There’s a desolate quality to the remote regions of Australia and New Zealand that make them the perfect environments for malicious people to prey on innocent ones. It’s the type of thing explored in an Australian movie like Wolf Creek, and a similar tone hovers over the new Kiwi film Coming Home in the Dark, which debuted last month at MIFF and is now available in Australian cinemas – those that are not in lockdown, anyway. Where Coming Home differs from Wolf Creek, though, is the meaning behind the meaningless violence that befalls its victims. As in, there may be some, though it may be stumbled upon by happenstance.

Hoaggie (Erik Thomson) is an affluent teacher who’s on holiday in the country with his wife Jill (Miriama McDowell) and their two teenage boys (Billy Paratene and Frankie Paratene). They’ve pulled over for a little picnic along the water when two men walk up to them, oozing bad intentions. Instinctively they know to be wary of the scruffy looking Mandrake (Daniel Gillies) and Tubs (Mathias Luafutu); there’s something insidious about them, and besides, strange men don’t just wander up to vulnerable families if they don’t mean harm. One strange man might be mentally ill, but two mean trouble.

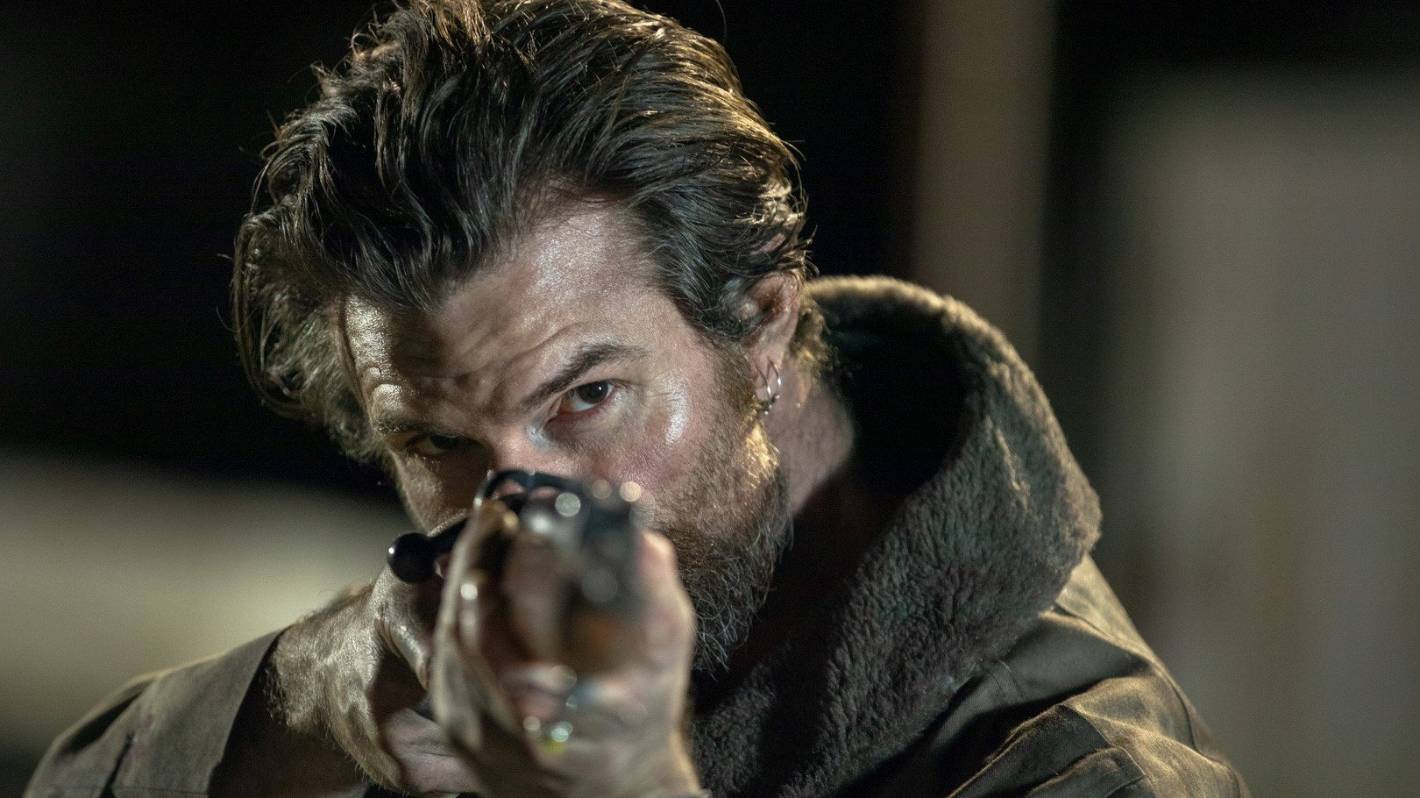

When Mandrake pulls out a shotgun not long into the interaction, Hoaggie’s and Jill’s suspicions are confirmed. At first it only seems as though the men want to make off with their car and whatever money is in their wallets, but a random occurrence tips them off to who they’ve got here under their thumb. One of Hoaggie’s sons uses his nickname, and Mandrake recognises it as the nickname of one of the teachers who worked at a boys home where Mandrake was abused as a child. Now this is just not a crime of opportunity, it’s an opportunity to teach Hoaggie a lesson.

To say things spiral from here is an understatement. Coming Home in the Dark is the type of movie you should warn potential viewers about when reviewing it, though not necessarily because it contains material too graphic for squeamish audiences to watch. There’s physical violence in James Ashcroft’s film to be sure, but the thing that makes it so challenging is its bleakness. Anyone who found themselves in that situation might hope they could rely on a core nugget of humanity that would prevent certain lines from being crossed. Mandrake and Tubs are not acquainted with such bourgeois safety nets.

As shocking as it can be, Coming Home in the Dark might have been better off if it just lived in that Wolf Creek zone of meaninglessness, where the evil that men do sometimes cannot be explained, except by something in their core that revels in chaos and cruelty. By introducing the notion that these two drifters were abused when they were boys, it creates a certain topicality to the themes that undermines their wilder and more frightening edges.

Mandrake and Tubs are established as symbols of a sort of nihilistic misanthropy with which you cannot negotiate. Ashcroft makes a memorable artistic choice in his early depiction of Mandrake, as he backlights actor Daniel Gillies by the late afternoon sun as he stands there, statuesque, holding his shotgun. The effect is to render Gillies’ face completely black, though emanating a blinding white light from behind. In just one image, we understand that this thing that has pinned this family to the ground is sort of otherworldly and impossible to know or understand.

Spending so much time with Mandrake as we do over the course of the narrative, though, we are forced to reckon with him as a real person. His actions would make it far easier for us to just dismiss him as a Villain with a capital V, and he’s more frightening that way. However, it may not be Ashcroft’s intention just to deliver another stylish contemplation of violence and evil, or if so, not just one from the perspective of the victims. There are victims on both sides in this film, and it seems equally possible, depending on how culpable you find him, that Hoaggie is the Villain with the capital V. Whether that’s a useful thematic agenda in this film is debatable. There’s a certain purity to presenting the horribleness that goes on here without supplying pat explanations for it.

Ashcroft’s promise as a filmmaker shines through like that sun against the back of Mandrake’s head. The longtime actor, who appeared in the gonzo horror comedy Black Sheep, has plied his skills behind the camera in a series of short films, but this is his first feature-length directorial effort. You can sense something of the converted shorts director in him, though. The very small amount of plot in Coming Home in the Dark suggests a talented imagemaker looking for something more substantial that confers greater credibility within the industry.

In the effort to keep it a surprise, little of what happens has been revealed in this review. But the script fails to pay off most of the potential narrative pivot points it introduces. Efforts by the family to extricate themselves from the situation need not always bear fruit, but they can’t all just be narrative dead ends without damaging the overall momentum and giving the story a meandering quality that never resolves into something satisfying. When a man accustomed to making ten-minute films has to make a 90-minute one, there’s inevitably some wheel spinning. This is probably exacerbated by an early choice that is designed to shock us, but leaves the movie trying to recover from losing the narrative possibilities that are closed off by that choice.

There’s no doubt that Coming Home in the Dark is a film that will get under viewers’ skin in a way that will leave audiences talking about it, and some of them shell-shocked. The vitality in the filmmaking elevates it artistically, as well. In losing its way over the course of the narrative, though, it sacrifices its opportunity to be something special, rather than just something bleak.