During a typical moment of introspection in Stutz, Jonah Hill provides the title character, his therapist, the reason he wanted to make this movie: “I wanted to give therapy, and the tools I learned in therapy, to a lot of people through a film.” (It sounds better in the movie, since Hill has his eyes closed, and is completing the thought in sections, broken up by profound pauses.) It’s hard to judge the movie as anything other than a success given this earnest goal, as Hill clearly wants to add to our mental health conversation while sharing some of the benefits his privileged movie star salary has allowed him to purchase over five years of acquaintance with psychiatrist Phil Stutz. (And poor Stutz, I suppose, for severely limiting his number of prospective future patients by giving his methods away for free – or free to anyone who has a Netflix account.)

The movie is not a total success, though, and sometimes feels like it’s well short of that goal. A number of factors prevent it from reaching that level. One is that it feels like a violation of the sanctity of the patient-doctor relationship, even if both participants are willingly surrendering their own privacy. Maybe not the sanctity of the relationship between Stutz and Hill, but between Stutz and his other patients, as he’s implicitly giving away the inner workings of their private sessions as well. Even if Stutz doesn’t care about revealing his secrets, like those guys who tell you how the magic tricks are done, maybe his patients would.

More than the sanctity being violated, it’s the intimacy being poorly translated. The personal revelations that occur to a patient during therapy, encouraged by whatever specific methods the therapist employs, are consummately mind-blowing only to the two directly involved, based on the patient’s personal experiences – and maybe not even mind-blowing to the therapist, who may look at it as just another day in the office. Trying to make those revelations universal inevitably renders them more banal than they are to either Hill or Stutz.

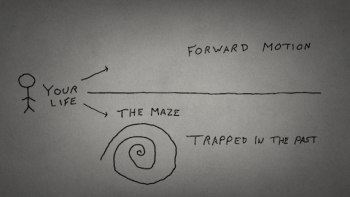

Ostensibly, Hill also wanted to make this documentary because he believes so strongly in the particular methods employed by Stutz. Unlike other therapists, Stutz doesn’t listen and nod and say “That’s all the time we have for today.” Over decades as a therapist – at one point Stutz says he’s 72 years old – Stutz has developed an intricate series of constructs related to examining the human brain and how to unleash its potential. Not its potential to conquer worlds or become captains of industry, mind you, but its potential to live happily and effectively in the world. These constructs are demonstrated visually by scrawling them on the screen in Stutz’s handwriting, then illustrating them with stick figures come to life. They include such personality concepts as “the snapshot,” “the shadow” and “the grateful flow,” though to learn any further about what those mean, you’ll have to watch the movie.

Because Stutz takes such a proactive approach to therapy, giving patients actionable advice as early as their first session with him, his methods could potentially be confused with some sort of Tony Robbins-like life coach, and verge on cultish thinking. To his credit, Stutz never comes off that way. He’s clearly done a lot of thinking about the human mind, but his ideas come off as practical, crystallising common sense notions about how to achieve better mental health, rather than encouraging radical departures from expected paths. Indeed, he does seem like someone it would be great to chat with for an hour, especially since he might do more than half of the chatting. He’s got a wicked sense of humour that plays well off of Hill’s.

Stutz’s ideas could be distilled pretty efficiently over the course of a focused 30 minutes, so Hill still has an hour more to play with. His choices about how to fill that time meander a bit. Even though he claims that this is a movie about Stutz, obviously he’s interested in revealing his own inner psyche, as he’s pressed to share – ostensibly by Stutz, but surely as part of his design for the film – some of his own struggles with body image and the quest for happiness, a quest that even fame and fortune did not help him achieve. Because we know Hill, this material is interesting, though it also seems like Hill is protesting too much that he stumbled into talking about this stuff on camera.

Then there’s the focus on the personal life and history of Stutz himself, including pictures of him and his family in the 1950s through the 1970s. At these points we wonder if it’s sensible to spend quite so much time delving into the personal history of someone who otherwise has no claim to our attention. Sure we watch documentaries about people we’d never heard of all the time, but in most of those cases, the people are culturally or historically significant for one reason or another. Stutz doesn’t fit that bill, though at least he’s interesting.

It was evidently a struggle for Hill to make Stutz, as we learn early on that they’ve actually been filming for more than two years. The film is aware of its own existence from the start, as most documentaries are, but after scarcely 20 minutes, Hill makes the choice to blow up our illusions by revealing that they are not in a real therapist’s office, and that he himself is wearing a wig to resemble his own hair when they started filming. Having destroyed the sense of artifice, he leaves the green screen up as the background for most of the rest of the movie – though it being green is something we have to assume since the movie is mostly black and white in sepia tones. During this segment Hill also confesses that he doesn’t know if this movie was even a good idea.

That this comes so early in the movie strikes us as discordant, and in truth, evidence that Hill’s own doubts about the project might be well founded. This breaking of the fourth wall might have made a better dramatic component two-thirds of the way in, to explode our conception of the type of movie we’ve been watching, and to remind us of the man behind the curtain.

The best excuse for making this movie – and a possible explanation for why Stutz isn’t worried about giving away his secrets for free – is that the man has Parkinson’s. His medicine is controlling his tremor quite well, but at age 72, he’s also past the age many people retire. Either death or retirement will limit the amount of time Stutz still has to commit his concepts to permanence. Hill is indeed doing us a service by putting his methods out there, as a manual people can watch and rewatch if they want to try to insert Stutz’s processes into their own lives. How well he constructs the movie that was designed to do this is open for debate.

Stutz is currently streaming on Netflix.