Animaster.

‘My old friends and I all refer to Isao Takahata, the director, by the nick-name “Paku-san.” Paku-san’s hobbies are music and studying. He possesses rarely seen and highly sensitive compositional skills, but by nature he is also a real slugabed sloth.’ (Hayao Miyazaki, Starting Point, 201)

The world has been treated to a new English language dub of the Studio Ghibli film Only Yesterday (Omohide poro poro), originally released in 1991. Both the new dub (featuring the voices of Daisy Ridley and Dev Patel) and the original Japanese language version have been playing on Australian screens in select cinemas. Hayao Miyazaki, director of My Neighbour Totoro and Spirited Away, served as a producer on the project. While Miyazaki may be the face and filmmaker we have most come to associate with Ghibli, Only Yesterday is a true example of the best of director Isao Takahata.

It’s little wonder why Miyazaki has become so universally well-known and acclaimed – bringing characters like Totoro and the Catbus to the world, as well as having a reputation for making films featuring independent, spirited female characters. His films are full of wonder, beauty and an almost childlike sense of adventure and hope. But Takahata’s films are something different – his films do not always feel like they have been made specifically with children in mind, as Miyazaki often explicitly states he does. Takahata’s films are equally beautiful and visually stunning, and they can move in distinctive ways. His films are different to Miyazaki’s, but he has been an equally integral part of Studio Ghibli’s history.

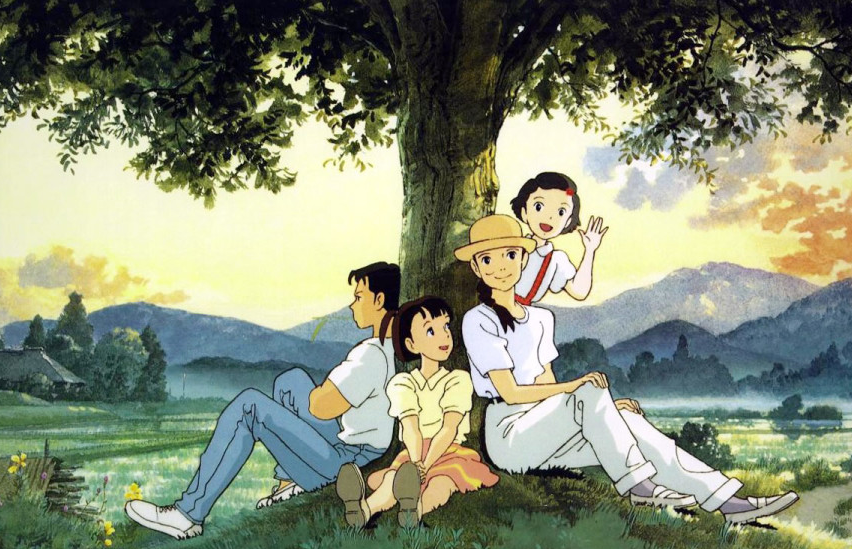

First, a word about Only Yesterday. Based on the manga by Hotaru Okamoto and Yuuko Tone, Takahata’s film tells the story of Taeko, an office worker (and unmarried at twenty-seven), as she travels to the country side for a holiday. Taeko’s idea of a holiday is to work in the fields at her brother-in-law’s farm, amongst the nature and countryside she desperately craved to visit as a child. As she travels and works, she reminisces about her childhood growing up in Tokyo during the 1960s, and in particular the year she was in the fifth grade. Reflection, memory, and a certain kind of melancholic nostalgia are at play in Only Yesterday – the film is a beautiful contemplative work on the significance of life’s myriad events.

Miyazaki declared “The moment I ran across the story of Only Yesterday I knew instinctively that Paku-san was the only person who could properly turn it into a film.” In “Starting Point”, a collection of personal essays, Miyazaki reflects on the making of the film from his point of view as producer, and how Takahata’s sometimes difficult nature as a filmmaker led to the production process getting out of hand (to say the least):

… a twenty-seven-year-old adult protagonist (not in the original story) soon appeared, and began pontificating about farming problems in Japan and helping out with work in the field – and the film quickly started spiralling out of control … So, in conjunction with the very happy release of this most moving film, keep in mind the highly intense internal struggles that went on in the background and made it all possible.

This kind of behaviour and process – long delays in production, reluctance to start a project, or reluctance to finish – are a regular occurrence with Takahata. His work ethic is often lamented by co-workers in Mami Sunada’s documentary, The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness. That film principally follows Miyazaki, as he completes his final film, The Wind Rises. Takahata is more of an elusive figure – never at the main studio, often spoken of but only ever glimpsed in archive footage. At various points throughout the documentary, Miyazaki praises Takahata’s skill as a director, and at other points declares he has lost all hope for him as a filmmaker. “He’s not even trying to finish,” he says of Takahata’s final work, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. It’s a sentiment echoed by others. When asked at a press conference whether a simultaneous release was planned for the two films, veteran Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki responds, “Once Takahata begins, how should I put this…he’s never delivered a film on time or on budget.” Princess Kaguya went on to be nominated for an Oscar.

Perhaps it is precisely because of these ‘sloth-like tendencies’ that Takahata was the perfect person to bring Only Yesterday to the screen. There’s a sense of perfectionism, or a need for constant reflection and revision – a desire to not be rushed into doing anything, and a slow but steady nature that allows not just Only Yesterday, but all of Takahata’s films to be the rich, detailed, and visually stunning stories that they are.

No two of Takahata’s films are exactly alike – they range over adaptations of European or Western works (such as his TV series Heidi Girl of the Alps or his adaptation of Anne of Green Gables), to drawing inspiration from Japanese folklore, to meditations on contemporary Japanese life, family, and culture (Only Yesterday falls into this later category). Grave of the Fireflies is based on a true story, set during the incendiary bombing of the city of Kobe during WWII. Pom Poko draws upon the folklore surrounding tanuki (a raccoon sub-species found in Japan, and in folklore a group of mischievous shape shifters) to become an environmental fable about the expansion of the human world into nature and the loss of tradition. My Neighbours The Yamadas takes the form of episodic segments to tell the story of a family life in contemporary Japan. Princess Kaguya is a retelling of the folk story of a bamboo cutter finding a princess inside a bamboo stalk. Takahata’s films might be considered slow, but they all place a emphasis on the joy and sorrow that life brings, on memory and reflection, and on the inner lives of his characters that requires a level of reserved, steady pacing.

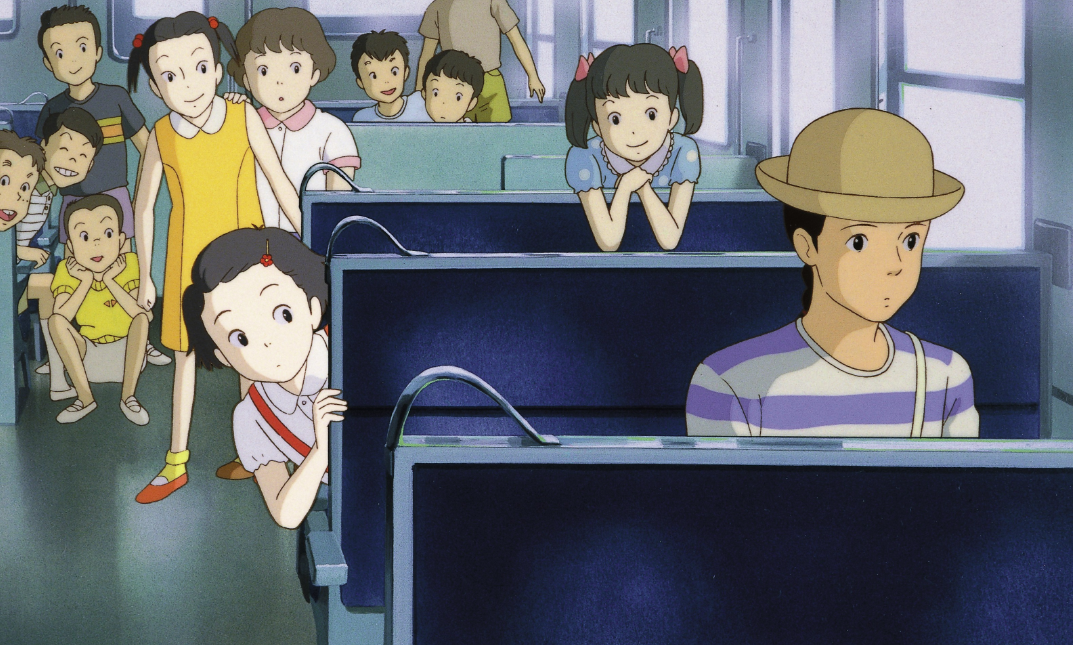

Miyazaki has been highly commended for his heroines, but Takahata’s films are also filled with interesting, complex women of all ages. They may not go on the adventures that Miyazaki’s girls are known for, but they each have their own rich, intricate inner lives and deal with a variety of emotional or personal turmoil. In one memorable scene in Only Yesterda, Taeko remembers the time the fifth grade girls learned about periods, and the mingled feelings of excitement and confusion that swept through the girls at the school. Young Taeko’s initial embarrassment is authentic. The scene is treated as yet another of life’s transitory moments, and whilst it provokes laughter, it is never at the expense of the girls. In Princess Kaguya, Takahata takes a classic folk story and creates an independent, spirited young princess who struggles to reconcile her own desires with the desires of her parents and society’s expectations. The film is tragic and romantic and incredibly heartbreaking, but it is also rewarding.

Miyazaki has been highly commended for his heroines, but Takahata’s films are also filled with interesting, complex women of all ages. They may not go on the adventures that Miyazaki’s girls are known for, but they each have their own rich, intricate inner lives and deal with a variety of emotional or personal turmoil. In one memorable scene in Only Yesterda, Taeko remembers the time the fifth grade girls learned about periods, and the mingled feelings of excitement and confusion that swept through the girls at the school. Young Taeko’s initial embarrassment is authentic. The scene is treated as yet another of life’s transitory moments, and whilst it provokes laughter, it is never at the expense of the girls. In Princess Kaguya, Takahata takes a classic folk story and creates an independent, spirited young princess who struggles to reconcile her own desires with the desires of her parents and society’s expectations. The film is tragic and romantic and incredibly heartbreaking, but it is also rewarding.

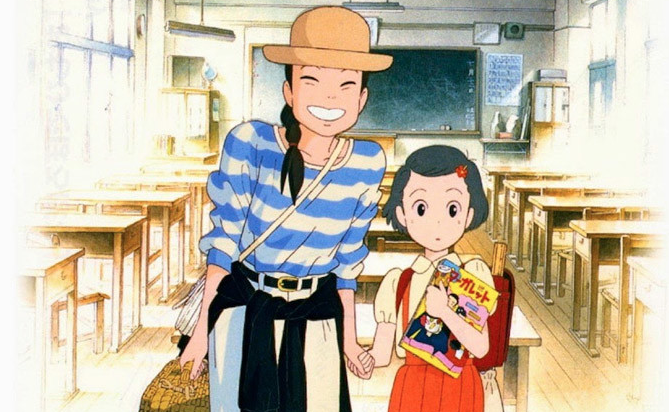

Takahata’s films cover a variety of subject matter and, in his later works especially, he experiments with form and style. In Only Yesterday, as we move backwards and forwards between Taeko’s memories and the present day, the backgrounds and scenery transition from pale and slightly washed out to bold and bright colours. In Pom Poko, the tanuki, who are constantly shape-shifting into different objects or into humans, are at the same time metamorphosing between a more ‘realistic’ drawn depiction, and a cartoonish, exaggerated style of animation. Yamadas and Kaguya are more obvious departures from Takahata’s earlier works, replacing the bold colours and strong backgrounds and characters and instead utilising a soft watercolour or pencil sketch styles that constantly shift and reform as the films unfold.

Takahata once wrote: “It is through Hayao Miyazaki’s very existence that I have always felt scolded for my slothlike tendencies, been made to feel guilty, been cornered into doing work, and had something greater than whatever limited talents I might possess squeezed out of me.” He elaborates further in The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness in the one brief interview he appears in. Without Hayao Miyazaki and producer Toshio Suzuki, he probably wouldn’t be where he is today, but, as Takahata’s producer Yoshiaki Nishimura states, even as he admits to losing sleep over the director’s unwillingness or inability to move forward with his work, without Takahata there would have been no Studio Ghibli.

Takahata is older than Miyazaki. Takahata ‘discovered’ Miyazaki when they both worked together at Toei Animation. Takahata directed, and Miyazaki drew the art. As partners they have split up, declaring they had nothing else to work for together. They are, according to Suzuki, rivals in many ways. They drive each other onwards, and push each other to do better and work harder. Just as My Neighbor Totoro and Grave of the Fireflies were released concurrently in 1988, they were working on their final films at the same time, even though the producer’s predictions came true and Princess Kaguya was not finished on time. Animation fans and enthusiasts in particular will always be quick to recognise and praise Takahata’s skill, but the re-release of Only Yesterday serve to remind that his achievements often fly under the radar outside of Japan when compared with the creative force of Miyazaki’s oeuvre. As the other half of Ghibli’s visionary founding pair, Takahata’s contributions to animation and the Japanese art world should never be underestimated or forgotten.

For more Opinions, click here. If you’re digging ReelGood, sign up to our mailing list for exclusive content, early reviews and chances to win big!