Bikies in the movies are portrayed one of two ways. They’re either too cool for school, or each one is meaner than the next. That leaves little room for nuance, and nuance isn’t usually necessary anyway, because the bikies are rarely the central characters in these movies.

Jeff Nichols’ The Bikeriders is all nuance. Yes some of the titular characters have tendencies toward one of the reductive binaries listed above. Austin Butler in particular might be cool enough to become the next James Dean, like he never stopped playing Elvis Presley. But most of these bikies are more dorks than they are either menacing baddies or sultry hunks. They talk excitedly about who knows what. They confess insecurities. They try to avoid punch-ups as much as they instigate them. And showing one of them up, even rather brazenly, isn’t always going to draw a predictable response.

This is all to the good of The Bikeriders, which is inspired by a photo book by Danny Lyon – who appears here as a character played by Mike Faist. Between 1965 and 1973, the real Lyon photographed and interviewed members of a biker gang known as the Outlaws Motorcycle Club, fictionalised here as the Vandals Motorcycle Club. Quaintly, it’s a club that developed in the greater Chicago area, and the reason that’s quaint is that many if not most of the characters have thick Chicago accents. It’s hard to be all that threatening when you sound like George Wendt and Mike Myers in that Saturday Night Live sketch about NFL coach Mike Ditka.

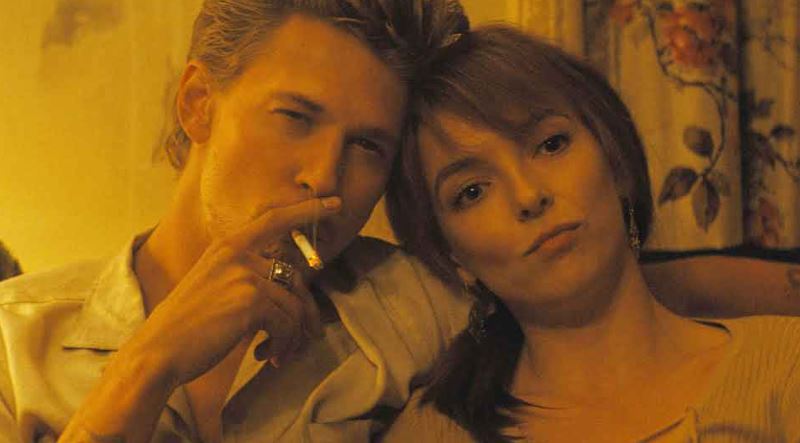

The evocation of a sketch comedy show is appropriate, because The Bikeriders is regularly funny. Starting things off on the right note in that regard is Jodie Comer as Kathy, an outsider to this life with the very thickest and most delightful of the Chicago accents. She remains fundamentally a square dressed in plain clothing even after she stumbles her way into marrying Butler’s Benny. Although we hear other characters’ voices in an interview style, the majority of what we see here is formed from interviews with Kathy, usually taking place in her kitchen as she makes coffee, gesticulates a lot, and goes off on loopy tangents.

The other characters she brings into focus are her husband, the smouldering and mostly silent Benny (Butler); the chapter head, Johnny (Tom Hardy), who got the idea to form the club from a Marlon Brando movie; Brucie (Damon Herriman), his deputy; Cal (Boyd Holbrook), a refugee from a California biker club, and Funny Sonny (Norman Reedus), the member from that club sent to mess Cal up, who instead joins the club; Zipco (Michael Shannon), a Latvian with a screw loose; and Cockroach (Emory Cohen), who eats, you guessed it, cockroaches. The film is a tapestry of their experiences as this lifestyle goes from innocuous and alluring to dangerous and divisive over a period of years.

Nichols is pulling off an interesting trick with the perspective here, putting our outsider status through a double filter. We’re seeing this world through the eyes of a person interviewing a person who herself is an outsider. At the same time, Lyon’s embedding with the club for a number of years gives us an unusual intimacy with these characters, such that we get a sense of the forces that shape them and the lessons they learn even though we never really see them outside the context of their involvement in the group. The exposure to this group is generous, as we really live with them. That’s a lot to extract from a book of interviews and photographs, and Nichols’ screenplay does it expertly.

Comer works exceptionally well as our surrogate. We understand how she is both perplexed and entranced by these bikeriders, in a simple expression on her face while Benny is pursuing her the first night she meets him. This expression seems to simultaneously question what she’s doing here, and also consider it the most natural thing in the world, an arrival in a place she never knew she was supposed to be.

And yet she does remain an outsider. The poster for The Bikeriders is a little misleading, as it shows Comer in the same black Vandals jacket that the others wear throughout – a jacket that leads Benny to get stomped into pulp for his refusal to remove it. Yet Kathy never goes “full Vandal.” She only exists within the orbit of this group because of her relationship to Benny, and when she talks about it with Lyon, she’s as much the disinterested observer as he is.

Although The Bikeriders figures to continue burnishing Austin Butler’s growing reputation as a matinee idol, the most interesting character here is Johnny, the bikie played by Tom Hardy. As mentioned previously, the character created the group after watching Brando’s The Wild One, but Hardy is a bit of a Brando acolyte himself. Over the years he’s found himself cast in roles that leveraged his incendiary nature to produce the sense of a simmering threat that could explode at any moment. Johnny does not regularly explode, or at least not as often as you would think, and his responses to people who challenge his authority is a strange patchwork of choices that reflect the real stakes a real human being faces. It’s electric work that is underplayed in the best possible way.

Nichols’ latest entry in a growing oeuvre that features marginalised Americans in rural environments is possibly his best to date. That’s saying quite a bit for a man with Shotgun Stories, Take Shelter and Mud already on his resume. The Bikeriders has a clarity of purpose that is not undercut by its lack of a traditional narrative structure. It’s high concept and low concept at the same time. Excellent films contain multitudes. And so, apparently, do bikies.

The Bikeriders is currently playing in cinemas.