Over the course of Fred Rogers’ long career, smitten admirers characterised his distinct gifts in many different ways, but “therapist” may have been the most apt. Whether talking to children or talking to adults, Fred “Mr.” Rogers rarely provided the response his conversant expected, or thought they wanted. More often it was some mildly evasive inversion of how to ask the question – if he said anything at all. Very therapist like, you will agree.

That approach might have been maddening for adults – pleasantly maddening, usually – but it went over like gangbusters with kids, and in either case, had the effect of getting the conversation around to where it really needed to go. Even as consummately verbal as a television host must be, Mr. Rogers was never one to fill the air with comfortable bullshit. He’d rather say nothing at all.

Marielle Heller’s movie about Mr. Rogers, A Beautiful Day in the Neighbourhood, approaches its subject in a similar way to how its subject approached his “subjects.” (Not an entirely inaccurate description, as Rogers was the hand controlling the puppet monarch King Friday XIII.) As a film, it does not always provide the immediate answers we think we want, but rather, the answers we understand we need, upon further reflection.

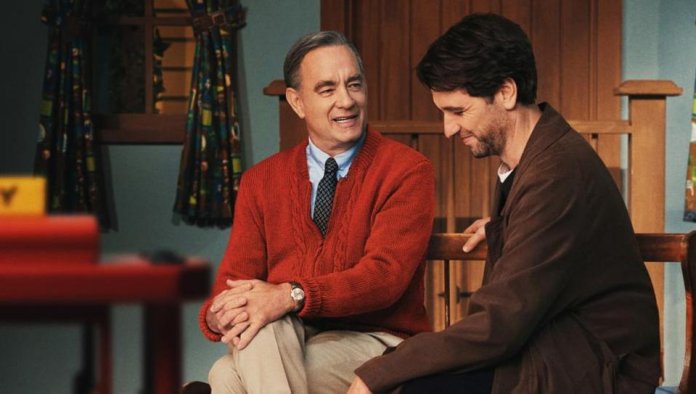

At one point, magazine journalist Lloyd Vogel (Matthew Rhys) asks Rogers (Tom Hanks) what the difference is between Fred Rogers, the man, and Mr. Rogers, the character we see him playing on TV. The response we expect, of course, is that there is no difference. But Rogers doesn’t give it. A knowing look passes across his face before he pivots the conversation and asks Lloyd his own question. A lesser film would have told us that there’s no difference between the two, but this greater film is going to show us.

It’s not actually Fred Rogers’ story, but the aforementioned Lloyd Vogel’s, and it’s inspired by a true one. It’s 1998, and Lloyd has been hired by Esquire magazine as an investigative journalist, an assignation that has already won him a magazine journalism award. But his pull-no-punches approach to reporting has burned some of the good will of his potential interview subjects. His editor (Christine Lahti, welcome back) has assigned him what amounts to a 400-word puff piece on Mr. Rogers for their “heroes” issue, in part to get around the embargo against Lloyd, but in part to challenge him to go outside his comfort zone. Lloyd’s eyes roll so hard, he might need to see an ophthalmologist.

But he does go to Pittsburgh to have what he thinks will be one short interview with the beloved children’s show host, and that will be that. He sits in on the filming of some of Rogers’ show, and is bemused and perplexed by the man. This continues when Rogers gently turns the tables on him during their 20-minute interview, asking the journalist about his father instead of answering Lloyd’s questions, like a good interview subject should. See, Lloyd’s got a scar on his face, one that came from a fight with his estranged dad at his sister’s wedding. Lloyd didn’t get the scar from his dad, but from another wedding guest, who punched him after Lloyd punched his dad. Mr. Rogers correctly identifies a “broken person” who needs him, even if he may not think he wants him.

A Beautiful Day in the Neighbourhood presents a familiar arc of a jaded, angry person recovering his sense of equilibrium through forgiveness and accepting the love of others. It’s all about the how’s in terms of this film’s effect on its viewers. It’s moving to see the gentle but determined prodding of Hanks’ Rogers as he pushes Lloyd to the places he needs to go, starting with conjuring a memory of Lloyd’s beloved stuffed rabbit from when he was young, given to him by his mother, who died back then. We feel ourselves undergoing the same sort of benevolent hypnotism back to our own cherished childhood items.

Heller understands the effect Mr. Rogers had on all of us, an effect Hanks is able to perfectly recreate. She uses the tools of cinema to put us completely in Lloyd’s shoes, a type of subjectivity that Rhys’ humanistic performance makes all the easier. But it’s really the shoes of any viewer, any person Mr. Rogers was talking to as he looked out of the screen directly at us, that Heller puts us in. Or really, it’s putting us back in our own shoes, the shoes we wore when we were much much younger, which would no longer fit us in any way except metaphorically. Mr. Rogers literally looks out the screen at us in this movie, as scenes – imagined or otherwise – from his show are lovingly recreated here. But Heller also allows this Fred Rogers to look out at the movie audience in at least one stirring scene, breaking the fourth wall in a way that cannot be confused for just the artifice contained within the movie’s narrative.

Any doubts that an icon like Tom Hanks would be able to slip into the skin of an icon like Fred Rogers were unwarranted. We believe Hanks as Rogers from the film’s opening moments, in which he does an excellent recreation of Rogers’ opening routine: Singing his show’s theme song to us while hanging his jacket in the closet, then putting on his zip-up jumper and sneakers. There’s a profound sense of time travel back to whatever age we last were when we watched Mr. Rogers’ show. And since the show aired from 1968 to 2001 with only a short three-year break somewhere in the middle, many viewers of Heller’s film did indeed have that experience. Hanks has been nominated for an Oscar for getting it so right.

The details of Lloyd’s story have a sort of necessary universality, even if the specifics may not apply to any one particular viewer. Lloyd’s father (Chris Cooper) walked out on his family when his mother was dying, having slept around on her. He’s been absent from the lives of Lloyd and his adult sister (Tammy Blanchard), but is now trying to make amends as he sees his own mortality around the corner. It’s a truly pregnant subject for Lloyd as he has just become a father himself, and is determined not to make any of the same mistakes with his newborn son and his own wife (Susan Kelechi Watson). But he’s got a job that he loves and that often takes him on long trips, so he knows the potential is there to drift away, just as his dad did.

These may not mirror your exact circumstances as a viewer, but they remind you of someone in your life who may have hurt you the same way Lloyd’s dad hurt Lloyd. Modern-day saint that he is – although his wife does not like the term – Fred Rogers focuses not on the negativity of the people who caused this hurt, but on the positivity of the “people who loved you into being.” Viewers will feel the urge to pack away their cynicism, just as Lloyd does.

Heller is uniquely suited to some of the more magical realism-inspired elements of the story, as she used fantasy cutaways extensively in her remarkable debut, Diary of a Teenage Girl. She takes us on a number of trips in this film; there’s the obvious emotional trip inside our own open wounds, but we take trips deep into the set of the TV show as well, as Heller shrinks Lloyd down to the size of Daniel Tiger and King Friday in the Neighbourhood of Make Believe. The whole package is one of great empathy and warmth, and it contains nary a misstep.

Heller had an unenviable task releasing this film only a year after Won’t You Be My Neighbour?, Morgan Neville’s excellent documentary on Fred Rogers that came out in 2018. While that film contained a more literal form of “time travel” by providing us access to our memories of the actual show, Heller’s film does something more powerful and uniquely cinematic, deepening Neville’s themes through tools that only a narrative film would allow. If Fred Rogers was indeed a modern-day saint, he deserves a film that unabashedly travels somewhere otherworldly.