Someone once said that everything that has ever existed is destined to be recreated on film. Okay maybe no one said that, but I’m saying it now. That notion is as much excuse as we need for Rami Malek to give us a killer Freddie Mercury impersonation, and it’s also enough of an excuse for a scintillating restaging of the 1985 Live Aid performance by Mercury’s band, Queen, that everyone remembers. It may also be the only artistic justification for those things, given the comparative mediocrity of the rest of Bohemian Rhapsody.

To be sure, Bryan Singer’s Mercury biopic – from which he was fired near the end of shooting – has aspirations toward a lot more social and cultural relevance. It deals with a flamboyant performer who was one the most prominent AIDS casualties at the time of his death, and who danced around ever fully acknowledging his homosexuality. The movie pays more than lip service to these things, but they are perhaps no more distinct than any of the standard narrative beats of a music biopic. Of which Bohemian Rhapsody includes so many that it almost crosses over into the realm of parody.

Still, there’s a basic jukebox musical-type joy in listening to 15 Queen songs over the course of these 134 minutes, similar to that experienced watching one of this year’s actual jukebox musicals, Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again. Shutting your brain off and enjoying is a perfectly valid response to a movie like Bohemian Rhapsody, when we’re talking about songs that have so embedded themselves in our collective consciousness that they’ve assumed a kind of epic grandeur. And not just the ones that define epic grandeur in and of themselves, like “We Will Rock You” and “We Are the Champions.”

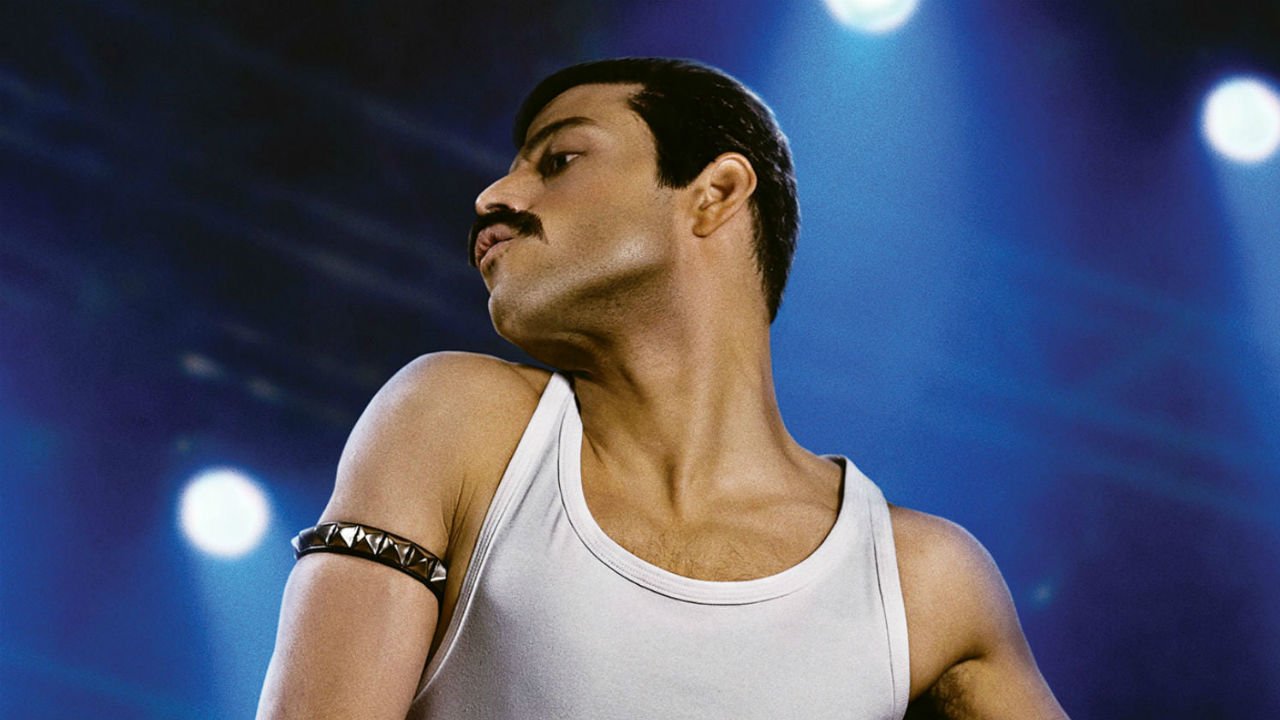

Fans of Sacha Baron Cohen will never get to know what his Freddie Mercury would have looked like, but Malek does a pretty good job distracting them. That is, if you can get past the thing that most distracts from him – a set of prosthetic teeth meant to simulate the four extra incisors with which Mercury was born. In his initial scenes Malek seems to be reckoning with them in a rather awkward way. Whether it’s a matter of him getting used to them, or us getting used to them, they integrate into his performance better as the movie goes along.

It’s the type of movie that invites close readings of its technical details, because its themes are fairly pedestrian. Singer and screenwriter Anthony McCarten opt for a survey approach to the material of Mercury’s life, even though it’s become a more common approach to biopics to focus on a key time period, and then extrapolate a grand unifying theory of that person from there. Either way you are operating within the limitations of the biopic format, which is one reason that genre has fallen on hard times.

Bohemian Rhapsody at least tries to have fun within those limitations, such as the sequence where the band recorded the audacious title song, with its absurdist opera section in the middle, at a farm they were using as a recording studio. The band’s playful shenanigans recall something you might see in A Hard Day’s Night. The film has a cheeky awareness of the importance of this song in the lingering myth of Queen, not only naming the movie after it, but giving essentially a cameo to Mike Myers, the actor most closely associated with the song’s rejuvenation when it appeared in Wayne’s World. Myers, playing a financier with a scraggly beard, even describes the song as “not the kind of song teenagers will bang their heads to” – which is of course exactly what he and Dana Carvey did as Wayne and Garth.

The film dutifully marches through the episodes of Mercury’s life and the highs and lows of the band’s fame, leaving not much of a lingering impression but breezing along at a fairly good clip anyway. Any dithering along the way does feel rewarded by the film’s finale, when the band plays at Bob Geldof’s benefit concert for Ethiopian famine, and a digitally populated Wembley Stadium seems to pulse and pound with every clap and stomp of the band’s 20-minute set. The crowd may be digital but the goosebumps are real.

Bohemian Rhapsody is the kind of movie designed to tick boxes, and it ticks them. That doesn’t make it a great piece of art, and it probably qualifies as something of a disappointment to LQBTQ viewers who would have liked a less superficial foray into the queer issues the film raises. Then again, there were a lot of things about Mercury’s life that he purposefully left at a superficial level. Life was a performance to Mercury, and this film honours that spirit, in ways both satisfying and otherwise.