Considering the pre-production difficulties Life of Pi faced, it’s difficult to imagine the film in any hands other than Ang Lee’s. There is an admirable inconsistency to the subjects of Lee’s work. Like Pi, the titular character, Lee is a man who doesn’t accept conditions or boundaries. Equally comfortable with Jane Austen as he is with Marvel Comics, Lee is remarkable in how naturally he allows the story dictate the style, and not the other way around. Few directors are as agreeably chameleon.

Can a film be better than the book it’s based on? It’s an old question amongst cinephiles, and ultimately a subjective one. I believe there are a number of films that are better than the book, although I would have thought Yann Martel’s 2001 novel Life of Pi to be unfilmable. Certainly the directing job is a thankless task; not only was Martel’s book an international bestseller but most of the action takes place on a lifeboat with one human character and an adult Bengal tiger. It’s sort of like Castaway (2000) if the island was two square metres and the volleyball wanted to eat Tom Hanks.

Life of Pi follows Piscine, a young boy from Pondicherry, India, who is named after a French swimming pool and gets teased by other kids at school because it sounds like ‘pissing’. Early on in life, Piscine, or Pi, discovers a powerful connection to God which he explores, to the chagrin of his rationalist father, through a variety of organised religions. The early stages of the film establish a character of deep faith, capable of remarkable hope. In this sense, Pi is unlike many of Lee’s past protagonists. There is a strong sense of emotional isolation to the characters in Lee’s films, a subdued rage towards the restraints of society. Pi is remote, but it is a physical loneliness, not an emotional one. His hope is one of the reasons the film is so watchable.

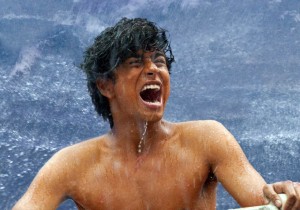

The really amazing thing about Lee’s Life of Pi is that it is successful at all. Much of that is thanks to Suraj Sharma, in his debut role as Pi. Sharma has the difficult task of carrying an entire film with nothing to work with other than a lifeboat and a computer generated tiger. The tiger itself, named Richard Parker, is well handled by the filmmakers and for the most part the CGI is pretty much unnoticeable. A lesser filmmaker may have felt inclined to build a more human connection between Richard Parker and Pi, but Lee keeps reminding us of the dangers of sharing a space with a hungry Bengal tiger.

The film is a fantastic example of storytelling, a mix of survival and wonder. Lee strives to convey a sense of awe, and is mostly succesful. The problem with Computer Generated Images though, is the audience awareness of its artificiality. There are times when it feels as though the the filmmakers are relying too heavily on the power of the images, but it’s a minor complaint in an otherwise exciting adventure. It’s really only in it’s final third that Life of Pi begins to slow down a bit. The ending is weaker than the body of the film, although how do you end a film like this? I couldn’t think of a better alternative.

Although I’m still fairly dubious about the need for 3D in film, Life of Pi makes an admirable case for it. It’s a beautiful film, and Lee intelligently uses the 3D to enhance the space surrounding the action, rather than as a gimmick. Perhaps it’s proof that in the hands of a great director 3D is a step in the right direction, although I still feel as though a film that needs 3D to be great isn’t a great film.

My memory of Martel’s book is limited, but I was suprised when the film adaptation was announced. It’s the sort of project that is far more likely to fail than succeed, and I couldn’t understand why any director would choose to try. That Ang Lee has created a film that is for the most part one of the better studio films of 2012 is almost as miraculous as Pi’s story.