The trouble with The Trouble With Being Born is that for all its arthouse ambitions toward examining the moral, ethical and existential byproducts of artificial intelligence, it has its roots in better films. One shouldn’t suggest Steven Spielberg made the definitive film on A.I. when he finished Stanley Kubrick’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence, especially since that film is 20 years old, and has its flaws. But images of a hopelessly loyal artificial child, discarded by those who were supposed to love him, may never get more indelible than that look of frozen optimism on Haley Joel Osment’s face.

On the arthouse side, The Trouble With Being Born also has a clear line of ancestry. It’s not possible to watch Sandra Wollner’s German-language film without being reminded of Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin. Under the Skin does not concern a form of artificial intelligence, but it does feature an alien life form – literally alien in that case – trying to practise its interactions with humans so they present as normal. Both films even begin with the sounds of linguistic gobble-dee-gook, as though the entity in question is participating in a language-based synchronisation while coming online. (In fact, A.I.’s David also “pairs” to his human mother by repeating a particular sequence of otherwise unrelated words.)

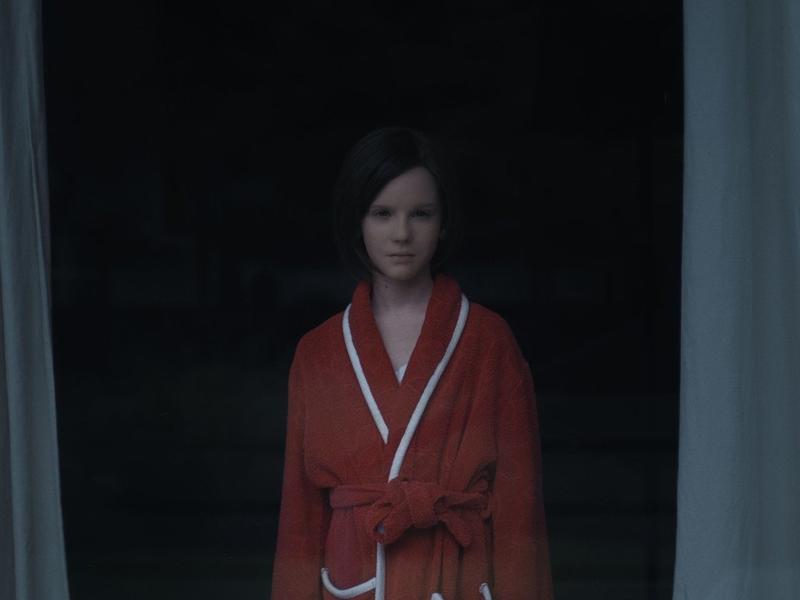

“Pairing” has a literal meaning in The Trouble With Being Born. We first meet Elli (Lena Watson) in the guise of a ten-year-old girl living with a man in their idyllic summer home with its sparkling swimming pool. A few minutes later, she’s floating face down in that pool, but the man, Georg (Dominik Warta), treats this development with the sort of detached frustration of having left his mobile phone out in the rain. That’s because Elli is similarly a mechanical device, and though she’s short-circuiting at the moment, Georg is able to bring her back online with an instruction manual and the push of a few buttons. We even hear “Pairing … pairing … connected,” as should be familiar to anyone who has ever used Bluetooth ear buds. Elli’s head snaps to attention and she’s back in the game.

Elli does not have to be a she. She’s whatever her owner wants, or needs, her to be, customisable in face and body. (We learn this last part during a scene of routine maintenance, when Elli is as naked as the day she was manufactured, and there’s an empty socket where her genitalia should be.) In the case of Georg, she appears to resemble a child he once had, or maybe a girl he loved when he himself was that age – it isn’t entirely clear. We do know that it’s heavily suggested their relationship might be something other than parent-child.

The controversy this film courts would be a lot more worthwhile if Wollner did more with the story. It’s by design that the story is presented in fragmented form, individual moments of prolonged ennui, rather than a point A to B to C narrative. And that can be a very effective means of telling a story. The languorous pace, though, starts to inhibit your ability to stay focused, and worse, your ability to care about the characters.

As for that controversy, which of course was inflamed mostly by people who have not yet seen the film (which is most people, as it has only played festivals thus far), there are some, shall we say, squidgy moments. If you are suggesting a paedophilic relationship between a man and a younger child, there are limits to what you can actually show so as not to implicate the actors in something immoral and illegal. Wollner’s suggestions are enough, though, and she’s got some clever techniques for presenting them. For one, any nude shot of Watson uses CGI. Then there’s a shot where the two are in the pool, and you’re seeing him from behind, while she is almost fully eclipsed by him. You can’t know how close their faces are; you can only imagine.

But imagine to what end? It’s not clear why a film that wants to tackle issues related to the emotional lives of machines also needs to throw in paedophilia, unless to distinguish it from the aforementioned films to which it is most readily comparable. It’s disquieting to consider the nefarious ends a user, in all senses of that word, would pursue with a machine that only resembles a child, when perhaps there would be no punishment associated with those transgressions because the child is not really human. That would be one avenue to go down, but The Trouble With Being Born kind of leaves that thread flailing.

It’s a shame there is not better focus in the film’s overall thrust, because the mood it creates can be quite effective, if a little absent. Wollner is spot on with her camera setups, as she wanders through this house and the surrounding forest, creating a kind of out-of-time dreaminess. You couldn’t find a more unnerving young actor to play Elli than Watson, who has some plastic prostheses to complement the expressionless stares she produces on her own. When her lips are closed, they appear like putty with a crease carved into it where the lips should part.

When a film does as much right as The Trouble With Being Born does, it seems like it should earn a higher rating than I’m giving it. But however many ways you parse its individual ingredients and appraise their relative strengths, and even setting aside its controversies, the end result is that this is a 94-minute slog. It never gathers the momentum to really make its ideas sing, and then kneecaps them further with a structural switch at the mid-point that resets some of the story elements. That’s a frustrating development in a story that was already struggling to find its way.

The Troule With Being Born is currently playing in cinemas.