Vice squad.

“So, you’re here about…?”

“Good question.”

Inherent Vice is what happens when a meticulous filmmaker allows themselves a creative liberation that doesn’t necessarily befit the sensibilities that usually makes their work successful. There are flashes of brilliance in Paul Thomas Anderson’s film, which is an adaptation of the novel of the same name by the notoriously impenetrable writer Thomas Pynchon. By all accounts it’s a faithful adaptation. It’s not a successful one, perhaps because it’s so faithful to the source material. But there’s also a laziness to the film that belies Anderson’s talent. Fastidiousness saturates the best examples of his filmmaking. By comparison, Inherent Vice feels forced, rushed and careless.

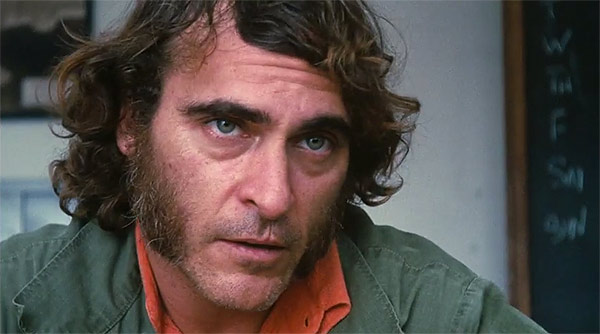

Standing in the shadows of sex, drug and violence-infused noir such as Howard Hawks’ The Big Sleep, Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye and Joel and Ethan Coen’s The Big Lebowski, Anderson’s film pales by comparison, despite clearly finding inspiration in all three. Protagonist Larry ‘Doc’ Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix) occupies a congenial filmic space somewhere between Philip Marlowe and The Dude. Phoenix is wonderful as Doc, who navigates his way through life amidst a haze of smoke and hallucinogens. So it’s no surprise when Doc is surprised one evening by Shasta (Katherine Waterston), a former lover who arrives at his doorstep with a story about a plot to wrongly commit her new lover, real estate tycoon Mickey Wolfmann (Eric Roberts), to an insane asylum.

The crucial difference between Doc and The Dude, who share a devotion to altered states of consciousness and an informal approach to investigation, is that the Dude never really cared about where Bunny Lebowski went. Neither did the audience. Anderson’s film plays on Doc’s enthusiasm for narcotics as a deciding factor in his work as a private detective. Facts, clues, red herrings, coincidences, characters, narrative and purpose are corrupted in a haze of smoke and we’re as lost in the incoherence of it all as Doc. It’s an intentional effect but it’s not a rewarding one. Characters speak in riddles, or maybe Doc just thinks they speak in riddles, but then so do we. Doc shouldn’t care about Pynchon’s narrative, because it’s convoluted and behind the mess it’s not all that interesting. Inherent Vice is a film about character, situation and about Doc’s interaction with his environment that doesn’t fully commit.

The Big Sleep was notoriously baffling but what Hawks’ film lost in clarity it made up for in a fantastic protagonist, an electric sense of atmosphere and moment to moment brilliance. The Big Lebowski used The Big Sleep for inspiration, had a comparable regard for lucid plot and exploited the idea in parody. Both films are self-aware enough to understand that plot isn’t a strength. Inherent Vice suffocates itself with long, exposition-laden monologues that are impossible to follow and difficult to muster much interest in. It’s Pynchon’s story, but it’s Anderson who never offers much incentive to decipher the labyrinthine plot. It’s dense, punctuated by promises that don’t deliver and behind it all is a series of banal plot points. When this sort of film, of which there are many fine examples, work then these complaints shouldn’t be an issue because it’s the experience that’s important, not the skeleton. Brief moments of clarity suggest that if we could comprehend any of what’s going on it wouldn’t be particularly interesting.

Inherent Vice is a deliberate mess that never lives up to the sum of it’s fantastic parts, which include a strong cast, some evocative production design and a thoughtful, ambient score from Jonny Greenwood. Such poor work from Anderson is alarming.

5/10

For more Reviews, click here. If you’re digging ReelGood, sign up to our mailing list for exclusive content, early reviews and chances to win big!