Choose life, Mark Renton urged as Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting opened to the roar of Iggy Pop’s ‘Lust For Life’ back in 1996. “I chose not to choose life,” Renton admits, and he’s proud of it. “I chose something else. And the reasons? There are no reasons. Who needs reasons when you’ve got heroin?” In 1996, Trainspotting was dynamic and it was new and it was part of an era of film that helped redefined how films are made and produced.

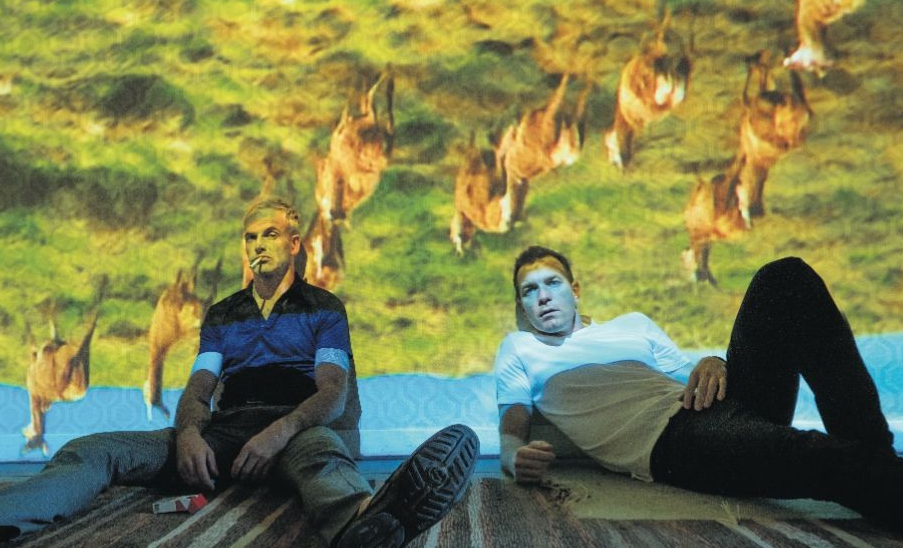

As the end credits rolled, Renton (Ewan McGregor) had chosen life after all. He wanted to pursue stable employment and rid himself of his drug-addled lifestyle But T2 Trainspotting, arriving twenty years later from the same writer, director and cast, suggests that ultimately choice is empty.

The temptation for directors to jump back into the material that helped establish their careers must be great, but the notion is almost always more appealing than the fallout. For every Mad Mad: Fury Road, there are a large handful of films like Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skulls. Danny Boyle recognises that part of his interest in returning to Trainspotting is a yearning for the past. “Nostalgia,” Sick Boy lectures Renton. “That’s why you’re here. You’re a tourist in your own youth.” It’s an acknowledgement from Boyle, whose new film is sometimes more interested in where it’s been than where it’s going, but just because Boyle has a sense of self-awareness doesn’t mean that his sentimentality has creative immunity.

One issure with revisiting a cultural property as iconic as Trainspotting is that expectations must be exceeded, not met, in order for the sequel to match the impact of the first one. It’s not enough to produce a film that is as good as the original. T2 isn’t as good as Trainspotting, but it’s a good film. Whether it needed to be produced is another question, the answer on which depends on whether you’ll allow the existence of one film to affect your affection for another. As grim as the original Trainspotting could be, there was also optimism, and as Renton made away with his stolen money, there was hope. But choice doesn’t matter, according to T2. These characters may be stuck in arrested development for the rest of their lives. Before T2, hope was a possibility, however unlikely. Now it’s an unlikelihood.

It’s not so much a question of quality when it comes to T2 Trainspotting as it is a question of necessity. Trainspotting captured the climate of a time and place so powerfully that you might argue it ought to have remained there. Renton, Begbie, Sick Boy and Spud are no longer frozen in time, back in 1996. Do you want to see these characters twenty years on? Choice has nothing to do with much at all.

Boyle looks to the past for inspiration, rather than pursuing the future. Boyle’s conspicuous nostalgia lets him down. The crowded references to the original Trainspotting begets fondness for it rather than admiration for this sequel. There is a lot of noise, light and vitality to T2 Trainspotting, but underneath the sheen, Boyle has a lot less to say than he did back in 1996.