People who think they’re in a happy relationship are understandably taken aback by being dumped. The evidence that it was going to happen may have been there, but they were too wrapped up in ignorant bliss to see it. One day, the usual laughs and smiles of the discontented party may have been slightly forced, yet still present. The very next, they were jack of it, and the sudden total withdrawal of their affections seems harsh to the dumped indeed. It’s painful enough when this is a romantic relationship, but when it’s a friendship, unbound by the strictures of exclusivity, it’s all the more acute.

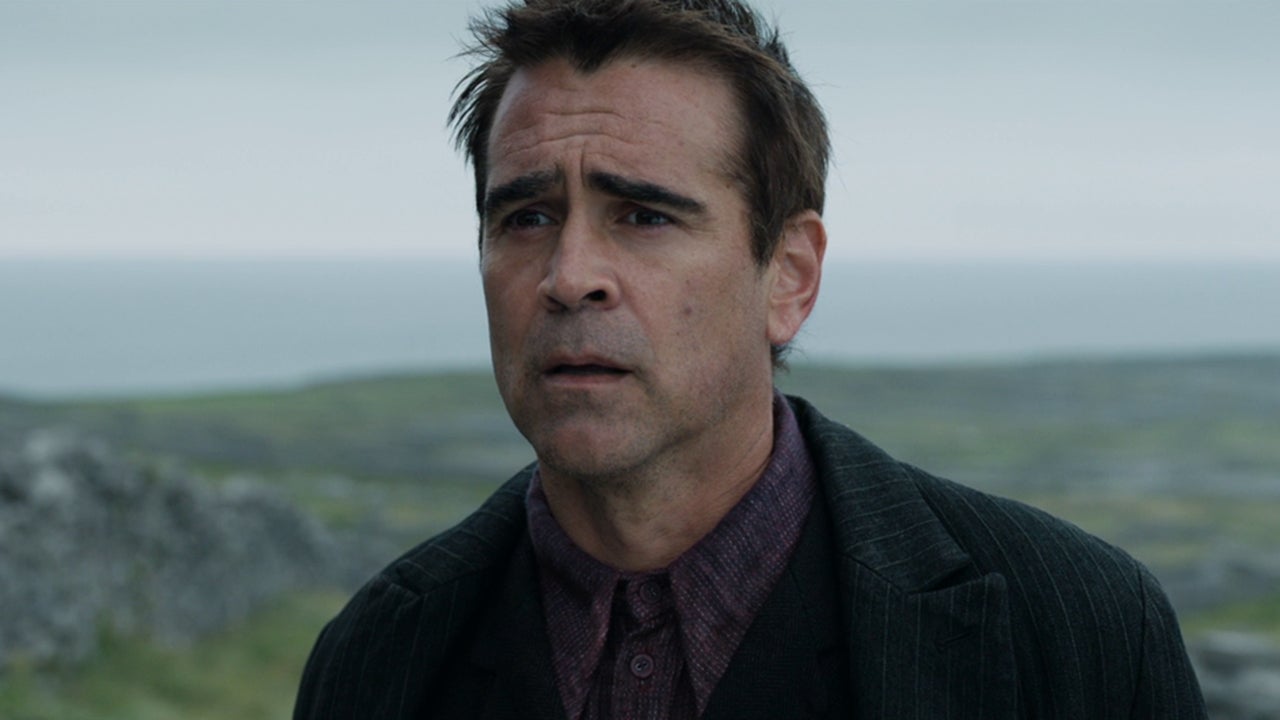

There’s no suggestion that the relationship between Colm (Brendan Gleeson) and Padraic (Colin Farrell) in Martin McDonagh’s The Banshees of Inisherin is anything other than a heterosexual male friendship, though the brilliant thing about art is that we can read into it whatever themes speak to us personally. There are obvious ways that what happens between these men is a metaphor for something else entirely, as the 1923 film is set against a backdrop of the Irish Civil War. McDonagh doesn’t disguise his notion that the overnight dissolution of a friendship between two drinking buddies mirrors the state of war between countrymen who have more in common than they don’t. He needn’t, when the apocalyptic air is as palpable as it is here.

It is indeed a rude awakening for Padraic when he tries to sidle up next to Colm at the pub and is told to sit somewhere else. Colm’s news: He no longer likes his former friend. “You do like me,” Padraic counters. “You liked me yesterday.” On the small island of Inisherin, it’s a problem when you don’t like one of the other 53 people on the island – and if that’s an exaggeration of the smallness of the setting, it isn’t by much. Even if the pickings for other friends weren’t so slim, Padraic rightly feels he deserves an explanation for what changed between them to cause this break. He doesn’t believe he said anything unforgivable when he was drunk, though that sort of thing has happened before.

Unlike the ends of other relationships, which bystanders see coming, the other islanders are equally befuddled by Colm’s capriciousness. Colm ultimately does start offering half explanations, like that Padraic is dull. “But he’s always been dull!” responds Padraic’s sister, Siobhan (the excellent Kerry Condon). It turns out Colm thinks that every wasted conversation with Padraic prevents the accomplished fiddler from completing his contributions to the realm of music, the thing about him he hopes will outlive him. By contrast, the thing that Padraic thinks he offers – that’s he’s nice – has no hope of immortality.

Yet Colm is still content to expose himself to other dullards on the island, like the corrupt and violent local police officer (Gary Lydon), who abuses his own half-witted son (Barry Keoghan). As Padraic simmers on the other side of the pub, trying to figure out how to mend whatever’s gone wrong between them, Colm ups the stakes on their feud to demonstrate how seriously he is. He tells Padraic that every time Padraic attempts to speak to him, he will physically disfigure himself.

There’s a lot of rich thematic material bound up in McDonagh’s best film since In Bruges, which also starred Gleeson and Farrell. Although Padraic is the wronged party here, he’s not blameless. Because it’s not possible to avoid the similarities to a romantic partnership, McDonagh examines the way people take their partners for granted – stammering, after the fact, that being nice should have been enough. Without having worked to actively maintain the relationship, it died, and the sorrow of that loss turns into intense frustration, even rage, at the person who ended it.

Of course, McDonagh would also find it banal if a viewer’s big takeaway from The Banshees of Inisherin were that people need to be more engaged partners to allow their relationships to flourish. The material is richer when we return to finding Padraic guiltless. Colm regularly gives confession to the island priest, and here we see a doubt emerging that God cares about his creatures in the way a benevolent creator should. As is especially resonant in the time of COVID, we see one undeserved hardship after another befall Padraic over the course of the narrative, clenching our fists at how the world treats people who just try to exude positivity. That, however, would also be too banal of a reading of what McDonagh is saying here. You can only ever scratch the surface of what’s on his mind.

The preoccupation with death is strong in this one. For an artist like McDonagh, contributing to the world in a way that will outlast your flesh feels like an earnestly felt endeavour. DP Ben Davis shoots this beautiful landscape with misty, sepulchral overtones. The sardonic wit of the Irish has a perfect platform in Banshees of Inisherin, but as funny as it is at times, there’s a gloom that suffuses the proceedings. Never mind that there is an actual character who functions as an angel of death. That’s Mrs. McCormack (Sheila Flitton), whom the islanders give as wide a berth as possible, and who can forecast future calamity with proven accuracy.

McDonagh doesn’t do anything so ordinary as present us with what appears to be an idyllic community, then steadily reveal the rot at its core. Rather, the idea is that it’s all rotten, all hanging precariously between life and death. We never see the mainland where the opposing sides of the civil war are firing at each other, only the tufts of smoke from their gunshots on the horizon. In McDonagh’s view, the whole world is eating itself from within, and this is just one small pocket of it.

These heady ideas mightn’t translate to us without the faces the actors put to them. Farrell’s face in particular is impossible to resist when doling out our sympathies. He’s too honest of an actor to resort to cheap sentiment, but the pained way he screws up his expressions, with every new arbitrary way Colm devises to dismiss him, gets us anyway. We believe that a pure-hearted soul like him might be too good for this world. Colm should be comparatively sinister, but Gleeson convinces us of his conviction in what he’s chosen to do, for reasons he considers valid. It’s also clear this choice doesn’t come free and easy to him, but he believes he needs to adopt this non-negotiable stance to get what he wants. After all, if you offer any encouragement to an ex, you’ll never get rid of them.

And yet he does offer moments of possible encouragement, where he continues to demonstrate compassion for his former friend, making it all the more confusing for Padraic, and pointing things toward all the more messy a resolution. Such is the state of civil war.

The Banshees of Inisherin is currently playing in cinemas.