When the director of Unsane unretired from filmmaking last year, Logan Lucky did not seem like the type of movie to entice him back. Pleasurable though it may have been in spots, the film did not challenge the form the way Steven Soderbergh has liked to do whenever he hasn’t been making Ocean’s sequels or other obviously commercial fare. It turns out Soderbergh came back to challenge the norms on distribution – a venture that failed miserably in the short term when Logan Lucky tanked – but one might have expected an outside-the-box approach to the form of that movie as well.

Unsane is more like the type of movie Soderbergh would have come back to make, a clear relative of his experimental films like Bubble and The Girlfriend Experience. It’s shot entirely on an iPhone, a la Sean Baker’s 2015 film Tangerine, and it has a kind of fish eye lens invasive quality that amplifies its themes about mental health. Alas, underneath that technique is a very conventional form of storytelling, replete with the predictable narrative beats of a genre film, which limits the effectiveness of a movie that otherwise has a lot to offer.

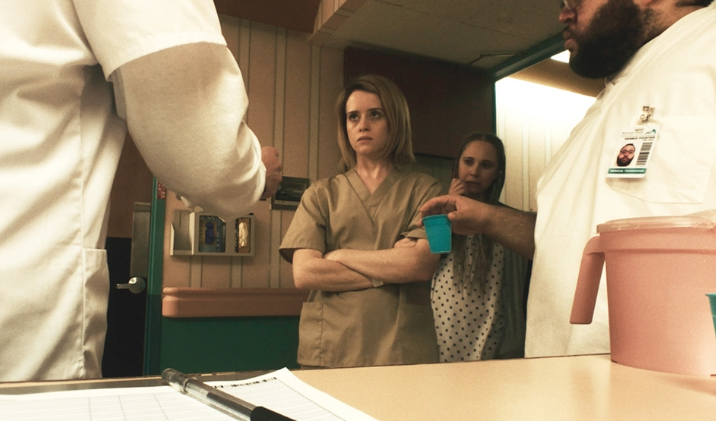

If there’s a single-person incarnation of the best reason to see Unsane, it’s star Claire Foy, not Soderbergh. Foy is familiar to Netflix subscribers as Queen Elizabeth in the first two seasons of The Crown, quite a different role from this (and from her upcoming role as Swedish punk hacker Lisbeth Salander). She’s tasked with playing a bright young financial analyst who has recently wriggled free of a two-year stalking episode, who expresses suicidal thoughts to the wrong therapist and ends up voluntarily committing herself when she does not read the fine print on the form she signs.

The movie then taps into a very legitimate fear of what happens once you get entangled in the mental health apparatus, when the very attempts to prove you’re sane can sometimes end up being interpreted as “what a crazy person would say.” Psychologies are reversed so many times that it can seem hopeless to find your way out of the mess, leaving plenty of leeway for a corrupt institution to bilk your insurance company of all the money it will provide for such a stay.

Sawyer Valentini (great name) shares a certain feistiness of spirit with Queen Elizabeth, but the comparison ends there. We meet her as someone telling off a bank costumer who is unhappy with her analysis of the customer’s loan-worthiness, then sniping at the co-worker who playfully teases her about her manner with the customer. Having been followed for two years by a stalker has clearly taken its toll on her, though we get the sense she wasn’t much of a people person even before that.

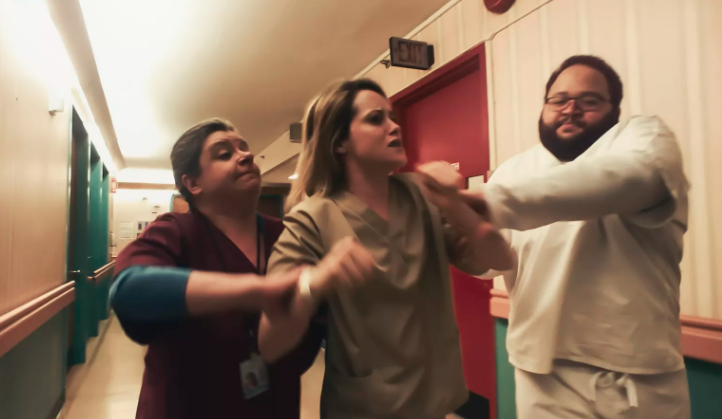

The problem is, once the involuntary “voluntary commitment” has occurred, these personality traits are the sign of a mentally ill person, especially when combined with little bursts of possibly justified violence that she can’t control. Add in your standard post-traumatic delusion or two, and if Sawyer Valentini isn’t careful, she’ll be in here for a long, long time.

Without spoiling the film, suffice it to say that Soderbergh tips his hand pretty early about which one of these things it is, leaving the remainder of the running time a lot less interesting. This results in a disconnect between the engrossing and immediate look of the film and its comparatively pedestrian plot. You might argue that the plot seems more pedestrian as a result of the fact that it’s shot on an iPhone, because there’s eventually a sense that the promise of this new school form is being squandered on an old school narrative trajectory.

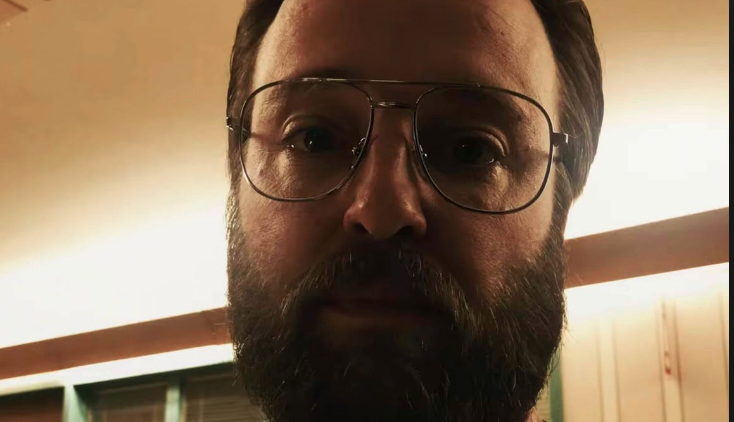

But the film is worth seeing for its look and for the performance of Foy. The iPhone does guide the types of shots that can be rendered effectively, but it’s the placement of the camera that feels inventive. We get a lot of confronting close-ups of Foy and others, which both encapsulate the way she’s feeling boxed in, and also simulate her hen-pecked perspective on what’s happening to her. The film feels claustrophobic in the best possible sense.

The other half of that equation is Foy, who is involved in a constant internal struggle between the emotions she wants to burst out of her, and the consequences of losing that control. The fact that she often doesn’t succeed in controlling herself just intensifies the difficulty for the character, and gives new dimensions to the subtlety of her acting. The Crown was by no means Foy’s first acting role, as she’d been in a handful of other TV series as well as film roles, but the fact that she can do both that show and this movie means that she’s someone we should find compelling to watch for years to come.

Even though this film doesn’t figure to be any more of a success than Logan Lucky – it was very lonely by myself in the cinema, on only its second night of release – it does feel like an instance of Soderbergh coming back to filmmaking for the right reasons, a clear step forward from last year’s redneck heist film. Although it’s tethered to convention in ways that are sometimes disappointing, Unsane represents the type of risk a person can and should take when using new technology and distribution methods. Here’s hoping there will be more of them.