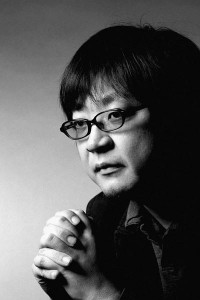

Mamoru Hosoda is the award-winning director of films such as The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (2006) and Summer Wars (2009). He has recently been touring Australia to attend some special Q and A screenings of his latest film, Wolf Children.

Wolf Children is the story of Hana, who meets and falls in love with a man at university. But he has a great secret. He is a Wolf-Man, who can turn into a wolf at any time. They have two children, their daughter Yuki, and son, Ame. The children carry the same ability to transform as their father. When he dies tragically, Hana must raise their children alone.

Hosoda-san has already appeared at Q and A screenings of his latest film in Sydney, and Melbourne, and will also be at Supanova Pop Culture Expo in Brisbane.

Thanks to Madman Entertainment, I was able to sit down with this talented director and ask him a few questions.

First of all, congratulations on the success of Wolf Children. Can you tell us how the idea for this film came to you?

I always wanted to make a film about a mother, or someone bringing up children. And then, my friends who are young mothers bringing up children who were two, three, four years old, I found they often described their children as monsters or animals. This is because the children would often fall over and cry suddenly, and make so much noise, or they would basically totally trash the room, etcetera, and from this I thought it might be interesting if it wasn’t like you were talking about your children as monsters, but maybe if your children were really animals, what would happen? So that was my inspiration for the movie.

Your films before Wolf Children involved more sci-fi type settings, such as time travel and cyber space, but this one feels like it could come from a fairytale or a legend. Did you make a conscious decision after your last film to move towards a more fantasy based setting?

For me, science fiction and fantasy are more or less the same. My interpretation is that sci-fi is something that has a science background or some data to it, so it’s called sci-fi. What’s called fantasy, it doesn’t have a science background, but it might have some historical or traditional sort of thing. So for me, although the three movies may seem dissimilar, they all have the same kind of area, in that I’ve always liked to depict something that is not quite daily-life, and maybe slightly strange.

That is something I’ve noticed while watching your films, is that even though as you say, the settings may be a little dissimilar, you always return to the same themes: people being out of place, facing something out of the ordinary, growing up, coming of age, the theme of family – is this something you consciously try to explore?

I’ve always been interested in the changes or the growth of the characters. For example, like you meet someone and you first don’t think anything about that person and then really fall in love or something, and the opposite of that – you really love someone, but then something happens and you’re totally not interested in that person. Or you think that someone is a child, but then suddenly that person is an adult. Those sorts of changes, and why that happens, and what entails it, those things I’m really interested in, as you said, that’s probably why the all appear in the films.

Even though the title of your latest film is Wolf Children, as you said it really is about their mother Hana and her raising the children. I personally found I could relate to her because she reminded of a lot of women in my family…

You’re right – the title is called Wolf Children, one would think we would mainly be talking about the wolf children, but actually as you say, Hana is the main character. I would like to be slightly proud about that – there aren’t many movies like this, where the main character is not the actual title. I know this because I looked at many films to find something I could use as reference, and I really couldn’t find any. What I wanted to focus on here was, of course we wanted to focus on wolf children we could have focused on the wolf part, but I wanted to focus on how they grew up. We think of parents bringing up children as a natural thing or something that is almost their duty or something anyone does, but I wanted to emphasise that it’s not just a natural thing or something we take for granted, but it’s a conscious, very special thing and that’s something I wanted to focus on.

What I found so special about Hana is that she faced so many challenges she was unprepared for, but she kept pushing though them. She’s another in a strong line of female characters you’ve produced (Makoto in The Girl Who Leapt Through Time; Natsuki and the Grandmother in Summer Wars). Why do these female characters so appeal to you?

I do get a lot of questions like that, like ‘How come most of my characters are quite powerful females?’ and I think I could say that I feel that females have a more interesting life that is more suitable for films, more cinematic. Why I say that is that I feel women have more options – do you marry or not marry? If you marry, do you want to continue work or not? And then you can choose, do you have children or not have children? And then if you have children, whether or not to continue work. With a woman there is many options, whereas with men, I feel that it’s basically you win or you lose. So if you want to make a movie out of a male character, you can only focus on this win or lose story, whereas if you focus on the women, there’s so many more stories. It’s much more complex, rich, there’s so many more options. I think you can come up with many more stories as the number of characters with women.

Wolf Children is beautifully animated, and incredibly realistic. What are your thoughts on hand-drawn animation versus CG?

I really aim to get the feel of hand drawing in this film, but that doesn’t mean that I didn’t use CG – I actually used a lot of CG. For example, there’s a scene where there’s a storm, and the forest and the trees are really swaying, or another scene where there’s a breeze and the flowers are just slightly moving. Those sort of subtle movements, we’ve used a very high level CG to depict that hand-drawn feeling.

In an interview once, in relation to The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, you said that animation is about more than just ‘the power of the image’ and about how images themselves should flow and connect – can you elaborate on that and how would you say this applies to Wolf Children?

In a painting, or something that’s not animation like a still painting, you look at the painting and produce in your mind other images, or thoughts about that painting. The difference between that and animation or a film version, is that with a film you make use of time progress, or the time axis. By using that you can influence the audience. Just because it’s a beautiful scenery, you can’t keep that on forever, that’s not good enough. You can use techniques, such as you can have a certain scenery that might be projected at certain times craftily, and then that will give a different, strong meaning to the audience. You can play with time when it becomes the film or animated version.

I’d just like to give an example with Wolf Children. In the very beginning, there’s a scene where Hana and her husband meet for the first time. The husband was at the bottom of the stairs and Hana was at the top of the stairs. That was how they met, and that’s a very special scene. But much later on, there’s another scene where Yuki, Hana’s daughter, meets her schoolmate Souhei, and it’s in exactly the same kind of setting in the stairs, top and bottom. People in the audience, if they’re clueful enough, they’ll actually remember the first scene, and then the second scene, and they’ll wonder, ‘Why did he use that staircase image once again?’ To evoke those kind of different thoughts, I thought it would be meaningful as well as interesting.

Just finally, I’ve always loved the way your films blend these funny, joyful moments with some very sorrowful, serious moments. Is this part of your philosophy when it comes to making films?

I always want to make a movie that at the end is a feel good movie. But having said that, in real life it’s not all nice things – there are bad things, all sorts of things. But the important thing, what I really like, is the process of where you have hardships, you get over it, and then there’s happy moments and other hardships. I really like to depict that, but at the end, I want to leave the audience with something that makes them feel good.

Madman’s Reel Anime 2013 is coming later this year. If you’re digging ReelGood, sign up to our mailing list for exclusive content, early reviews and chances to win big!