Naomi Watts needs to stop going on holiday in Thailand. The characters she plays, in any case. In 2012 she starred in The Impossible as Maria Bennett, based on a real person named Maria Belon, who was separated from her family by the tsunamis that hit the country in December of 2004 and nearly killed them. Now in Penguin Bloom she stars as Sam Bloom, an actual real person, who became a paraplegic after the rooftop fence she was leaning against snapped under her weight, again on holiday in Thailand. (She’s not a big person; it was an old fence.) Maybe a nice trip to the Whitsundays next time, Naomi?

All kidding aside, Penguin Bloom is the type of movie snooty critics greet as follows: “Oh great, another disease-of-the-week movie where a person recovers their will to live under the loving influence of the family pet.” There’s nothing that makes a critic grumpier than a heart-warming film like this one, as its sheer earnestness breeds cynicism.

What critics are really objecting to, though, is not the message itself, but the likelihood that an uplifting story does not require anything more than the basic skills of filmmaking to be told, and usually does not get anything more than those basic skills. When a film is as imaginatively conceived, as richly acted, and as all-around affecting as Penguin Bloom, it takes the words right out of their mouths, the ink right out of their pens.

The titular bird in Penguin Bloom is not actually a penguin. She’s a magpie who was named Penguin by Sam Bloom’s son, Noah (Griffin Murray-Johnston), who found the bird fallen from her nest – not unlike Sam herself. It’s in the first year after Sam’s accident near the family’s beautiful seaside home in North Sydney (the Blooms’ home is where the film was actually shot). Noah rescues the bird and brings her home to nurse back to health, a gesture that is perhaps inspired by his lingering guilt over his mum’s accident. See, it was Noah who convinced the family to see the view from the rooftop where the accident occurred.

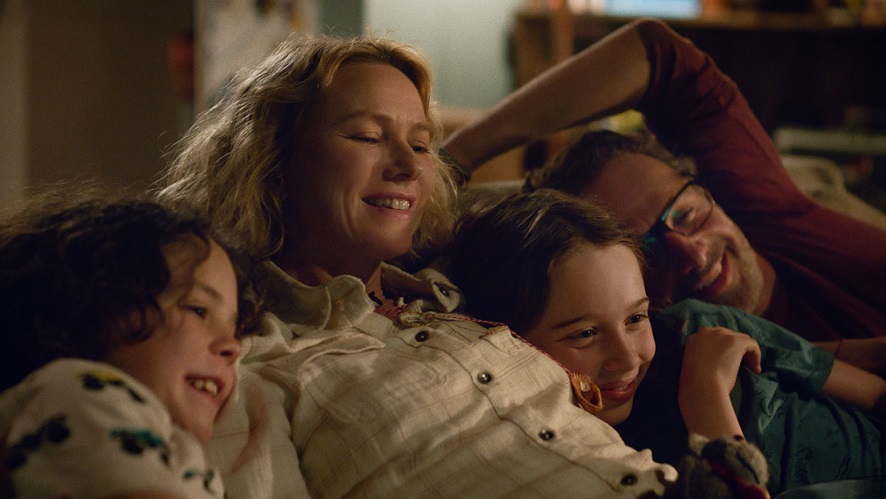

In greater need of nursing is Sam, who is in that predictably miserable period of coming to grips with the fact that your life will never be the same. The change for Sam is even more radical than it would be for most people, as she’d been a surfer and used her legs more than most. Now she can no longer feel anything from her bra strip downward – that’s the reference Sam provides – and no amount of beautiful home and loving family can bring Sam out of her funk. That family also includes her husband Cam (Andrew Lincoln) and her two other boys (Felix Cameron and Abe Clifford-Barr).

Just because you can see where this is going doesn’t make the journey any less emotionally gratifying. The trailers for Penguin Bloom were basically uninterested in creating any suspense about the outcome of the story, tending to give away the whole thing. It doesn’t matter. What matters is the profound humanism director Glendyn Ivin, writers Shaun Grant and Harry Cripps, and the whole cast bring to the material.

Watts, also a producer on the film, is the place to start here. She’s long been a celebrated actress, and her involvement alone should suggest this is not just your everyday disease-of-the-week movie. Throughout her career Watts has been capable of great nuance, and that type of craft is particularly well suited to the vicissitudes of life in a wheelchair. Sam Bloom had been a really good mum, hands on and switched on, and Watts’ portrayal mourns the loss of that active participation in family life as much as it does her obvious physical loss. There’s a moving scene when one of the Bloom kids gets sick on dodgy oysters. Cam returns from being summoned after cleaning up all the vomit, and Sam laments through tears, “They used to call for me.”

The next revelation among the film’s cast is Murray-Johnston, a novice actor with an uncommon sense of how to underplay this material. He does more with his eyes to reveal the depths of his guilt than any words could ever express. Anyone could have called them up to that roof, but it was him, and there are oceans of sorrow in those eyes. That’s not because he plays it up, but rather, because he instinctively knows how to convey his inner life through just a wide-eyed, sidelong look.

The film is narrated by Noah to a point, even though it’s Sam’s story. There’s some inconsistency to the viewpoint here, but it allows for some lovely deviations from our expectations on the filmmakers’ part. As we see Noah ruminate on the events that led to the accident, he calculates the number of tourists who visit Thailand per year, the number of hands that may have touched that fence without any negative repercussions. These passages allow Ivin to go outside the bounds of realism in both the memory of the events, and its fantastical representation in the characters’ minds.

The film might not be the success it is, though, without that bird. Who knew a magpie could convey such empathy? The well-trained bird does a lot of heavy lifting, functioning as comic relief as it hops around the Bloom house, pecking at the kids’ ragdolls, squawking for attention, pooping indiscriminately. But this bird is a true service animal. When Sam throws a fit of impotent rage, shattering a wall’s worth of family photos, the bird flutters around in its own sympathetic distress, appearing to genuinely care for her human companion in so much pain. When she nudges her head into Watts’ cheek, you really believe that a bird could restore a human’s will to live.

Sam’s will is restored by a number of factors, including the loving husband played by Lincoln, the nattering but well-meaning mum played by Jacki Weaver, and Rachel House in peak tough-love form as Sam’s kayaking coach. (House is really having a moment after her work in the recent Soul.) Kayaking, a sport that does not require the use of the legs, may be the thing that really brought Sam back. But there’s no doubt that her family – a family with a bird that has been given its surname – was her best medicine.

If that’s a cheesy sentiment, you’ll have to forgive it, because Penguin Bloom puts you in the frame of mind to forgive any and all earnestness. Audiences may not have a problem with that kind of sentiment to begin with, but when even the critics are sniffling and snuffling near the end, you know it’s pretty special.

Penguin Bloom opens today in Australian cinemas.