Disney was once a company synonymous with creation and Walt Disney was a conductor of innovation. He is the man who had originally envisioned a new Fantasia film every year with new animations to different orchestral music. Before that he had established feature length animation as a broadly popular creative platform with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Disney’s creative ambition had a scope that defied genre and convention, as the curious 1946 educational short The Story of Menstruation indicates.

I wonder what Walt Disney would make of the current climate of his company. He is not, as rumours would have you believe, cryogenically frozen, so there’s no way he will ever bear witness to the manner in which Disney is currently evolving the film industry beyond repeal or ruining it beyond repair, depending on who you talk to. What remains undoubtable however is that the titan production company is now a force of recreation more than creation.

This is significant because we are well into an era of blockbuster filmmaking in which an audience can dictate content more than those involved in a film’s production. This is arguably a natural inevitability for a creative medium like filmmaking, which has always been driven by pecuniary matters as a natural consequence of production expenses. Unfortunately, fans do not necessary understand or appreciate what they want.

Consider the most recent Marvel film, Avengers: Endgame. It was a film comprised of a long list of narrative beats that the broad Marvel audience might have wanted to see but void of any sense of the sort of cinematic literacy that begets good filmmaking. Think of the first hour of Jurassic Park and the anticipation and atmosphere Spielberg generated simply because he knew how to command the medium. A general audience may not understand that it is creativity and innovation that established certain films as their favourites and that it is concessions to fan expectations that are diminishing the legacy of those films.

Aladdin is the most recent in an ongoing mission on Disney’s part to remake their most beloved live-action films. These days, blockbuster films are stark reminders more than ever that filmmaking is driven by money. Aladdin is directed by Guy Ritchie. Perhaps he is not the first person you might think of for the job though Ritchie’s exuberance and energy are the most distinct and appealing aspects of this remake.

These Disney remakes are delicate undertakings, a balancing act between being similar enough to the original to satisfy long-term fans while diverging enough to provide a reason for those fans to pay money when they could have just re-watched that 1992 animated version. I would suggest doing the latter as the animated version of Aladdin provides a sense of wonder and excitement that that drastically surpasses this new film while also having far better versions of the songs.

A final note to broadcast the immense talent of Alan Menken. Menken wrote the songs for almost all of the biggest Disney releases during what is now considered the Disney Golden Years, from the late 1980s until the mid to late 1990s. Without Menken, Disney would not have enjoyed the success it did. He returns here, to adapt his old songs and write a new one. I couldn’t help but think that Menken’s instruction on the new song “Speechless”, sung by the Princess Jasmine, was to emulate the style and tone of ‘Let It Go’ from Frozen, which has been an enormous success for Disney. If that’s the case, there may be no more telling summary of where the company’s attitudes lie.

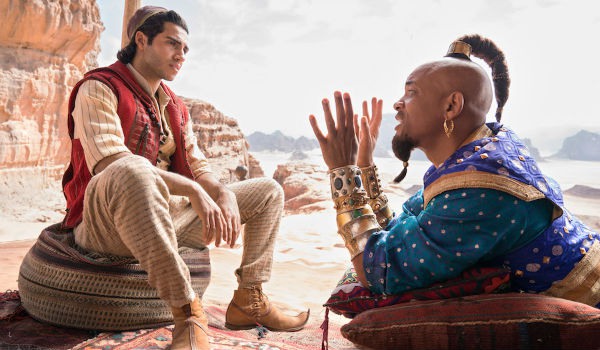

Regardless of whether this is the case or not, Aladdin both represents and feels like a method of maximising profit. The sparks of creativity that slip through the crack are largely thanks to Ritchie, Mena Massoud and Naomi Scott as the charming two romantic leads and Will Smith as the Genie in an unexpectedly successful departure from Robin Williams’ interpretation of the character. This new Aladdin is not without its appeal though its biggest appeal is that it will probably make you want to rewatch the original.