A lot of great movies derive their appeal from the broadness of their dimensions, their ability to speak to all sorts of viewers in all different contexts. Turning Red, Pixar’s 26th feature, gets its greatness from its incredible specificity – a specificity that gets continually honed into ever more refined levels. Of course that specificity is also in conversation with the more general thoughts and emotions that all people experience, else it would just be somebody’s pet project for them and their friends. But it’s this specificity that disarms and you places you in a state of readiness for what the film has to offer – which is quite a lot.

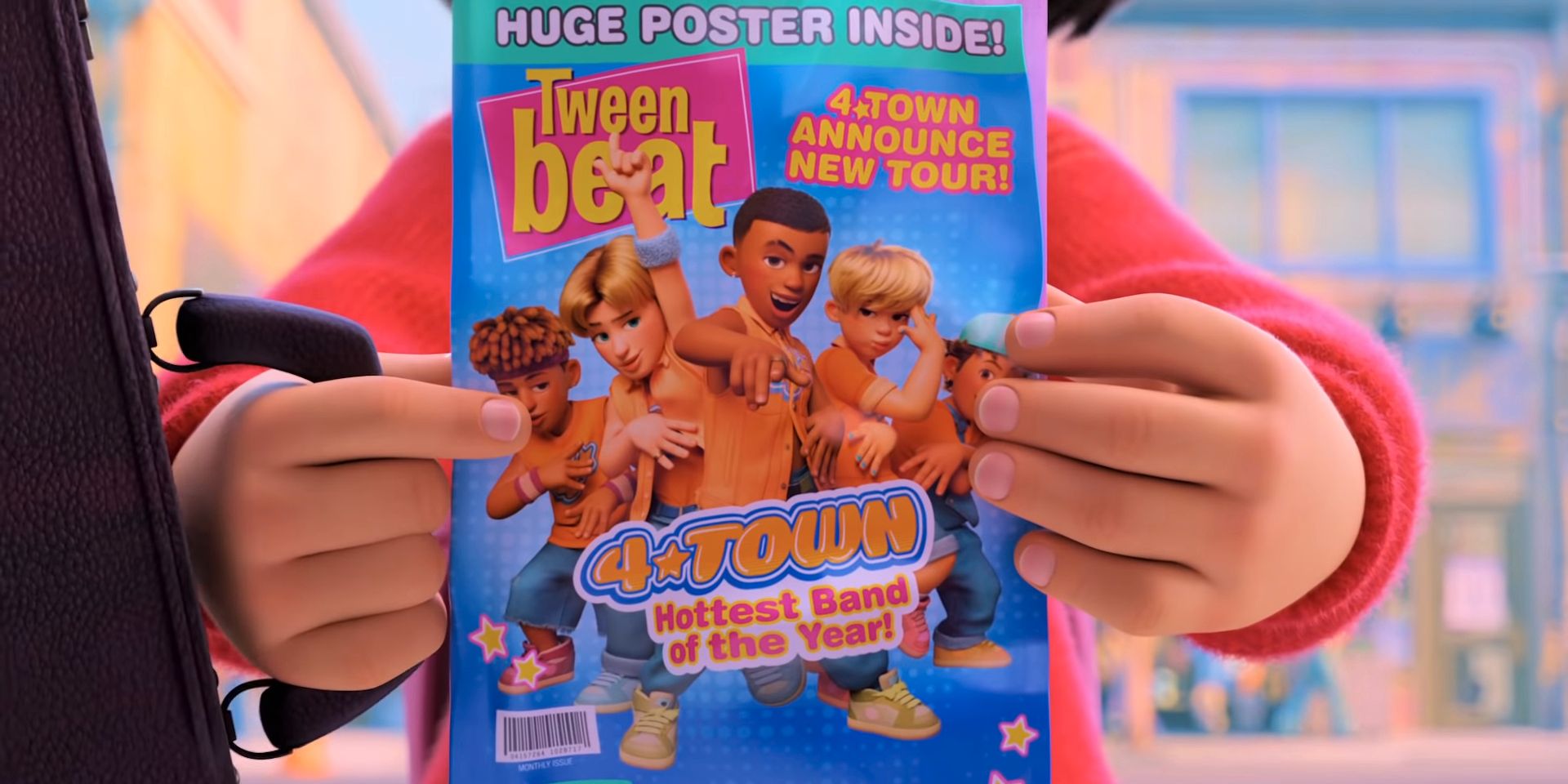

Specific thing #1: The film is a period piece, but from a period that has only just become old enough to seem like a slightly different era. Turning Red takes place in 2002, when boy bands ruled the charts – for the first time since before grunge, anyway – and teenagers were tasked with keeping alive Tamagochis by feeding them at regular intervals. Specific thing #2: Turning Red takes place in Toronto, which is neither the safe zone of a major American city, nor the exotic zone of a foreign locale. Specific thing #3: Turning Red stars a 13-year-old Canadian named Meilin Lee (Rosalie Chiang), who honours her family’s Chinese heritage by keeping up their family-owned temple/tourist attraction, while also honouring her and her friends’ budding libidos as they go gaga for 4*Town, the counterintuitively five-membered band of dreamy pop stars.

Specific thing #4: It’s about young women maturing – both socially, through their interest in boys, and biologically, through the onset of their monthly visitors. One of several controversies radiating out of Turning Red is that when Meilin gets too emotionally stimulated and transforms into a red panda, it is both metaphorically and literally a representation of getting her first period.

Domee Shi, the director of the Pixar short Bao that played before Incredibles 2, must have known the subject matter of her first feature would turn some of its audience red with embarrassment. Also, she must have not cared. It’s a good thing she didn’t, because this wild and woolly coming of age tale is the most free from cinematic forebears of any Pixar release since Inside Out, and finds itself in the vicinity of that film’s effectiveness.

If you must find a film to compare it to, though Turning Red discourages that effort at every turn, how about the Michael J. Fox movie Teen Wolf? There, his transformation into a hairy beast was a metaphor for his character’s onset of puberty, and that’s the same thing going on here – only a lot cuter. Meilin has a particularly active dream one night and wakes up four times her size and ten times her weight, a red panda filling up half her bedroom. She knows the panda is a legendary part of her family lineage, but she didn’t know it was, like, real. Fortunately, this transformation isn’t permanent, though it takes a while to calm herself enough to revert to normal size. This happens just before anyone in her family can see what she’s become – and just after her mother has profferred her a box of tampons, while Meilin shrouds her poofy fur behind a shower curtain.

The brilliant thing about Turning Red, though, is that this is not just another story of a character trying to keep a problematic identity hidden. All sorts of movies have explored the hijinks involved in such an effort, including Pixar’s Luca just last year, in which sea monsters passing as human boys had to guard their secret at the cost of their lives. Turning Red does away with all that, as it soon becomes clear that her family was expecting this change, which affects all the women in their family. Her friends – voiced by Ava Morse, Maitreyi Ramakrishnan and Hyein Park – learn of Meilin’s alternate nature soon enough, and before long, the whole school knows. Instead of ostracising Meilin, this reveal makes her the most sought-after novelty at any party.

The matter-of-fact nature of Meilin’s panda is thematically astute. No young girl can hide her own development into a woman. Rather, it’s what she does with these inevitable changes that provides the meat and potatoes of this film, how she balances them with the responsibility she feels toward remaining the pride and joy of her strict mother (Sandra Oh). The women in her family have been able to suppress their own pandas through a sacred ceremony under the red moon, and wouldn’t you know it, that’s when 4*Town is coming to Toronto.

In being about this very specific corner of the world, Turning Red manages to further Pixar’s worldly agenda. Meilin’s friends include Abby, a boisterous girl of Korean heritage; Priya, a sarcastic girl of Indian descent; and Miriam, a white tomboy, who might be coded as lesbian if she were not equally head over heels for 4*Town. Beyond this, the film explores the straddling-two-worlds nature of Meilin’s existence, equally rooted in her Chinese heritage and her Canadian upbringing, a duality experienced by immigrants the world over. But since this is Canada, known for its niceness, it feels like a welcoming environment for such a melting pot, the story’s only real villain being a spoiled fellow teenage boy, Tyler, whose surname (Nguyen-Baker) signifies his own mixed cultural background. Then you’ve got the director herself, the first woman to get a solo directing credit on a Pixar film, let alone the first woman of Asian descent.

Turning Red also has an evident interest in Japanese culture. This is the Pixar house style for sure, but it isn’t afraid to deviate from that by using exaggerated, expressionistic techniques that recall anime, such as when the girls get stars in their eyes over any boy who tickles their fancy. The transformations into pandas – no, Meilin’s is not the only one we get – is something Hayao Miyazaki might do, and that sort of wonder follows the characters throughout. Shi is taking what we already know of Pixar and delightfully pushing its boundaries to its furthest reaches.

Haters have predictably found toeholds in a story that focuses so much on girls and women, perhaps using the way the film confronts us with the girls’ biological maturation – though never as much as it could – as the excuse they need to launch further salvos at the film. Haters are never the right people to listen to, and that’s especially the case here. Turning Red is a watershed moment for Pixar, relying on none of its previously existing IP, instead using a boundless imagination and knack for symbolism to give us something both thrillingly new and thematically important. We all have a “red panda” inside of us, even those of us not getting our first monthly visitor.

Turning Red is currently streaming on Disney+.