I took a good friend to see the early screening of David Gordon Green’s Halloween tonight. This friend of mine is an ardent fan of horror films, one of two friends to whom I would always defer in regards to the type of films I often watch through my fingers. He has seen every film in the Halloween franchise, and was telling me about Halloween 3: Season of the Witch, which apparently doesn’t involved the series’ pivotal villain, Michael Myers. He was telling me that Halloween 2 isn’t so bad as all that. There are quite a few Halloween films. David Gordon Green’s Halloween is the eleventh in the franchise.

I have seen John Carpenter’s original Halloween. It is a masterpiece of horror. I hadn’t watched any of its sequels, or any other entries in the series, until tonight. That’s not because of any lack of regard for Carpenter’s 1979 film, rather a serious concern in coping with the stress of horror films. I need to pick my battles. Ultimately, my friend and I appeared to draw similar conclusions with Green’s film.

I mention this because it may help decipher for you whether your interest in Halloween is warranted. Those fundamentally opposed to scary filmmaking obviously need not try this as a first venture into the genre but my friend and I were approaching the new Halloween with distinctly disparate prior experience with the franchise.

Green’s film is not particularly scary, and it ought to be. I found the original Halloween terrifying – vivid memories of driving home from the house of a friend (a different one) late one night with my nerves fraying after watching Carpenter’s film may inhabit me forever. Contrastingly, tonight, my nerves remained largely untested.

So Green’s film, a straight sequel to the original that ignores every other entry into the franchise, too errs from jump scares, by and large. But the film doesn’t have that same command of tension and dread, fundamentally rendering each moment of would-be horror somewhat stagnant and lacking in the flawless terror that characterised the 1979 film.

Here’s something – without the 1979 film to shadow this new Halloween by comparison, Green’s film is perhaps more effective than it initially appears; it is certainly a more interesting film than your typical horror. Though the script is embryonic, suffering from many of the weaknesses and gaps in logic that fail the lesser films of this ilk, the atmospheric direction works to mask other, more pertinent shortcomings.

And compared to those lesser films that I just mentioned, this new Halloween is exceptional. I was happily relieved to endure a horror movie that wasn’t hellbent on startling me in lieu of controlling genuinely frightening ideas. It may be unreasonable to evaluate a film in relation to the films with which it shares a franchise, but Halloween invites those comparisons, and both benefits and suffers for them.

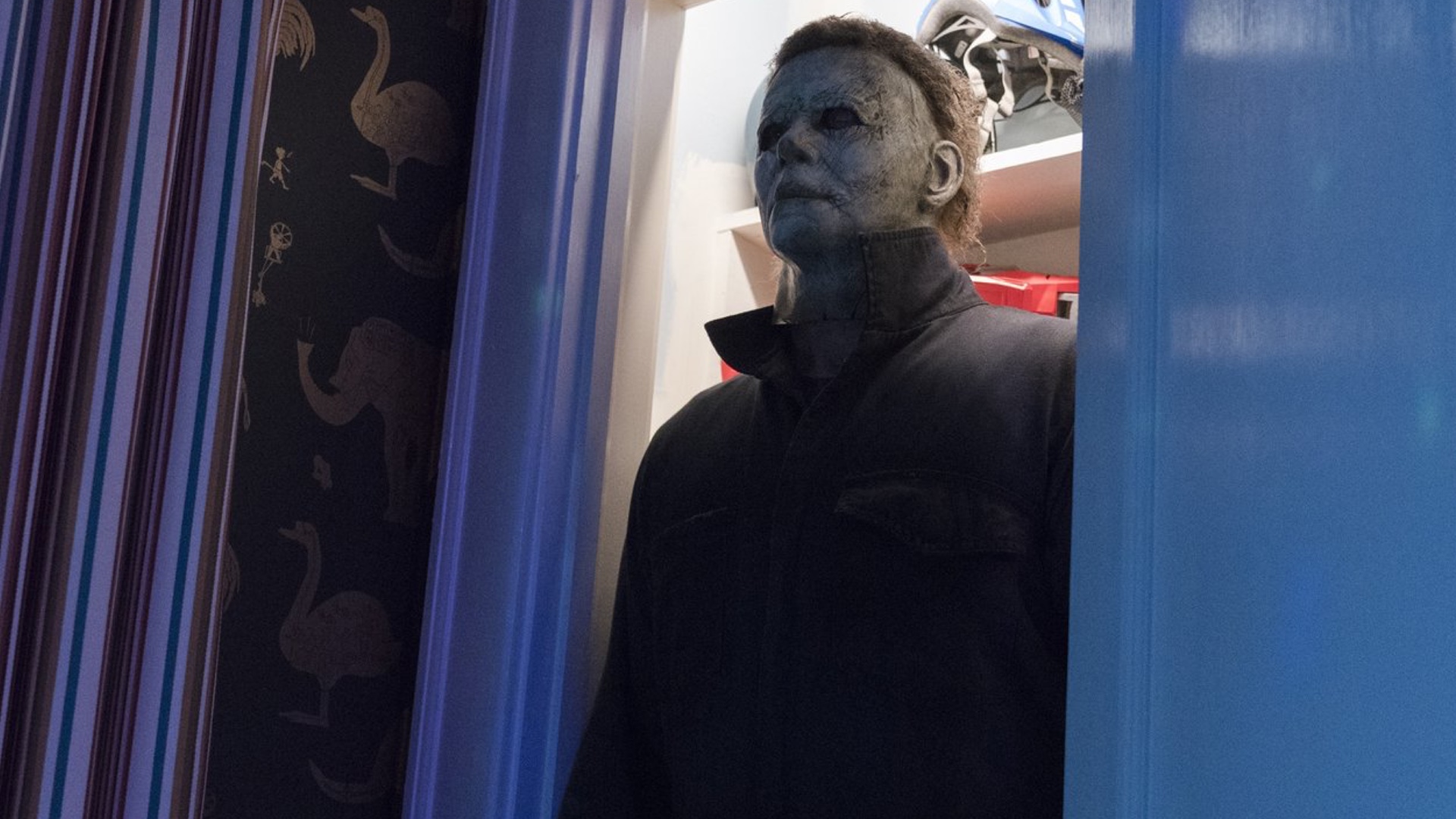

Even without the advantage of its many sequels, the 1979 Halloween established a villain that has and will continue to have an enduring legacy in cinema. Michael Myers is the bogeyman but in the original film he was the bogeyman because his actions conveyed as much. In Green’s film, no matter how many times we are informed just how formidable and evil Myers is, no matter how many victims he kills, that palpable sense of dread that once accompanied him is by some means replaced with unconcern.