Turing the world.

The Imitation Game is a film about intelligent people for stupid people, thanks to its astonishingly illiterate approach to a complex process. Alan Turing, the subject of Morten Tyldum’s new film, was a British mathematician, cryptanalyst and computer scientist, largely responsible for breaking encrypted Nazi codes during World War 2 – work which would prove monumentally important for Allied victory. Winston Churchill himself once said that Turing made the single biggest contribution to German defeat during the War. His work deciphering Enigma, the infamous German encryption device, is surely fascinating and yet The Imitation Game offers no insight into how Enigma works and no insight into Turing’s process, preferring instead to unveil Turing’s work through largely fabricated melodrama.

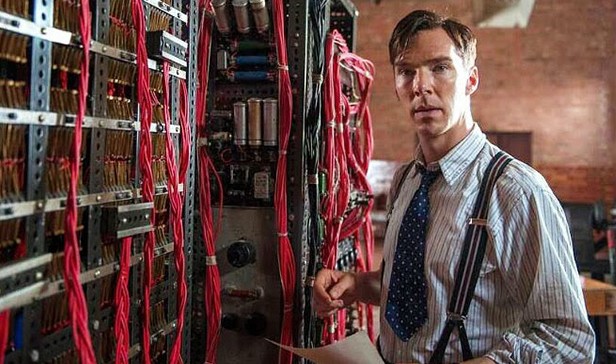

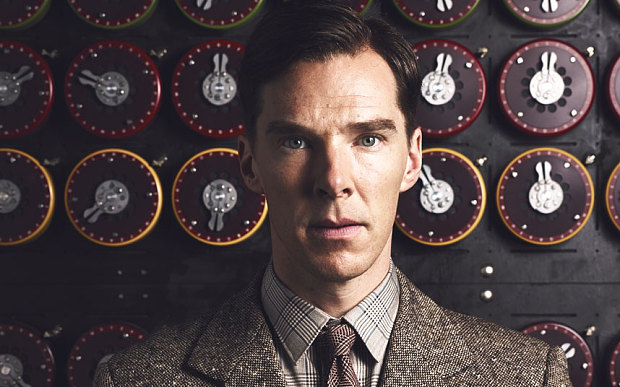

Turing (Benedict Cumberbatch), a young Cambridge graduate with a penchant for crossword puzzles, is welcomed into a top secret government program, the purpose of which is to break Enigma – the machine responsible for encoding all of Germany’s transmissions. Joining a small team at the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park, Turing is initially outcast by his fellow cryptanalysts and his superiors because of his alienating character.

“We’re going to break an unbreakable Nazi code and win the war,” one character quips, just in case the filmmakers hadn’t condescended enough. The line is an outcome of a weak, exposition laden script but it also sums up exactly and entirely what an audience will get out of The Imitation Game. It’s a simple, unexceptional movie about a complex, exceptional machine. The machine in question is called Christopher, after a childhood friend of Turing’s (one of many contrived plot elements – there was no Christopher and indeed the machine was actually called Bombe). The function behind the Enigma machine and the process of how Turing’s machine deciphers it remain a mystery, despite surely being the most appealing element of Turing’s story.

The film suggests that it took a man who didn’t understand basic human communication to break the contrary language of Enigma. Fair enough, although by all accounts Turing, despite certain eccentricities, wasn’t as socially inept at the Tyldum wishes he was. This liberal attitude toward fact saturates The Imitation Game, essentially draining the film of all credibility. What’s an Alan Turing film that isn’t an Alan Turing film? It’s an awful and regrettably frequent consideration of filmmaking that facts be altered for the sake of narrative. Truth is always stranger than fiction, What’s the point of watching a film based on fact that in reality isn’t based on fact. The attempts to heighten tension are painfully conspicuous, and beg the question – why did the filmmakers decide to make The Imitation Game if they weren’t confident in the strength of the material?

The Imitation Game uses Turing’s personal life, his tics and his sexuality – he was a gay man in an era in which homosexuality was illegal – to help define his work in Bletchley Park. Perhaps they were contributing factors in Turing’s motivation but Tyldum doesn’t convey this convincingly. For much of the running time it feels as though the filmmakers are trying to wring a much livelier story out of the whole affair. Turing may have just been doing his job and considering the nature of his employment what’s so uninteresting about that?

The translation of Engima is a natural compelling story and the rare moments in which Tyldum focuses on the code breaking are the highlights of the film, despite being short on any genuine insight. What’s to gain from The Imitation Game? Ironic that the complex work of the team at Bletchley Park is moderated into such a simple film.

4/10

For more Reviews, click here. If you’re digging ReelGood, sign up to our mailing list for exclusive content, early reviews and chances to win big!