Vincent van Gogh went almost completely unappreciated in his lifetime, so it’s appropriate that a new film about the man would show him only in flashback. Any review of Loving Vincent that starts with a discussion of its narrative approach, though, is truly burying the lede, to use the old journalism term. The form of Loving Vincent is the true headline, as this film allows us to bask in the beauty of 65,000 individually hand-painted frames unfolding before us.

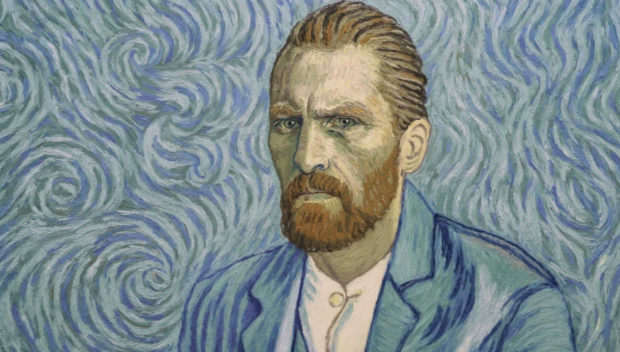

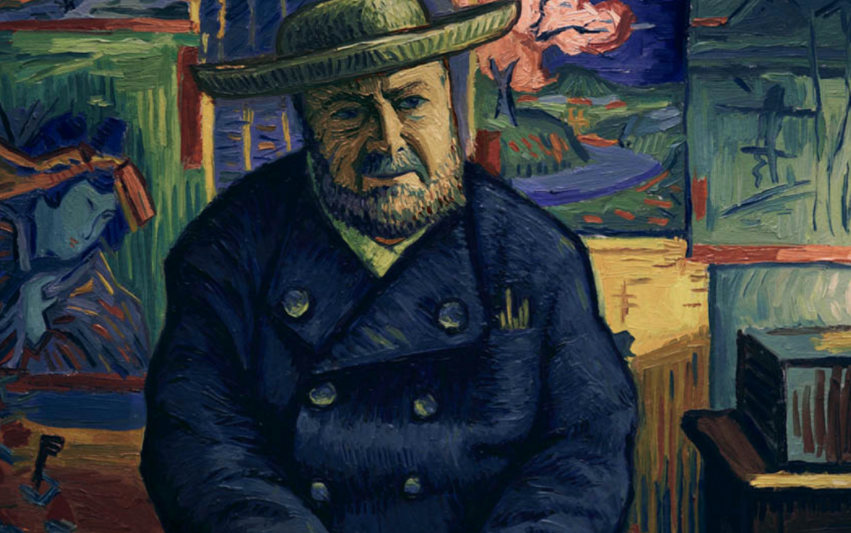

It’s a variation on Richard Linklater’s favoured technique of rotoscoping, which involves the painting over of real images shot by a traditional camera. The look of the film, therefore, is like a van Gogh painting come to life. That its narrative approach also merits discussion is a testament to just what an accomplishment this is.

Directors Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman have constructed their daring technical feat as a Citizen Kane-style series of interviews, where a man named Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth) travels around France meeting with various acquaintances of the deceased artist. This is both to get a better sense of him and to try to deliver a letter to his mourning brother, Theo. Whereas Kane’s central reporter wanted to know what Rosebud meant, Roulin is trying to determine why the troubled artist went from a state of apparent equanimity to death by self-inflicted gunshot wound just six weeks later.

Through these interviews we get recollections of the artist, cobbled together disparately and non-chronologically, based on the nature of the particular interviewees’ interactions with him. A portrait of the man, so to speak, materialises. The flashbacks are in black and white to set them off from the movie’s present tense, which is a year after van Gogh’s 1890 death. Which makes them no less beautiful than the colourful, vibrant, thick brush strokes that more familiarly evoke van Gogh’s work.

The “daring” attributed above to Kobiela and Welchman might more properly be ascribed to the 125 artists who painstakingly painted these frames over the course of seven years. That’s the true labour of love in this project, whose degree of difficulty is a bit like stop-motion animation, but to the nth degree. It’s not necessarily all that different from traditional hand-drawn animation, in that it’s frame-by-frame and features artists all adhering to a distinct animation style. What makes it stand out in the 21st century is that a) pretty much no one does hand-drawn animation anymore, and b) this is not like any hand-drawn animation you’ve ever seen.

The art here is wild and impressionistic in keeping with the style of van Gogh, though not so much that it sacrifices the minute details, at times seeming just like a heightened rendering of the actors and scenery. Indeed, seeing actors like Chris O’Dowd and Saoirse Ronan come to life as oil paintings is a pleasure in its own right. At other times, the images stray a bit from the footage that’s been shot, allowing a headlong dive into van Gogh’s swirling world.

The episodic nature of the work really propels it forward, allowing not only a useful array of perspectives on van Gogh, but also an intriguing and ever-shifting set of theories on why he killed himself – and whether it was even suicide at all. This is a mystery as much as it is a character study. Unless you know the details surrounding Van Gogh’s death intimately, it keeps you guessing.

It’s as much a portrait of an era as it is of a man. So much of what transpires is impacted by the available methods of communication, or lack thereof, at the time. Since this is about real people who lived 125 years ago, it’s no spoiler to say that Vincent’s brother, Theo, died within six months of Vincent’s passing. That’s something Roulin does not even learn until about the third stop of his trip, which makes it problematic indeed that he is trying to deliver an undelivered letter from Vincent to his brother.

Other information and misinformation is spread through gossip, which is the subject of much contempt among some of the characters in this movie – but also a necessary conduit in some respects. Then there’s the notion that some people may be warping the truth for their own gain or to cover for some culpability, in a way that’s worse than gossip. The undelivered letter becomes a metaphor for difficulties in communication in late 19th century France, and also for how much of Vincent’s mind was essentially unknowable.

For something as potentially remote as the life of an artist who’s been dead for more than a century, something that’s literally buried under a layer of technique, the film has surprising emotional heft. Loving Vincent continually reframes our understanding of van Gogh and these characters who could never perfectly express their complicated feelings toward him. Certain revelations, and moments seen again from a different perspective later in the narrative, really pack a punch.

If they did not love him in the romantic sense that he craved (remember, this guy cut off his own ear for a woman), then they loved him for the many talents and eccentric traits the film dramatizes. Vincent van Gogh lived a vigorous life that was also fragile, which he shares with all of us, and which comes out both in his paintings and in this film.