“Saigon….shit, I’m still only in Saigon….Every time I think I’m gonna wake up back in the jungle.”

What new light could really be shed on Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 masterful adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness?Apocalypse Now and its production have become so ingrained in cinematic culture over the years that there seems little left to discuss and even less to ponder. But I’m going to do it anyway.

There are some films that transcend appraisal. Five stars, ten out of ten and two thumbs up do not apply to them. These films are so rare I could count them on one hand, and they vary from person to person. In my opinion, Spike Jonze’s 2002 film Adaptation is one.Apocalypse Now is another. I like to presume that Francis Ford Coppola wakes up every morning, walks to his bathroom mirror and says to himself, “You made Apocalypse Now… you absolute champion.”

“I was going to the worst place in the world and I didn’t even known it yet.”

The 1970s film industry in America was a revolution. The original film school generation was burning through Hollywood; Spielberg’s Jaws (1975), Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976), Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show (1971), De Palma’s Carrie (1976) and of course Lucas’Star Wars (1977) had all been released and were met with phenomenal success. But arguably no accomplishment in 1970s filmmaking rivals that of Coppola’s. He made no less than four masterpieces over the decade, including the first two parts of The Godfathertrilogy (1972/74/1990), concluding the trend with Apocalypse Now.

Adding to his legend, the director has never come close to reaching the same heights again. His best films since his venture up the river have not been much more than competent filmmaking.

“Hey, you know that last tab of acid I was saving? I dropped it.”

Those who have read Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness as well as seen Coppola’s film will immediately notice the differences between the two. The most noticeable of course is the setting, but there are a number of other important departures from Conrad’s story, such as Willard’s (Marlow in the book) murderous intent from the outset of the journey. Instead of a blindly faithful adaptation of the novella, Coppola has managed to create a completely separate companion piece. That one is rarely mentioned without reference to the other is a testament to how relevant to the source material Coppola still managed to keep his film.

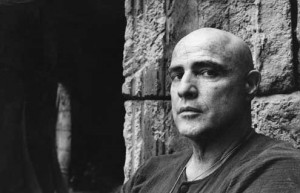

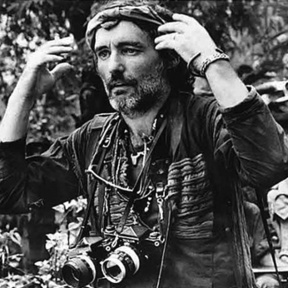

There is a fantastic documentary I’m sure many of you would have heard of called Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse (1991) detailing the troubled shoot, using documentary footage captured by Coppola’s wife Eleanor. But even before the documentary was released, the shoot was stuff of legend. Harvey Keitel had originally been cast as Willard only to be fired a few days into production. His replacement, Martin Sheen suffered a near-fatal heart attack on set. A devastating typhoon destroyed the sets at Iba, shutting production down indefinitely. Most of the cast was on a cocktail of drugs, including strong hallucinogens, for much of the shoot. Top billed Marlon Brando arrived on set immensely overweight, with a shaved head and no prior knowledge of Conrad’s book.

It may also be the stroke of genius of taking Conrad’s novella and setting it in the Vietnam War, so soon after the fall of Saigon on April 30th, 1975.

Apocalypse Now is an anti-war film, but not in traditional fashion. There is no sense of humanity in the reels of Coppola’s film, we never truly feel anything for the bloodshed on screen. Perhaps therein lies Coppola and Conrad’s point. In Conrad’s story, the further upriver Marlow went, the deeper and darker he delved into his own mind. Kurtz is insane. As Willard/Marlow pushes on down the river he begins to empathize with Kurtz’s ideals, losing faith in ordered civilization. Coppola points out that war is the final destination.

“We must kill them. We must incinerate them. Pig after pig… cow after cow… village after village… army after army…”

There is something working for Apocalypse Now that is indefinable, impossible to identify. Perhaps it is art imitating life at its most startling. Just as Willard manages to obtain a small semblance of closure in the darkness of the Kurtz’s camp, Coppola was able to somehow create cohesion from chaos.

“I watched a snail crawl along the edge of a straight razor. That’s my dream; that’s my nightmare. Crawling, slithering, along the edge of a straight razor… and surviving.”

If you’re digging ReelGood, sign up to our mailing list for exclusive content, early reviews and chances to win big!