Most of us heard the 2012 story of Richard III’s body having been discovered under a carpark in Leicester and thought “Wow, really interesting!” Many of us did not take it a step further and figure out how that came to happen. In fact, some of us probably thought they were just digging up the carpark to turn it into something else entirely, and happened across a man with curvature in his spine, who was once the last Plantagenet king of England, buried anonymously under the long since razed Greyfriars church after his death in 1485. What good luck!

There was a lot more to it than that, and Stephen Frears’ new film delves into how that discovery came to happen. The Lost King is a truly delightful portrait of a determined woman named Philippa Langley, played by the truly delightful Sally Hawkins, who developed a fascination with the potentially misunderstood king during a performance of Shakespeare’s Richard III – or so this dramatisation tells it. How much of the film is a dramatisation is being hotly debated, as the villain depicted in the piece – Richard Taylor, one of two prominent Richards involved in the search for the most prominent Richard in British history – has made noises about suing the filmmakers for their uncharitable portrayal of him. It’s actor Lee Inglesby doing that portrayal, but of course it’s really Frears and screenwriters Steve Coogan and Jeff Pope who made the choices.

But movies require heroes and villains, and it’s understood that a fair amount of dramatic license is taken in bringing any historical event to the big screen and giving it a three-act structure with the traditional narrative components. How accurately The Lost King retells the events leading up to Richard’s discovery is already compromised by some moments of light sloppiness on the part of the filmmakers, such as the fact that Langley’s ex-husband (Coogan) and sons go to see the Bond film Skyfall early on in the story – even though it wasn’t released until two months after Richard’s remains were unearthed. Whether The Lost King is true, has the ring of truth or is just a good yarn, it’s affecting as hell.

During the performance of Richard III, Philippa, already feeling like an outcast due to some professional disappointment, experiences a moment of kinship with the actor playing the notorious hunchback, who in the play is accused of ordering the murder of two nephews to remove them from the line of succession. She takes issue with Shakespeare’s assumption that a physical deformity turned Richard into a monster, certainly a fair gripe. Looking into it afterward, Philippa discovers the Richard III Society, which debates the Tudor portrait of the man as a cruel usurper – history being written by the winners and all that. Already persona non grata at work and suffering an illness that leaves her in a fatigued state, Philippa launches the quest to locate Richard’s remains – not that this will actually rehabilitate his reputation in a public fed by “Tudor lies.”

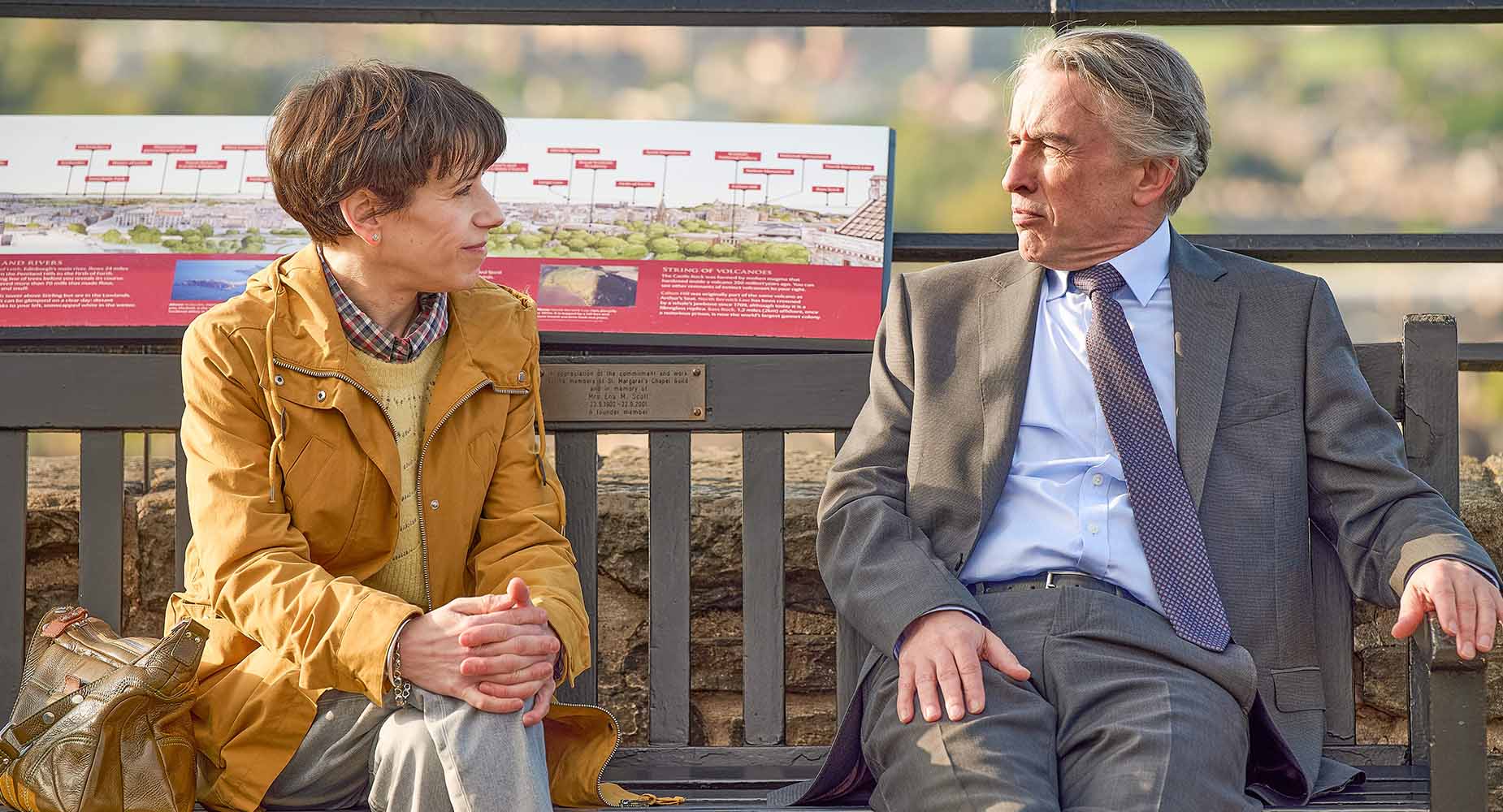

She’s got an unlikely companion in this endeavour: Richard himself. Philippa begins seeing visions of Richard, played by the actor from the stage performance (Harry Lloyd), sitting on park benches or looking up through her window, a Mona Lisa smile permanently affixed to his face. As she develops a friendly rapport with the initially silent king, he becomes the force that drives her onward as she researches and suffers the inevitable disappointments of others’ doubt, as well as the unlikelihood that she will ever amass the funding to perform a dig. She eventually also gets real-world support from her initially sceptical ex, and from a Leicester University archaeologist (Mark Addy), also named Richard, who takes on her quixotic mission more as a reaction to being let go by the university.

Any question of how closely this is meant to resemble reality should be answered by the narrative construct of the ghost king. Surely Philippa Langley did not actually see visions of Richard and imagine herself to be falling for him. However, as these sequences contribute more favourably to her version of the truth than the sexist dismissiveness of Richard Taylor contributes to his, she seems pretty unlikely to sue the filmmakers.

Without her conversations with Richard, though, The Lost King would slip more clearly into the realm of just another recreation of a recent minor historical event, though the discovery of the body of a king probably wouldn’t be considered “minor” in most traditional senses. With that component, it becomes as much an examination of this woman’s soul, which Hawkins is equipped to bear as expressively as any British actress working today. We see how a slew of mid-life crises, including but not limited to her estrangement from her husband, have created unique circumstances where she frees herself to search for personal fulfilment via an adventure no one believes will really succeed. That the estranged husband comes to serve as a sympathetic component of this quest demonstrates the film’s heart and ultimate optimism.

Behind the camera, this is another winning collaboration between Frears, Coogan and Pope, who also brought 2013’s Oscar-nominated Philomena to the screen. Coogan of course starred in that one as well. The tight script and Frears’ veteran direction keep this one moving along at a satisfying clip. Frears has now supported both the Tudors and the Plantagenets on film, having also directed the best picture-nominated The Queen in 2006.

If the real Richard Taylor is to be believed, this is a taking-of-sides sort of film – the Plantagenets against the Tudors, the underdog member of the Richard III Society against a university that belittled and sidelined her, which needed to make him the face of venality and patriarchy. Well Richard, welcome to the movies. While The Lost King surely supports the notion that Richard III was unfairly branded a usurper, on the most basic level, it’s fascinated that what happened in 2012 actually happened – that a random civilian applied the necessary pressure and determination to produce the remains of a world historical figure. If this script had been submitted as a work of fiction, we would have rejected it out of hand. That it really happened is a tribute to everyone involved – even the villains, whether they include any or all of the three Richards.

The Lost King opens in cinemas on Boxing Day.