Just imagine you woke up one day and … no no, that isn’t right. What if you thought you were alone in this world and suddenly … no no, that isn’t it either. Any attempt to lay out the premise of the documentary Three Identical Strangers feels hackneyed, not because the premise is hackneyed, but because it is so outlandlishly high concept that it can only be introduced in the language of Rod Serling, or maybe a circus barker. Yet this is not a screenwriter coming up with something too crazy to be true; it really happened.

In 1980 in upstate New York, a 19-year-old man named Robert Shafran went off to university for the first time, only he was being welcomed to a campus he’d never visited as though people already knew and loved him. That’s because they thought he was Eddy Galland, a student who had attended the previous year and had decided not to return. Eddy’s closest friend, who knew he was not coming back, found Robert and stuffed him in a car, driving him down to Long Island to meet Eddy, who was more than his spitting image. Turns out the two had been separated at birth, to use a phrase rarely seen outside of tabloid newspapers and soap operas.

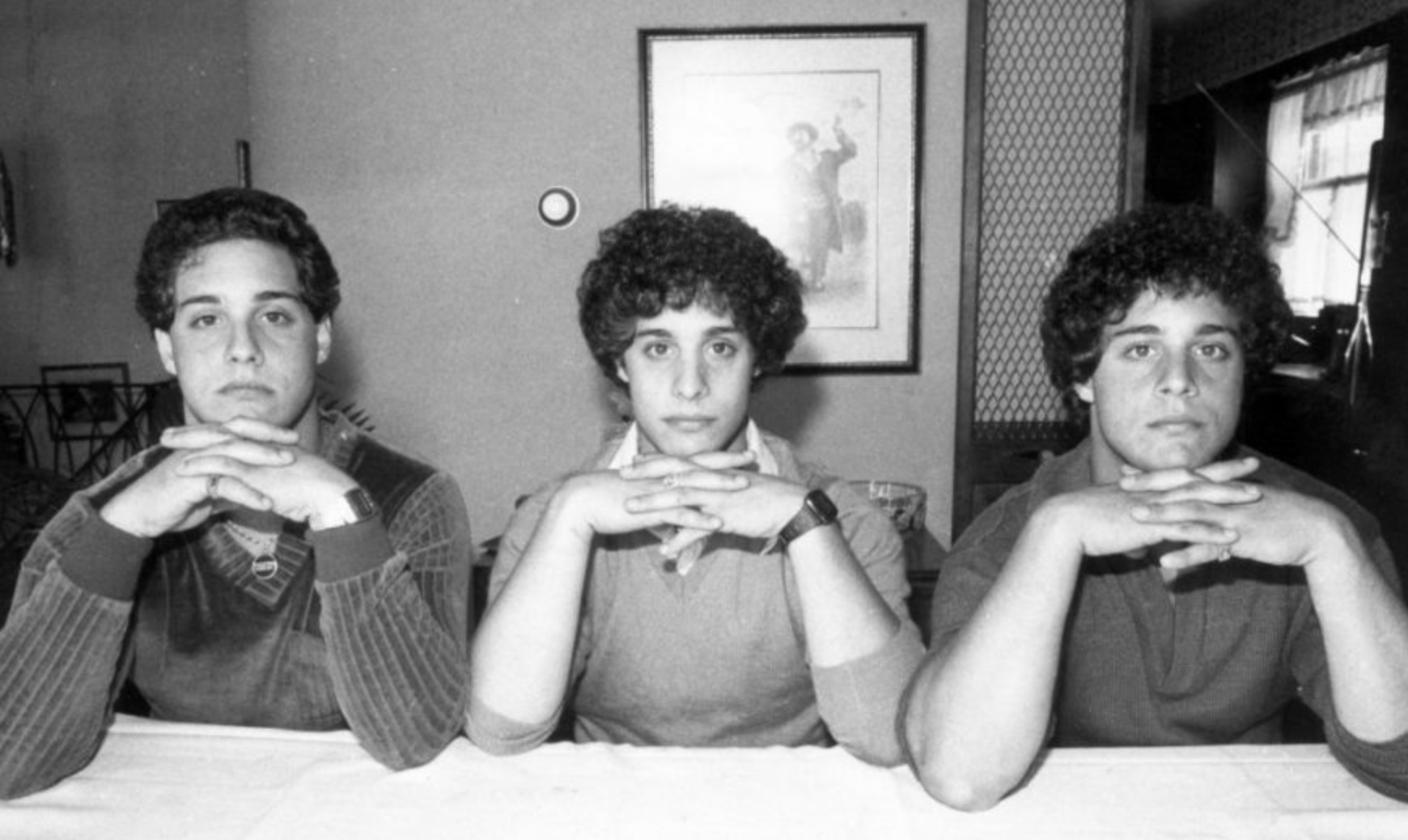

They weren’t alone, either. When their story made local headlines, it drew the attention of another 19-year-old man, David Kellman, who was suddenly looking at a picture of two guys who looked just like him … and were also born on July 12, 1961. After 19 years apart, three babies who’d been adopted to three different families were suddenly hugging each other and posing for photos like they’d lived their lives together. That they didn’t, and why they didn’t, is the subject of the rest of the film.

Only this much of the story should be revealed, because it goes to unexpected places … more unexpected places, that is. But an obviously inevitable byproduct of such a scenario is that what makes the men uncannily similar, but also what makes them different, is something they had the unique opportunity to explore, and issues of nature vs. nurture take centre stage.

Three Identical Strangers is the ideal subject for a documentary, especially at a time when the threshold for what makes an interesting doco is getting lower and lower. The majority of documentaries we get these days seem to be about a person, living or dead, who contributed something unique to the social, cultural or political landscape. And though there’s a lot you can do within those guidelines, and though many of these films receive a lot of acclaim, they develop a certain sameness that ultimately undercuts their lasting impact.

Three Identical Strangers has no such problem, as story is first and foremost. You couldn’t have cooked up a better one than this. That the third brother found the other two is probably the less surprising of the coincidences that underpin this story, given the way their story was covered in the media. But the idea that the first two would meet, solely because they happened to attend the same university a year apart, is the kind of stuff you wouldn’t believe if delivered to you in a fiction film. In fact, eye rolling might ensue.

Upon learning about each other, they discover that all three had competed in high school wrestling, and that all three smoke the same brand of cigarettes. Is it possible you could be genetically preprogrammed for a particular preference in blends of tobacco?

Tim Wardle constructs his narrative as a series of talking head interviews, photos and footage from the time, and even the occasional recreation of key elements of the story, though never in a manner that becomes hokey. It’s his keen sense of how to tell the story that really distinguishes itself, as information is meted out strategically to increase the dramatic impact of certain revelations. That’s not a revelatory approach to telling a documentary story, but it’s executed expertly.

When the revelations come, suffice it to say they are not all happy ones. A story that starts with the young men celebrating their interrelationship via drinking and carousing through New York of the early 1980s, where they were treated like celebrities, does not end there. And it causes us to really ponder the profound damage that can be done when an adoption agency chooses to separate those whose bonds exceed merely that of siblings. Their reunion was heartwarming, but the better outcome might have been never needing it, and instead just growing up as ordinary triplets, in anonymity.