Tyler Perry’s 12 (!) times playing Madea at the movies are like a 17-year sojourn through one artist’s personal schizophrenia. On the one hand, Perry can be a very earnest fellow, inclined to examine serious social issues, especially those that disproportionately affect America’s Black community. That mentality is well represented in his Madea movies. On the other, Perry obviously also likes broad humour involving a gun-toting matriarch prone to mispronouncing words and slapping her family members upside the head, lest he wouldn’t play the role so regularly and with such vigour. These pieces are a sloppy fit at the best of times.

Yet they do sometimes work together in a strange sort of concert. Usually when you get a little Madea and a lot of the social issue, and the social issue is executed with finesse and real insight, you’ve got a film with far more depth than the image of Madea waving around a gun would suggest. You can’t have zero Madea because there are certain audiences who come for the scenes between her and her brother Joe, also played by Perry, just for how deliberately wrong those scenes are. Or rather, you can have zero Madea, but then it’s one of the other films Perry has directed in this fertile 17-year period of his career, not a Madea movie.

It may be a paradox that the best Madea movies are those that feature her only in a glorified cameo, since you wouldn’t expect a character to cameo in a movie whose title bears her name. But the truth is, she’s best used as a spice, not as the meat of the meal. Because if she is the meat, that usually means the social issue is getting the short shrift, and boy does it ever in A Madea Homecoming, Perry’s second Madea movie to be released by Netflix after 2019’s A Madea Family Funeral.

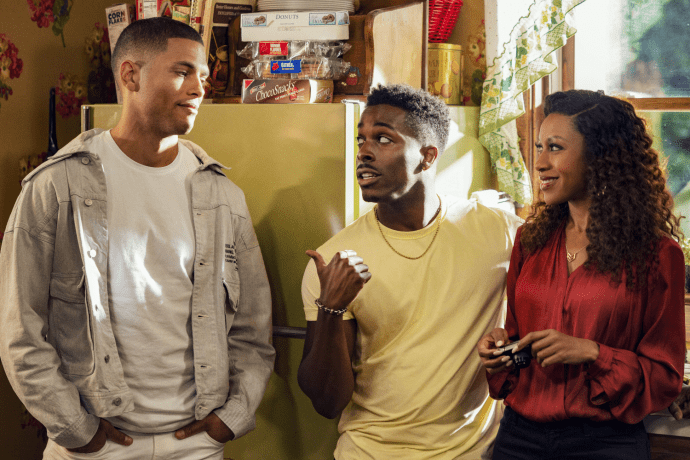

The social issue du jour is homosexuality, specifically, the delayed acceptance of it among America’s Black community. Without diagramming all the extensive familial connections between these recurring characters, let’s just say that one from the youngest generation, Tim (Brandon Black), is traveling home for a BBQ in celebration of his choice as valedictorian of his university class. He’s got with him his friend and roommate Davi (Isha Blaaker), who appears to be more than a friend and roommate. They’re discussing how Tim plans to come out to his extended family, though of course it’s cause for great trepidation, as it still is for closeted gays in any demographic in 2022.

Perry should be commended for attempting to confront his loyal audience with these issues, on which they may not be as enlightened as they think. He should not be commended for his follow-through. Without spoiling some of the melodramatic twists and turns of A Madea Homecoming – they are rightly called melodrama in the classic sense of that word – we can say that Perry whiffs on his chance to show a loving gay couple together on screen. Davi does not turn out to be gay, despite the movie heavily suggesting that he is, though he does turn out to be capable of a frankly rather unlikely betrayal of his friend Tim.

Whether Perry botched a well-meaning impulse or not is sort of beside the point. It’s the percentage of screen time he devotes to it that is the real indicator of the chance this Madea movie has to rise into the top half of the Madea movies or sink to the bottom half. The plot involving Tim’s coming out really peters out and morphs into the thing that Davi does, which doesn’t have anything to do with homosexuality whatsoever – quite the opposite. The petering out is actually a reflection of the characters’ open-mindedness, which is a good thing, but it also reveals a desire to move on to something else.

And that something else is usually more broad Madea scenes. The movie starts with one of the broadest Perry has ever filmed. Leroy Brown (David Mann), a recurring character since the third Madea movie that bears his name (Meet the Browns), is Tim’s father, and he’s preparing the BBQ. Boy is he preparing it. He’s gone through two or three bottles of lighter fluid, then moves on to one of those petrol cannisters with the long nozzles.

It’s meant to establish Leroy as a bit of a jackass, and boy does it do that. However, it’s also meant to establish just how indifferent Madea and Joe are to the suffering of others. When Leroy inevitably goes up in flames, Madea’s very belated response, while muttering under her breath, is to fill a tea cup with water to throw on him. When that predictably has no effect, she half-heartedly tries the hose, whose piddly stream is too paltry to help. Finally Joe trips Leroy so his body contact with the ground will douse the flames, as if that would actually work. It’s a cringey scene from which none of the characters emerges unscathed, though the only scathing to Leroy is that he’s burnt off the seat of his pants.

A drag grandma – though Madea may actually be a great or even great-great grandma – is a problematic character in woke culture. Part of the regrettable history of depictions of Black characters on screen is them repeatedly being asked to ham it up in women’s clothing and the like. Perry seems like the sort who would want to address this in the late year of 2022, but he isn’t doing it in A Madea Homecoming. When a character has been around as many movies and as long as Madea, an ironic sensibility should be creeping in to how she is portrayed, one that addresses these historical shortcomings in representation. The closest this film gets is to make a joke about her age according to one of the stories she tells, which a couple of the younger generation work out to be about 95. Not only is Madea all the other things she is, but she’s also given to telling furphies.

A near afterthought to all this is one other unusual agenda Perry has with this movie, namely, to make it a crossover with the Irish sitcom Mrs. Brown’s Boys (no relation to Leroy Brown, though the joke is made). That also features a drag older woman, the titular Mrs. Brown (creator Brendan O’Carroll), who in the Madea Cinematic Universe is Davi’s family from Ireland. She’s capable of plenty of hijinks herself, including a new addiction to Madea’s pills that get her high, and is the occasion for some decent cultural miscommunications. Whether she is Perry’s attempt to share the troubling aspects of men in drag with another character is unclear.

As long as Perry continues to make Madea movies – and there may not be many more, given that A Madea Family Funeral was once envisioned as the last – they will be worth watching for that instinct to improve the characters and opinions of his audiences via a socially progressive agenda. It’s not promising, however, that Perry refuses to cede centre stage to that agenda. By the time she’s 12 movies in or 95 years old, Madea needn’t be the focus of our attention, no matter how audiences may love her. Even after all this time, Perry still has to learn the difference between spice and meat.

A Madea Homecoming is currently streaming on Netflix.