend. He believes in encouraging greatness but there’s no encouragement in his behaviour.

In any pursuit, the more pressure put on someone, the more likely they are to stumble. Whiplash shares much in common with Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan, in the sense that both films consider the relentless pursuit of greatness and the personal cost of achieving it. The provoking thing about Whiplash is that, at its close, you’re not sure that Fletcher is entirely wrong.

8/10

For more Reviews, click here. If you’re digging ReelGood, sign up to our mailing list for exclusive content, early reviews and chances to win big!