The Lazarus Effect.

Making a decent film is a challenge, but some films have it harder than others. These films managed to claw their way to relevance despite coming from genres that were stagnated, obsolete, or just plain dead.

Blaxploitation: Jackie Brown (1997) | dir. Quentin Tarantino

Blaxploitation all but died out as a mainstream genre in the late ‘70s, the same decade it was conceived. Like all subsets of the exploitation film, Blaxploitation had mined its resources quickly and aggressively. It’s important to note that Blaxploitation films were not exploitative of black Americans, but rather of the American audience’s appetite for films about black culture, particularly those containing action, guns, and masculine heroes (even the female ones).

Twenty years after the decline of Blaxploitation, Quentin Tarantino Jackie Brown echoed the genre in many ways, yet stood apart from it. Its title is a reference to the Blaxploitation classic Foxy Brown (1974), and Pam Grier stars as the heroine in both films. Unlike his later effort at dealing with Blaxploitation in Django Unchained (2012), Tarantino’s Jackie Brown is a surprisingly sophisticated effort to explore the issues of race and gender representation in the Blaxploitation genre.

Samuel L. Jackon’s Ordell is the epitome of what the Blaxploitation hero used to represent: violence, street smarts, and a masculine image of independence. But the film is not about Ordell. The titular Jackie Brown isn’t a vessel for gratuitous violence repackaged as female independence as in Foxy Brown, nor is she a femme-fatale whose independence relies on a steady diet of hardboiled men. Jackie Brown is smart, cool, and responsible. She’s not an action hero by any stretch, and yet she is the most independent and activated character in the movie.

The film is a stark departure from the Tarantino stock: he employs violence infrequently and depicts it conservatively; the soundtrack simply reflects the classic Blaxploitation films of the ‘70s rather than comprising of hand-picked tracks. In fact, it’s the only Tarantino film that cannot be placed in the “Quentin Tarantino” genre; the film is a stripped-down, concerted effort to portray a strong, individual black female hero without resorting to spectacle or forcing the white male perspective.

Genre Parody: Tucker & Dale vs. Evil (2010) | dir. Eli Craig

The genre parody arguably peaked in 1970-80 with films like Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles (1974) and Spaceballs (1987) achieving relative critical success and a cult following. The Scary Movie and Austin Powers franchises notably found some critical and commercial success in the late ‘90s and early 2000s; however, the many sequels and other spin-off titles spawned by these in the coming decade would increasingly fail to appease critics and attract audiences.

In 2010, Tucker & Dale was a surprising critical hit. Though clearly enhanced by great comedic performances, much of its success should be attributed to the fact that it works as a standalone movie – while mainly a response to horror genre and its subsets, the film has a solid narrative, rich characters, and a great sense of humour that all draw from the film’s premise. Additionally, the film manages to evoke the tropes of past horror films without having to rehash their famous scenes.

Tucker & Dale avoids the temptation of emulating Mel Brooks’ cheekily obnoxious fourth-wall breaking humour, as well as the common left-turn into prolonged throwaway gags that has maligned many of the past decade’s attempts at genre parody. The film maintains an almost clinical ridicule of the genre’s tropes, but also quite readily commits to them in a way that demonstrates an obvious affection for the horror genre.

On top of providing an amusing commentary on the horror genre and its effect on the young American audience, Tucker & Dale is itself a rather sweet and funny film – and more importantly, it’s a film that doesn’t have to sacrifice its own qualities to riff on its chosen genre.

Western: McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) | dir. Robert Altman

Though Westerns are still produced and have been rather consistently since the ‘70s, they’ve largely struggled to capture worldwide audiences as they did throughout 1930-65. With the genre’s tendency to reflect modern America, the Western has needed to constantly shift to stay relevant; as David Cook notes in Lost Illusions, people began to question the political violence of America after the Vietnam War, and the violently patriotic values of the Western started to seem out of place in any realistic reflection of the nation.

McCabe & Mrs Miller explore the senselessness of violence in the West, representing it as a force of destruction rather than an inexplicably redemptive act of social rejuvenation as in the traditional and spaghetti Westerns. Though the titular McCabe projects himself as a classic Western hero, his economic interests make him irreconcilable with the John Wayne and Clint Eastwood archetypes of the traditional and spaghetti Westerns – McCabe as a businessman is tied down to his town, his business, and his people.

Altman’s vision of the West is a unique, snowy aesthetic that largely avoids the Western’s typical sprawling shots of nature, favouring instead the warm intimacy of small-town log interiors. The scenes are slow and thoughtful, and the vision of America that they portray is bleak.

Though the aforementioned Blazing Saddles would eventually drive the Western and its tropes further into oblivion, McCabe & Mrs. Miller would inspire a new modernist approach to the Western that favoured the economic struggles of the frontier over the traditional good vs. evil construct of its predecessors to better reflect the anxieties of its audience.

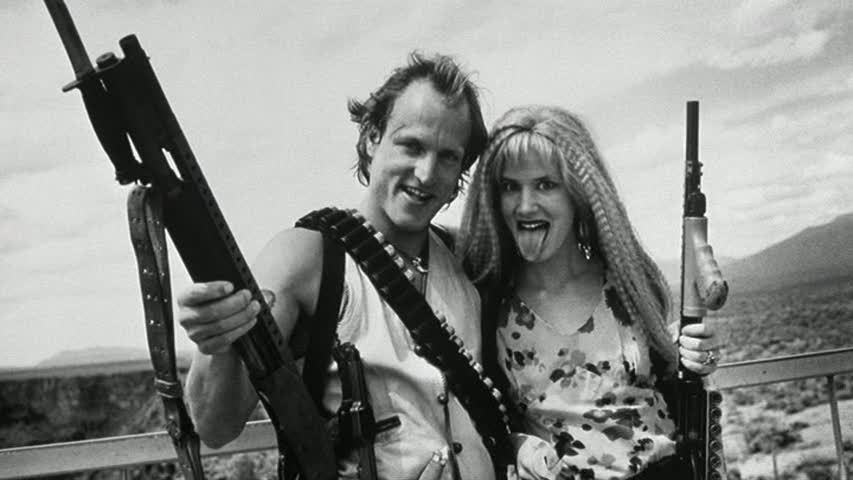

Road Movie: Natural Born Killers (1994) | dir. Oliver Stone

Though there is a broader definition of the genre (i.e. films with road travel), the classic road movie was a unique window into the young American psyche and an interesting modern application of the monomyth. Films like Easy Rider (1969) and Badlands (1973) kick-started the genre, involving heroes that were invariably on the run and unable to settle down, often featuring violence as a result. As Roger Ebert points out, the road movie “is a form which breaks filmmakers free of tight plotting and opens them to whatever happens along the way” – and this looseness becomes evident in the road movies of the ‘80s, where the violence begins to seem more and more like an arbitrary landmark of a dead genre. While the genre wasn’t as dead as, say, the Western, it certainly came to a period of artistic stagnation with little direction after the high point of Thelma & Louise in 1991.

Unlike previous entries in this list, Natural Born Killers is an unapologetically and indulgently violent film. Its over-driven commitment to the senseless violence of the road movie functions as a salient, if controversial, practical commentary on the glorification of violence in the media. The film employs many visual styles ranging from surreal to visceral, an aesthetic that highlights the absurdity of the characters and events while not overlooking the consequences of the characters’ actions – though, unfortunately, the film itself did spawn copycat crimes.

But even if you think the message is handled poorly, it’s worth a look purely for Robert Downey Jr.’s brilliant portrayal of a psychotic Australian journalist. If nothing else, the film’s audacious overdriving of the road movie’s tropes certainly brings life to a great genre that had become formulaic and irrelevant.

For more Lists, click here. If you’re digging ReelGood, sign up to our mailing list for exclusive content, early reviews and chances to win big!