In vogue.

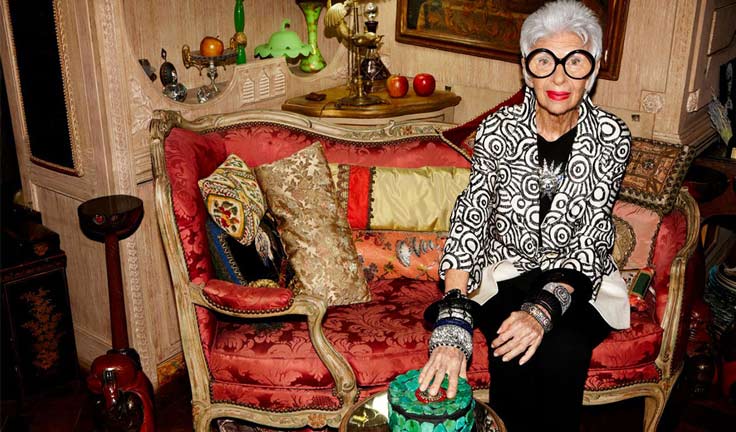

When Iris Apfel was a young women, she was taken aside by fashion legend Frieda Loehmann and told, ‘You’re not pretty and you’ll never be pretty, but it doesn’t matter. You have something much better. You have style.’ Apfel is now 93 years old, a fashion institution in her own right and the subject of the new documentary by Albert Maysles, Iris. Maysles, along with his late brother David, is most often associated with the documentary style called ‘Direct Cinema’, which is perhaps best characterised by an absolute drive to represent and question reality in documentary. Together, the brothers are responsible for significant works such as Gimme Shelter and Grey Gardens, before David’s death in 1987 ended their filmic partnership. Albert himself died in March this year, not long after completing Iris.

Maysles once commented that “as a documentarian you are an observer, an author but not a director, a discoverer, not a controller.” In Iris, his camera regards Apfel without remark or review. The film is Apfel’s character, not Maysles’ camera. Maysles is confident enough in his choice of subject to just witness. Apfel’s personality is enough comment on her personality.

The purpose of the fashion industry is inherently ambiguous. There are clothes, such as the ones worn by humble film reviewers. Then there is fashion, dictated to us by the social elite. Then there is fashion as art. Apfel engages perhaps most apparently in the latter, or rather she is engaged with. In 2005, The Costume Institute, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, launched an exhibition focusing on Apfel’s style entitled ‘Rara Avis (Rare Bird): The Irreverent Iris Apfel’, prompting surge in awareness of Apfel and her work. She enjoys the attention, but there’s the distinct sense that Apfel is entirely motivation by a love of what she does and a love of what she loves rather than any need for professional or personal validation.

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder and Iris is a celebration of individualism. “I don’t have any rules,” Apfel comments, “because I’d only be breaking them all the time.” She finds bracelets in bargain bins and hats in thrift shops. Her style is wholly unique to her. It’s what appeals to her not what correlates to the current fashion movement. She bemoans the uniform tendencies of the greater fashion world.

Maysles catches her gently bickering with her loving husband Carl about who ate the yoghurt in the fridge. It’s a moment as far removed from the arena of high fashion as anything. Apfel didn’t find the world of fashion; it found her. It’s not fashion that keeps her up at night, she says, it’s issues like health. Her mother treated accessorising like a religion, she admits. But Apfel is devoted to fashion and style, not consumed by it. “I can’t sit in judgment,” she says. “If they’re happy that way…it’s better to be happy than well dressed.”

You might need to be a fashion enthusiast to understand what makes Apfel’s work so significant but the language of devotion is universal. Maysles’ film is a wonderful testament to the unbridled love of a pursuit. That it is fashion, an industry often associated with pompous and hollow sentiment, in question just reinforces what makes Apfel’s passion so refreshing. If you love something, whether it be clothes, design, sport, film, literature or any calling of passion, it shouldn’t matter what other people think. That the fashion world is so interested in Apfel’s work is a happy byproduct.

7/10

For more Reviews, click here. If you’re digging ReelGood, sign up to our mailing list for exclusive content, early reviews and chances to win big!