Around the midway point of Maestro, a perfectly timed section of dialogue gives voice to something that’s been gathering up in the viewer’s mind. Leonard Bernstein (Bradley Cooper) is talking to a man interviewing him for a book, and he succumbs to some self-doubting despair. “It’s a great source of dissatisfaction that I haven’t created very much at all,” he muses. “When you add it up, it’s not a very long list. I find it very difficult to think that whether I’m a conductor or a composer of any note at all has any bearing on anything. Or that my existence is even worth talking about in this book.”

Amen, brother. Bernstein may indeed be a great 20th century figure. He’s the only lyric that everyone can sing along with in R.E.M.’s “It’s the End of the World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine),” which this movie can’t resist the urge to shoehorn in. But as Maestro quite candidly acknowledges, it cannot make a convincing case for its own existence. It can’t find that thing that makes a two-plus hour movie about Bernstein worth sitting through, not even – perhaps especially not – its naked desire for Academy Awards.

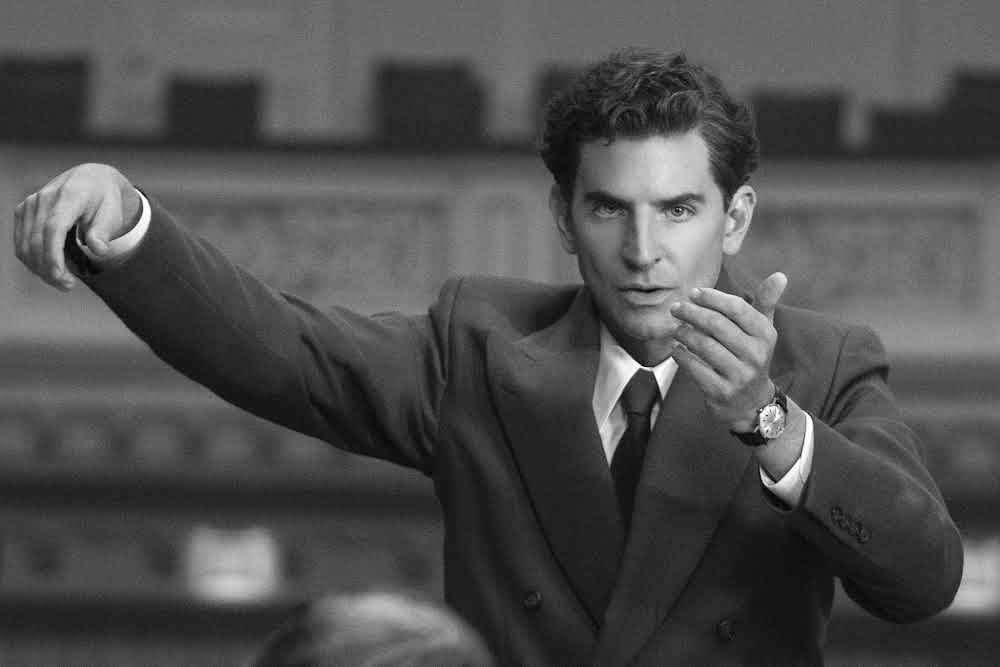

The movie – which was directed, co-written and produced by its star, Bradley Cooper – drops its self-importance on you from the start, beginning in a beautiful black and white that recalls the work of DP Erik Messerschmidt on David Fincher’s Mank. Whatever you thought about Mank, it was clear that the cinematography was a way of shouting its significance from the rooftops. Maestro has its hands cupped around its mouth in a similar fashion, determined to assign importance to Bernstein’s life by hook or by crook.

To be clear, the material is likely there for a Bernstein biopic. For starters, as we learn early on, Bernstein was a closeted bisexual at a time when revealing that would have ended his career before it began. The possibility of discovery did provide tension, not to mention friction in the relationship with his eventual wife, Felicia (Carey Mulligan). In addition to being a world-renowned conductor – an accomplishment somewhat lost on the layperson, who just sees a man vigorously waving a stick in front of the world’s best musicians – Bernstein also composed the score for West Side Story, among other credits.

Maybe a recitation of achievements wouldn’t have been the way to structure Maestro, but at least it would have prevented the film from feeling so aimless. Because the achievements can’t go unmentioned, Cooper and co-writer Josh Singer must give that expository dialogue to some third party, like the interviewer played by Josh Hamilton in that scene where Bernstein expresses his ambivalence about his worth. It’s done awkwardly enough at times that you have to work not to chuckle.

Instead of dramatising the things Bernstein did do, the film mostly focuses on his relationship with Felicia, which was strained by his relationships with other men. Maestro doesn’t do the work to set these up properly, such that we don’t understand the lifelong bond that existed between Bernstein and Felicia, through thick and through thin, nor do we appreciate the competing brands of physical and emotional companionship he received from these men. Nor do we get the sense that Bernstein’s struggles with his sexuality were a driving force behind Cooper making the film. Given the time Maestro doesn’t spend on other things about Bernstein we might find useful, it’s hard to believe it goes so little below the surface on the things it does target. At least through the lens of accomplished DP Matthew Libatique, it’s a pretty surface.

Cooper’s performance is simultaneously one of the best things the film has going for it, and a distraction. Cooper has put himself into different shoes and shown us some range here, but the work ultimately suffers from elements that are both central to his depiction and extra textual. In the former category, Cooper does a lot of “cigarette acting,” in which a cigarette is so regularly clamped between his lips that he seems to be smoking one even when it’s an actual encumbrance to whatever activity the character is supposed to be doing. Such a prop is an old thespian trick that purports to add depth to the portrayal, but can also easily stand out as a crutch. Then there’s the fact that unlike Bernstein, Cooper is not actually Jewish, so they’ve made the choice to enhance the size of his nose through prosthetics. It’s an entirely tone-deaf way to strive for some misguided notion of an unnecessary realism, which would have been hurtful in any context, but especially when the actor is not Jewish himself.

Any individual aspect of Maestro that doesn’t work might have been okay on its own. But when so many don’t work, it’s like a symphony of minor miscalculations, all presided over by a sort of godhead who is doing every job on the film other than best boy and craft services. If Cooper’s role in Maestro functions as a metaphor for the actual job description of a conductor, he’s given us a good example how not to do it.

Maestro is now streaming on Netflix and is still playing in some cinemas.