It takes a certain leap to accept a medium that I love rendered through the lens of a format that I try to avoid when possible. I am a member of Facebook. I had an Instagram for a few days. I have never had Twitter (although ReelGood has, seldom used), I don’t really know what Tumblr does and the brief life of my Snapchat, a number of years ago, was primarily dedicated to drawing penises on things, a joke that nobody found particularly funny.

And yet I am constantly engaging with computers, we all are. Whether or not that truth alone justifies the recent upsurge of films that are set entirely within the framework of a computer, I’m not sure. But I have now seen two such films that have justified this movement themselves. The first was Unfriended, a film that astutely exploited the functions of Skype to convey information. That film wasn’t a gimmick, or at least it engaged with its gimmick so cleverly that it overruled its gimmick.

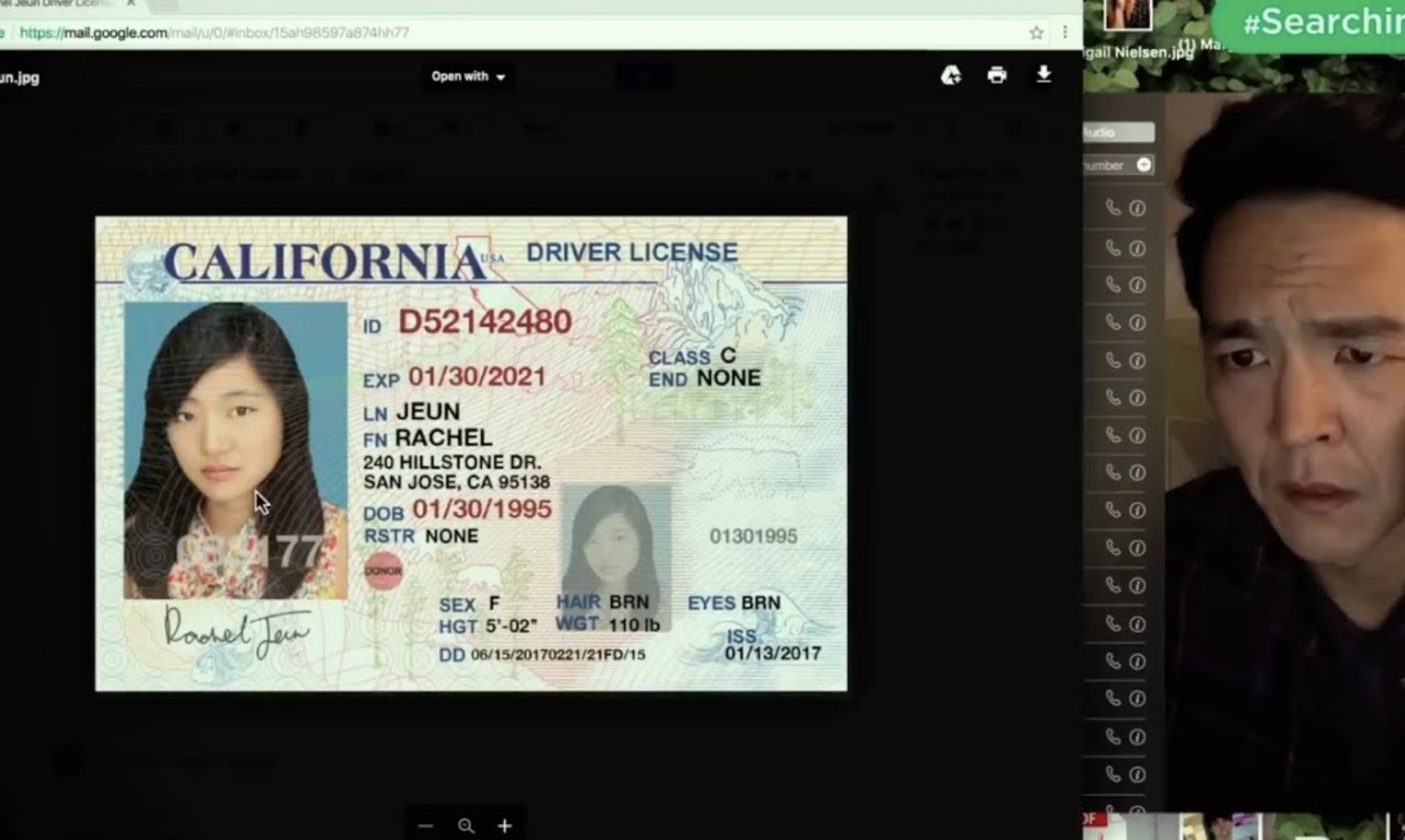

One method in which it did this was as in the way we would see one member of the four way Skype chat type something in their screen, then delete it and type something else. This concept is also utilised well in Aneesh Chaganty’s new film Searching. It’s a way of conveying a characters’ feelings without laboured exposition or character development. Stop for a moment to consider how difficult this might be in a film set in a computer. Some of the most poignant moments in Searching are constructed around the image of a mouse button, hovering over an icon. Whether the icon is clicked or not clicked can tell us plenty.

Sometimes Searching uses video – YouTube, digitally broadcast news bulletins – to include footage, but it is always neatly within the central approach. Rarely does Chaganty’s need, within his own constrictions, to adhere to those constrictions feel so laboured that it shatters the illusion of the narrative he has cleverly constructed.

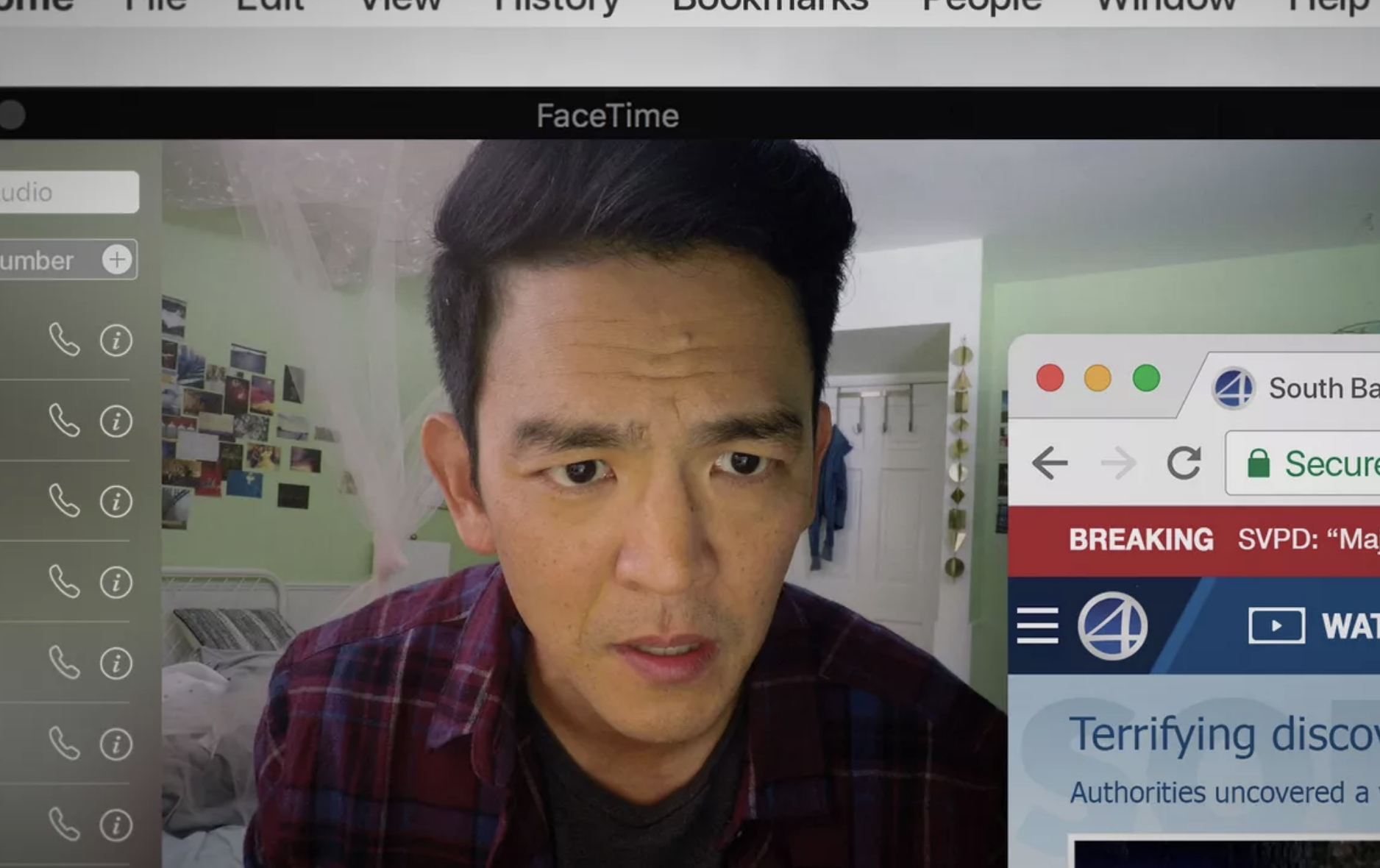

Cho’s presence is paramount to the success of the film. Acting for a computer must be no easy feat, channelling a character that would or could conceivably hunt for his missing daughter almost entirely online believably is something else but Cho also manages to infuse his performance, and consequently the film, with an unexpected degree of emotion. It is is finest performance to date.

Chaganty is no stranger to digital pathways for storytelling. His short film, Seed, a film made for Google Glass, became an internet sensation, prompting the mega company to recruit Chaganty to continue pursuing his train of thought. There are moments in which Searching is forced to employ formats that feel less neat than others, recalling the approached of the often less clever found footage films, but for the most part, Chaganty understands and uses his format shrewdly.

Perhaps most astonishing about Searching is that it is not simply a good, tense thriller for a film set on a computer, it is just a good, tense thriller, perhaps the best of the year. I certainly don’t believe that all filmmaking ought to migrate to an operating system but it is a welcome surprise, and perhaps a bit counterintuitive to how I generally feel about cinema, that the two I have seen have been as good as they have.

There is a moment in the first act of Searching in which the entire screen is occupied by a screensaver that I recognised well, and I’m sure many of you will too. I’ve seen that screensaver countless times, on countless screens, and never once took in the sense of mystery, beauty and dread that Chaganty evokes in it. In his hands, the screensaver becomes one of the most memorable images of cinema this year. If that is not an example of making the most of a cramped format, I’m not sure what is.