A quick glance over the trivia portion of M. Night Shyamalan’s IMDb page, admittedly not an airtight source of factual accuracy, suggests that the man is an avid comic book reader. Shyamalan’s latest film, Glass, ostensibly a film that intends on engaging with and deconstructing the comic book medium, indicates otherwise.

Glass is occupied with characters who comment on the action and narrative as though they were elements of a constructed comic book. Though my own grasp of comic culture is limited, but not absent, I was acutely aware during my watching of Glass that what these characters say on the subject simply does not reflect that culture accurately. It’s only a significant problem because Shyamalan pivots his entire film around this concept.

In one instance, a comic book shop is divided into “Heroes” and “Villains” sections, bringing up a whole series of questions regarding what sort of chaos such a system engenders. In another instance, Shyamalan simply fabricates the concept and purpose of “limited edition” comics. The impression that Glass leaves is that we are being lectured on a topic by someone who plainly does not know it.

The film is a sequel to Unbreakable, a wonderful movie made before Shyamalan’s all but inexplicable descent into filmmaking purgatory, and Split, Shyamalan’s previous film, which many heralded as a return of form for the director. It wasn’t, but certainly demonstrated a greater awareness of what constitutes acceptable levels of quality cinema than has been demonstrated by Shyamalan for years.

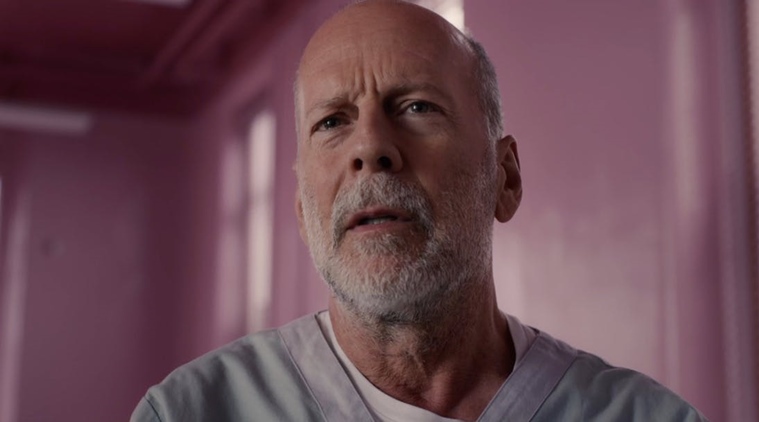

James McAvoy‘s performances is undoubtedly admirable though the collection of characters he plays, living collectively in the body of Kevin Wendell Crumb, provides a more sensational consideration of Shyamalan’s ultimate intentions than those intentions deserve. David Dunn’s condition, his invulnerability, remains a – relatively – persuasive possibility in the film’s world of conceivable superheroes.

We are reintroduced to both characters at the outset of this sequel, set nineteen years after the events of Unbreakable and three weeks after Split. David Dunn is operating as a vigilante, using a security systems business as a front, with the help of his son, Joseph (Spencer Treat Clark). His efforts lead him to the whereabouts of Crumb, still advancing his crusade against the impure via the kidnapping of teenage girls.

Their confrontation eventuates in the capture of both men by authorities, the police viewing Dunn and Crumb as lunatics labouring under delusions that they are comic book characters. This is the first indication that Shyamalan’s execution isn’t capable of supporting his concept. Sarah Paulson‘s Doctor Ellie Staple claims to be a specialist in such a condition, but expresses it in such an underwhelming manner that this central element of the film never overcomes its implausibility. One of the many strengths of Unbreakable is its sense of plausible, even when concerning itself with the farfetched.

Also contained to the mental institution in which Dunn and Crumb are being held is Samuel L. Jackson‘s Elijah Price, whom fans of Unbreakable will undoubtedly remember fondly. As in that film, Glass’ preoccupation with the idiosyncrasies of comic books is fundamental to the narrative of Glass. Unlike Unbreakable, that preoccupation is a narrative weakness, rather than a strength.

Suspension of disbelief is a powerful, and fun, tool when it comes to enjoying films. Glass curtails our ability to engage in such a suspension by positioning its sensational characters in a situation characterised by reality. Adversely, it is imbued with countless examples of improbability, such as the astonishing condition of security at the mental institution, that are difficult to accept because of our diminished capacity to suspend disbelief.

Shyamalan bashing isn’t very fun anymore, a consequence of its exhaustion over the past almost twenty years. It is nonetheless disheartening to process such a decline in talent from a filmmaker responsible for two vigorously good films. Glass is absolutely not Shyamalan’s worst film, though it is another telling indication that he may never again come close to his best.