Uncovering Snowden.

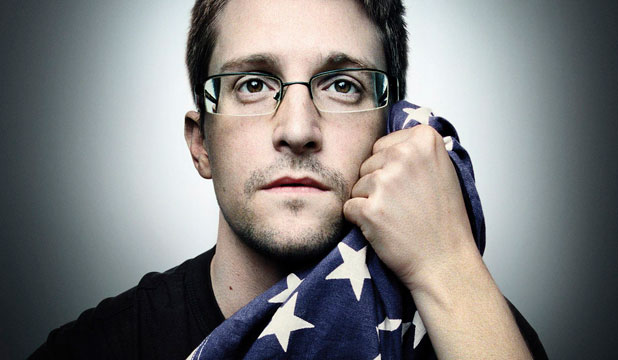

When American filmmaker Laura Poitras made the first of her three films that would explore post 9/11 America, she probably didn’t anticipate the third and final, Citizenfour, would involve her having near exclusive access to the man who would provide one of the biggest leaks of government documents in U.S history, the same man who would be the centre of one of the new decades biggest stories; Edward Snowden.

The way in which Poitras treats this insider access is admirable, the film never trumpeting itself in the way a current affair or news program might do if they had similar access to a similar figure. And though it sounds contradictory, it’s a film that’s not self important, but well aware of the importance of the message within.

This is because Poitras never blows her own horn, the director deliberately keeping herself off screen for the films duration. Apart a glimpse or two in the reflection of a mirror, her presence comes only in the form of her voice reading the occasional transcript of communications with Snowden or her written word on screen to help link the gaps in time between footage.

Poitras knows that this is about Snowden and more broadly, the issues he is bringing attention to: that the National Security Agency have powerful technology that can intercept a mind boggling amount of telecommunications per second, and that there is a distinct lack of red tape to prevent them from tracking individuals that don’t pose an immediate threat to security. Making the film less about the filmmaker is sensible yes, but it does also work to the films disadvantage at times: Poitras could perhaps afford to use herself more as an example of how the NSA use their communication intercepts to unjustly track journalists and filmmakers, not just terrorists. As Snowden and the film suggest, the NSA’s actions have broadened the definition of what can be done in the name of national security, to scarily invasive lengths.

The lack of bells and whistles in Poitras’ film might draw the ire of some, but the plaudits of others; one could easily imagine any other filmmaker using flashy graphics to explain exactly what the NSA are up to and how their systems work, instead we rely on Snowden’s verbal explanation. Another director might dramatise conversations had with their subject; instead the minimalistic Poitras gives us typed text on the screen. Even the cinematography is effective in it simplicity; wide still shots on an unmoving tripod help convey different ideas throughout the film, be it the silently intrusive reach of the NSA, or Snowden’s isolation as he holes up in a Hong Kong Hotel.

Less calculated hand-held footage meanwhile subtly shows Snowden’s deterioration. Where he starts out comfortable in his convictions, seemingly prepared for the storm ahead, the bags under his eyes and the blemishes on his skin that develop as the leaks unfold say a lot about the pressure he finds himself under.

Ultimately the film feels unbalanced, not in terms of its integrity but purely in the sense three quarters of the film follows Snowden so closely, yet the last stanza (due to both he and Poitra’s departing Hong Kong) doesn’t feature him at all, Poitras attempting to fill this gap by half heartedly following the leaks impact in a couple of newsrooms in the U.K and Brazil.

But it’s in line with a film that is largely understated in its delivery; revelations aren’t accompanied by music nor followed by dramatic silences, instead the cumulative weight of the information, the realisation of what kind of world we’re living in and what kind of world we’re heading towards, slowly builds on the viewer as you approach an ending that is scarily without any real resolution. Citizenfour is not a perfect film, but it’s possibly one of the most important documentaries you’re ever likely to see.

8/10

For more Reviews, click here. If you’re digging ReelGood, sign up to our mailing list for exclusive content, early reviews and chances to win big!